How undertows are threatening dikes

The nightmare of every dike reeve. One week of high water and a river dike suddenly subsides and breaks its banks. How can this happen so suddenly? Engineering PhD candidate Joost Pol investigated how undertows – or ‘piping’ – under dikes arises and how it can grow from a phenomenon of a few millimetres into a potential catastrophe.

A clay dike may look solid, but if it rests on a sandy bottom and the water rises, the water pressure beneath the dike rises too. A small fissure in the clay can be the start of a major leak. This occurrence is visible on the inside of the dike, deep in the polder, as a mound of sand that swells up from the soil.

Experts talk about piping as a feared failure mechanism of river dikes. What starts as a tiny eddy can grow into a raging current that undermines the dike and causes exponentially more rapid erosion. Sand washes away and the dike subsides. That much is known. But how fast is the process and what conditions is it dependent on?

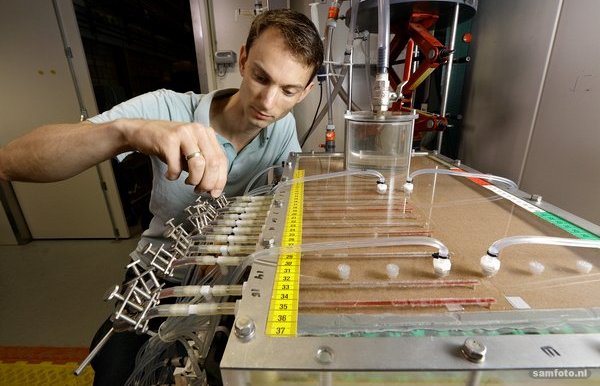

In Deltares’ geotechnology laboratory, Joost Pol is simulating the piping process in a layer of sand under a perspex plate. A row of tubes is measuring the local pressure and a camera above the structure is recording the test. He sees channels of a few centimetres wide and a few millimetres deep emerge that grow about half a metre per hour.

When a small flow that starts out completely under the dike has expanded to the river, the process suddenly speeds up as the water can flow freely.

Halfway through his doctoral degree, Pol determined that the speed in which the fissure grows depends on the properties of the sand and current. He summarises his findings by saying “In short, the growth rate increases according to the size of the sand grains and the subsidence rate is then higher”.

Pol is still working on a numerical model that simulates the piping process. This will allow him to draw on his research results in running risk analyses of dikes. Previous assessments have shown that three quarters of river dikes have piping problems. The research results will help will help identify where dike reinforcement is needed.’