The Earth's youngest animal species

Building on evolution

|

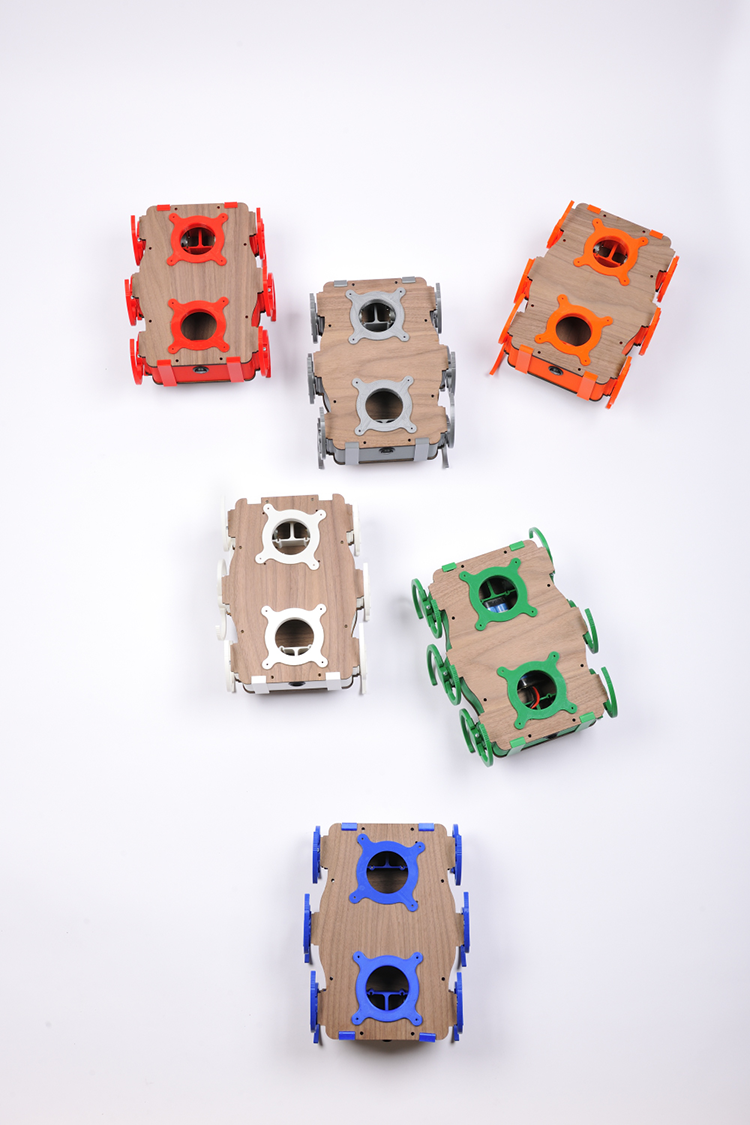

Zebro-project

The Zebro project is a unique collaboration between TU Delft, several universities of applied sciences and the ROC Mondriaan College. Around 60 permanent staff, doctoral candidates and students are working together to develop the latest robots.Strength in numbers

The idea of the robots of the future may bring to mind a robot butler or robots hard at work in a factory. But Verhoeven has different plans for his robots. ‘I am primarily thinking of insect-like sensor robots that can take measurements independently. They will monitor processes and map the world’, he says. Activities could include finding leaky pipes in a factory, detecting weeds in fields, locating a hiker lost in a labyrinthine cave or taking weather readings. Verhoeven expects the robots to make a major contribution to the future Internet of Things: a world in which virtually every device is connected to the internet and measurements are taken everywhere. ‘Installing sensors manually is impractical in that situation”, he says. ‘It means also having to replace broken sensors manually, which is not practical if there are billions of them. It makes more sense to stick the sensors on robots that can then disperse.’

In other words, the robots will not be working alone but in a group, or swarm. To explore a cave system, you send in a swarm of drones that disperse independently. ‘If you programme them not to fly too close to each other, but to remain in contact, a swarm emerges of its own accord that can make its way through the most complex system of caves like a kind of polyurethane foam’, says Verhoeven. In agriculture, small drones can quickly find the weak points in a field and create a track of radio signals to a walking robot that can then move back and forth directly to do something about it. If one robot breaks down, another robot in the swarm quickly takes over its work. ‘We keep the individual robots or drones as simple as possible’, says Verhoeven. ‘Their strength lies in working together. It's like a nest of ants that can achieve a lot of work in a large group.’

"In other words, the robots will not be working alone but in a group, or swarm."

Expanding the swarm

According to Verhoeven, the equipment a Zebro-robot is fitted with in order to observe the world depends on the application. ‘They can be fitted with cameras, radars, range finders, temperature sensors or echo-location equipment’, he says. ‘Everything is possible, but we look carefully to decide what is necessary, just like in the natural world. Animals tend not to have redundant skills, as you can see from fish in dark caves that no longer have eyes.’

It's important for the robots to be independent and to be able to find their own way in the world. This is what makes a swarm robust. Verhoeven compares it to videos of drones that he saw on the internet. ‘They execute the most beautiful choreography at amazing speed, but are controlled directly by a large computer, a kind of supervisor. If the connection is lost, a drone like that stops working’, he says. ‘That's not what we want. Our drones look only at the world and each other. This also means that we can effortlessly expand the swarm.’

Taming robots

The Zebro robots are currently still ‘wild animals’ and will at some point need to be ‘tamed’. ‘We are not yet sure exactly how they should behave’, says Verhoeven. ‘That will become clear when we start to use them. I like to compare them with wolves, which people turned into dogs.’ Verhoeven is enthusiastic about releasing swarms of wild robots, but is he not afraid of them being used for evil purposes? ‘Of course, there are people who would want to do that’, he says. ‘You can also make a dog into a fighting dog, but that doesn't make me afraid of dogs in general.’

Swarms of wild robots – that sounds rather unsettling, doesn't it? Verhoeven thinks it is something we will ultimately become accustomed to. ‘People have always been scared of technology – also of cars, electricity or trains. Ultimately, everyone benefits, and in twenty years' time, we will say, do you remember people reacting like that?’

Copying beetles

Verhoeven also takes his work home with him – or at least he is surrounded by six-legged creatures there, too. He takes inspiration from beetles, which he keeps at home. ‘I like to observe their strategy for survival’, he says. ‘What do they do when they are lying helplessly on their back? It seems that they do little until another beetle passes by for them to grab onto. This has taught me that you need to keep your systems simple. Thinking is deadly. Smart robots appear to get into difficulties more easily.’To the moon

There could soon be a Zebro robot walking on the moon. Verhoeven and his team are working on a moon robot. There have already been several driving robots on the moon, but legs have a major advantage: they will not get stuck in the fine moon sand so easily. ‘A sunken leg can be pulled up and placed back onto the surface, whereas a wheel can quickly become lodged’, says Verhoeven. ‘If we have our way, there could be a Zebro on a scheduled moon mission next year.’Text: Roel van der Heijden | Photo: Mark Prins | May 2017

Anyone walking through associate professor Chris Verhoeven's lab at TU Delft will see a miniature animal kingdom. Some of the animals are a metre in length and others just the size of a matchbox. Some can fly, others walk or swim, and all of them have different characteristics. But there is not a biologist to be seen anywhere in the vicinity. Verhoeven is developing the ‘animals’ of the future: robots in all shapes and sizes. The most successful species from the lab have six legs that enable them to negotiate obstacles with ease. They were what gave the Zebro project its name (ZEsBenige Robot is the Dutch term for six-legged robot).

Anyone walking through associate professor Chris Verhoeven's lab at TU Delft will see a miniature animal kingdom. Some of the animals are a metre in length and others just the size of a matchbox. Some can fly, others walk or swim, and all of them have different characteristics. But there is not a biologist to be seen anywhere in the vicinity. Verhoeven is developing the ‘animals’ of the future: robots in all shapes and sizes. The most successful species from the lab have six legs that enable them to negotiate obstacles with ease. They were what gave the Zebro project its name (ZEsBenige Robot is the Dutch term for six-legged robot).