A robot friend for ill children

What are the challenges?

1. Having a conversation with a robot

“The idea is that a child meets the robot friend when they arrive at the hospital. This allows the robot to learn about the child. The relationship can be further developed in various contexts (such as in the playroom, bedroom or treatment room), and the child can decide whether to take the robot friend with them.

Dialogue with a robot is truly ground-breaking. Generic conversation is not possible, so it is about very specific types of dialogue. It starts with the introduction, which already presents a challenge to a robot. What should he ask, and how should he respond to the child’s answer? This is not something that I can just pull off the shelf; there is no rulebook that says ‘you should do it like this’. One of the things that I really enjoy about this project is that we learn an awful lot about people.

The robot is like a mirror. We first have to establish how people act during introductions, then make a working robot version of that. The same applies to conversations about what you have experienced. How do we do that? Well, we have to comprehend it, and then create a robot version.

That is why we work with contexts. The playroom presents scope for fun; what would the child enjoy: a game, a story, or a chat? In the bedroom, a child may not be able to sleep and the robot can assume the role of a coach. We do not have to start from scratch. We have a basic architecture to control the robot, and a cognitive language.

But the big question relates to establishing how a robot can conduct a conversation, what the dialogue precisely consists of and how ‘pre-programmed’ everything is. Of course, I hope we will be able to initiate highly amusing and natural-seeming conversations in which the child takes the lead, but I think we might end up occupying the middle ground.”

2. Giving a robot a cognitive memory

“So what we actually do is fitting a robot with mini conversations, making it more fun for a child to be with the robot and, in turn, allowing the robot to recall information about the child. That’s why it is important that the robot has a cognitive memory. The striking things are what makes a relationship personal, and which need to come up again later.

If a child likes dinosaurs, the robot can tell a story about dinosaurs the next time they meet. And if the child is too old for a memory game with farm animals, the robot will not suggest playing it. I have spent years working on a cognitive agent programming language that makes it possible to carry out high-level programming of what you believe and what your objectives are; for example, ‘I would like to play a game’. We can explicitly represent these concepts in a learning system such as OWL. What does a robot need to know about a child, about a game, what information do you want to store and what will you use this information for? Well, this language already has the right level of abstraction. It is not low level programming, but we add fundamental cognitive skills, albeit in the robot version. A memory that works like our own memory, in a comparable context. A computer memory is suitable for storing patient data, but does not offer sufficient support for interaction with people.”

“And then you find yourself at the AMC or PMC oncology department, and you see what children are going through. It really hits you, it’s intense. Several aspects of this project make it even more emotive than all the other projects we have done involving the robot and children”.

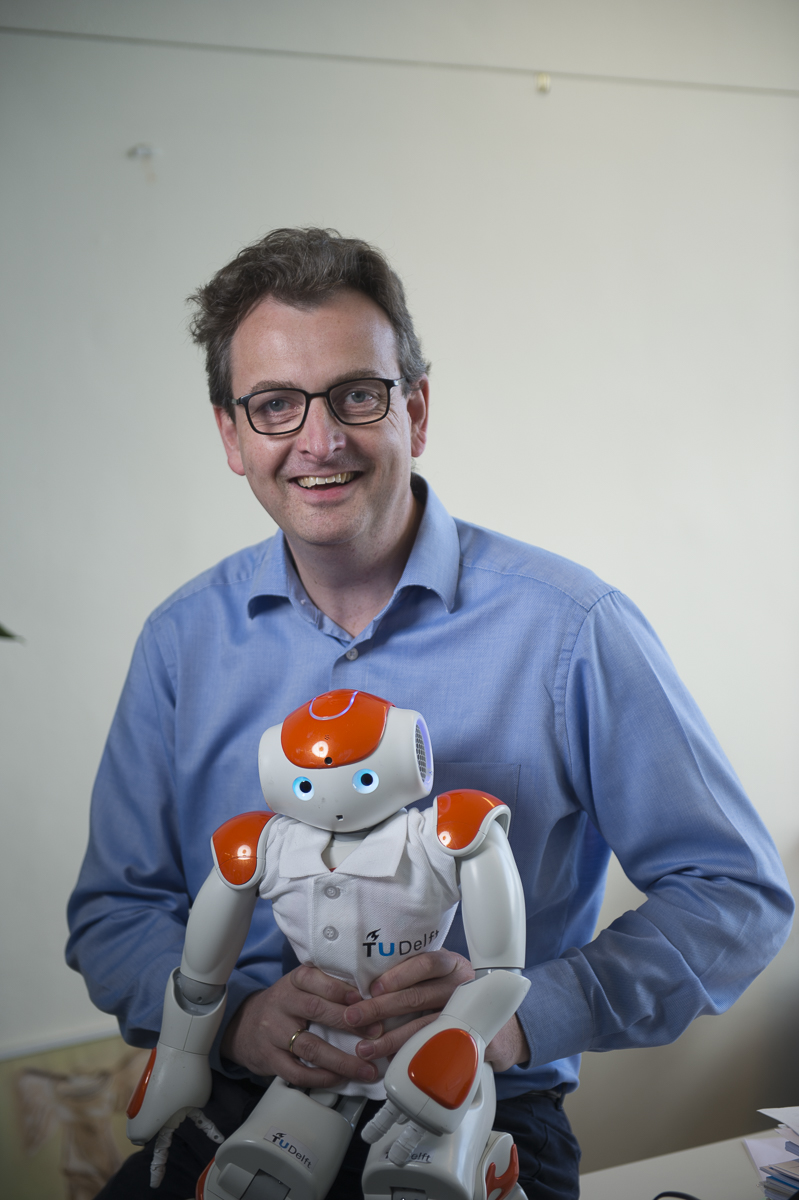

Together with his team, Koen Hindriks is working on a new robot friend: a mechanical buddy for children who need to stay in the oncology department of a hospital. Koen also developed a robot that playfully teaches diabetic children about a healthy lifestyle. Better known as the PAL project, the initiative is still running. His new project is focused on alleviating the stress experienced by children who frequently have to visit (or stay) in a hospital. Children are often scared, and you want as little of that fear to stay with them once they are discharged. All too often, they take it home with them. In this context, a robot is unique as it can go places where people cannot. It was this very context that inspired the project. During a PET/CT scan, a robot can offer welcome distraction by reading a story. And in a radiotherapy room, where the child is not required to lie completely still, the robot is there with them, which creates scope for interaction. A robot can offer additional information about the treatment, or put the child at ease. Facilitating this valuable interaction is the most significant scientific challenge facing Koen Hindriks: being able to have a conversation with a robot, and to instil the robot with empathic capabilities. Koen himself likes to speak in terms of challenges. He is facing a total of seven. Addressing them all will be quite an undertaking, and definitely no sin.

3. Instilling a robot with empathy

“The scientific challenge lies in the interaction, but also in the detection of a frame of mind in a certain context. The Dutch Centre for Mathematics and Computer Science (CWI) is tackling a second major challenge: how can a robot gather the correct state of mind from a child and its surroundings? This is difficult during a PET/CT scan, but the radiotherapy room offers greater possibilities – you could install cameras that transmit images of the child, and of what is happening, to the robot. Detecting emotions is therefore an important objective, as it is something to which the robot can respond. The CWI uses machine learning to identify emotions from faces, or based on sound. A robot itself only has a limited number of sensors, so we install additional sensors in the bedroom or radiotherapy room.”

4. Forgiving the robot’s limitations

“Children are capable of holding deep discussions, but it is ‘only’ a robot, and expectations should be as such. A robot friend is also not meant to replace a human friend; that is not something we want to get into. It is essentially an interactive cuddly toy that helps a child to feel at home. We are very keen to make headway regarding the specific mini dialogues.

They should not feel ‘weird’. A child should not become confused or think that it is doing something wrong. The dialogues must progress naturally, but should also be simple enough for the robot to keep track of. We also need to pay careful attention to the context. A member of staff with pedagogical training will be present in the playroom, and in the bedroom, a robot could alert the parents if human interaction is necessary.

There are still a lot of unanswered questions. How will children indicate what they want? And how can we automatically respond? And also teach the child that they are dealing with a robot? It is a voyage of discovery for us, but also for the child.”

Children are capable of holding deep discussions, but it is ‘only’ a robot, and expectations should be as such.

5. Giving a robot knowledge

“We import a database of stories into the robot. That appears like an easy task, but we have to properly consider the selection. How large should the database be? If you only have five stories, they will all have been told in no time. But if it is 1,000, we would have to spend the entire project enabling the robot to tell the stories.

How often do children like to hear a story told by a robot? I am not sure. It also varies per child. And that is the element of personalisation that the robot needs to be able to respond to. The games are also a challenge. We have already had a lot of success with artificial intelligence. Playing chess against a computer has lost a lot of its appeal, because it is impossible to win. You want a child to enjoy the game, and learn from it.

In earlier research, we looked at responses to a robot focused on winning – and that cheers when it does so – compared to a robot that offers hints. There was a clear preference for the second robot. When an adult is playing a game with a child, it is not about winning, but about the relationship. We need to find a natural balance between the robot and the child winning. And we need to avoid packing too much into the robot. The focus of the project is on the dialogue. That is the scientific challenge.”

6. Becoming friends with a robot

“We have seen that nearly everyone enjoys their first encounter with a robot. After all, it is a totally new experience. Even adults are hugely impressed by a robot that starts dancing or plays air guitar. The second meeting is still quite fun, but you already see the ‘game over’ effect at the third encounter, due to the limited interaction potential of existing robots. And that is not an option in this project.

A child has to spend a fair while on such a ward, and you do not want them to already have lost interest after the second day. Then the child and the robot will definitely not form a relationship. We are yet to establish where the robot will have the greatest impact. The PET/CT scan is the starting point of our project, but we certainly also want to work in the other contexts. The robot and the child are more likely to become friends in situations that are less worrying.

That is why the introduction is also so important in our project. You cannot just send the robot into a treatment room, it would be too disconcerting. And it should not be disconcerting, it needs to be fun. You don’t just plonk a child on a pony; the child first has to get to know the ‘strange animal’ and understand ‘how it works’. It is only then that enjoyable interactions are given a chance. And the child naturally has to think that it is cool.”

7. Introducing the robot to the real world

“We can already demonstrate promising results, but the project is not ready to be brought into use. That is our greatest non-scientific challenge. The architecture is not yet sufficiently stable: from the Wi-Fi through to the dialogue. Certain parts work fine, until another child turns up. There is no manual for humans, but we do need to introduce a fair amount of structure to the robot.

We need to find the correct balance. We also need to remember that it is a robot, and that is fine. It means a certain distance is maintained. People are inclined to be more honest towards a robot. Perhaps because the robot can do less with the information it receives? In any case, we enjoy seeing how the robot and human interact.

Hopefully the parents will also be happy that their child has made friends with a robot. And there is another practical challenge: developing a robot that I don’t have to accompany all the time. A robot with a simple protocol to turn it on and off. It also needs to be sturdy and, to stick with the theme, that is quite a challenge.

We need to quickly get the stories sorted, they can be introduced directly to the children. Our project has a certain structure: the introduction is the second item on our to-do list. We will then move onto the playroom. We did not come up with the concept of a ‘robot friend’, but if we can allow a robot to converse and instil it with empathic capacity in this context, it will be a major breakthrough.”

Text: Marieke Roggeveen | Photography: Marcel Krijger | December 2016

Friends of the robot

¹ STW is part of the Netherlands Organisation for Scientific Research (NWO) and is funded by the Ministry of Economic Affairs. |