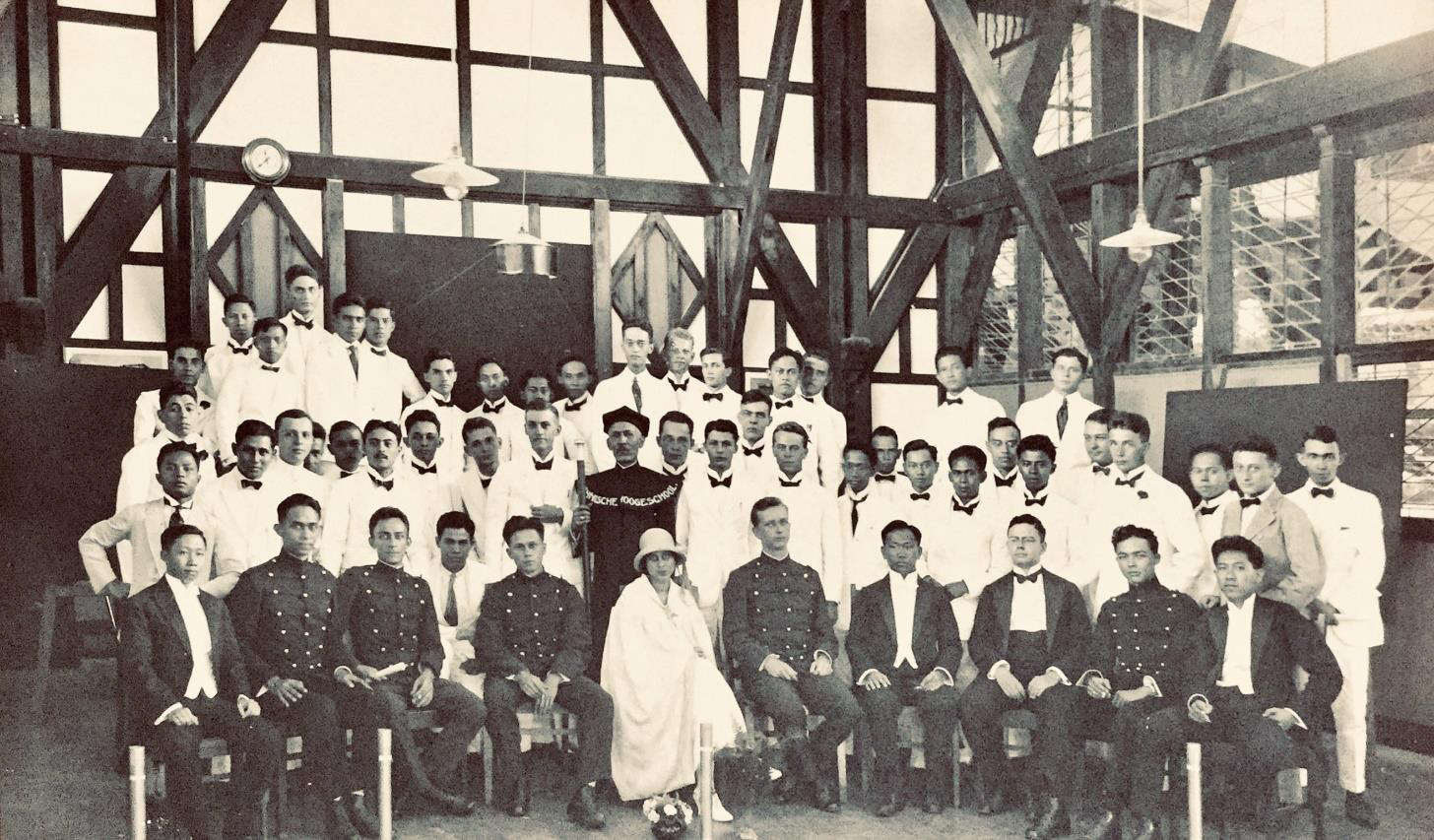

The first woman engineer in Bandung

‘That woman was my grandma’, wrote a reader in response to the article on 100 years of the Bandung Institute of Technology (Delft Outlook, July). Who was this woman in the first cohort of civil engineering students in the former Dutch East Indies? Granddaughter Annette Lievaart tells the story of her grandmother Lies Odenthal.

Her name was Elisabeth Antoinette Odenthal (Lies to her friends). She was born on 27 April 1902 in Surabaya and died on 16 January 1984 in Roosendaal. My grandma was born and raised in the Dutch East Indies, where her forefathers had lived for many generations. She was a Dutch national and clearly had Indonesian heritage. Encouraged by her parents, she decided to study civil engineering in Bandung. She would rather have studied mathematics, she told me later, but that wasn't possible in the Dutch East Indies and she certainly didn't want to travel to the distant Netherlands.

My grandpa – Adolf Petrus Frederik Kist – also started in the first cohort. As my grandma finished studying a year before my grandpa, she took a job as a science teacher at a convent school in Bandung. They were married in Surakarta on 22 May 1926. My grandpa was already working as an engineer for the Provincial Public Works Department in Bandung and my grandma was a housewife, as was usual back then. The family story goes that if my grandpa had to calculate a new project, he took it home for my grandma to help him.

Right at the start of World War II my grandpa was interned as he was a reserve officer, leaving my grandma to care for three children. She went to live in a house together with a second cousin and all the children. The cousin gave singing lessons, which was not allowed, but according to my grandma, the Japanese were so charmed that they allowed her to continue. As there was already so much coming and going in the house, my grandma decided to give private maths lessons. The schools and university were already closed and what she was doing was forbidden, but her students blended in with all the music students. This enabled her to earn something of a living, even though she did it more on principle than for the money. She also refused to bow to the Japanese she met on the street.

After the war, they tried to pick up the pieces of their lives. Despite the start of the military actions, my grandpa became head of the Java district Public Works Department. In 1948 he was also appointed extraordinary lector in road construction at the ITB. In 1949 he was able to take leave and travel to the Netherlands. On 26 July 1949 they set sail on the Willem Ruys and arrived in Rotterdam on 15 August. My grandparents planned to get my aunts settled and then return to the Dutch East Indies with my mother. Unfortunately, they were forced to change their plans as the transfer of sovereignty took place while they were in the Netherlands and a return to Indonesia was no longer an option. Even though my grandpa worked for the Dutch government all those years, he was now unemployed and left to sort things out for himself. One of my aunts said this was partly because my grandparents knew President Sukarno from their student days and Sukarno even fancied my grandma a little. People from my grandpa's circle explicitly asked him to return to his old position, in which case the family would be given Indonesian nationality. My grandpa turned down the offer.

He eventually found work in the Water Cycle Laboratory in Delft and taught at the Institute of Technology, specialising in Road Technology. In 1955 he took up a post teaching Civil Engineering at the Royal Military Academy in Breda. Here he trained Military Engineering cadets and founded the Military Engineering Laboratory. He worked in Breda until his retirement. The desire to teach continued, and for the remainder of their lives my grandparents helped the neighbourhood children with their science homework. When I took my pre-university school-leaving exams, my grandma was very interested in the maths and physics assignments, although less impressed by probability theory and statistics. Fortunately she was still around to see me enrolled as an Applied Mathematics student in Delft, and to see I had a boyfriend who also studied in Delft. Now we've been married nearly 30 years and we are both engineers. In November 2019 our eldest child graduated in Aerospace Engineering. For this occasion we instituted a tradition that our children should be given a book from my grandparent's collection of textbooks. But I'm keeping the lecture notes on integral and differential calculus and geometry by Boomstra for myself.

By the way, I saw my grandma mentioned in a biography on Sukarno by Lambert Giebels (Sukarno: a Biography). My grandma said that Sukarno received equal treatment as a student until he began his propaganda campaign for independence in earnest. That he never forgot my grandma can be seen from when he was introduced to a cousin of my mother who looked a lot like my grandma, and he said: “Lies, is that you?”. When my grandma heard this she said: “Did that nutcase think I stayed forever young!”

Two mini-exhibitions, on Delft Civil Engineers in the Dutch East Indies and Architecture in Bandung, can be seen in the hall of the TU Delft Library until March. From the start of 2020 they can also be seen online at erfgoed.tudelft.nl.