Design for Deaf culture and health

Patients failing to take their medication in the prescribed manner is a widespread problem across society. But a combination of social barriers, discrimination and difficulty with written language mean that the Deaf community has a greater struggle. This medication non-adherence can be dangerous for patients, prolong sickness and strained healthcare systems. Ph.D. researcher Prangnat Chininthorn wanted to find ways to improve this and help Deaf people better manage their own health.

Many think of Deaf people as simply those who have difficulty hearing, but Chininthorn knows that the Deaf community has its own, particular culture of communication. And she wants to make sure that this style is reflected in products designed for them. Chininthorn’s PhD research focused on developing an app to provide Deaf people with accurate health information to combat medication non-adherence.

Originally from Thailand, Prangnat says she was fortunate to have been an exchange student in the United States before moving to the Netherlands for her master’s degree. “I knew I had to adapt myself,” she says, an attitude that helped her later adjust to living in South Africa for her research and to insinuate herself into the Deaf community there.

Chininthorn first arrived at the Faculty of Industrial Design Engineering in 2009 to complete a master’s in Medisign but after seeing an ad for a graduating student to help with a research project with the Deaf community in South Africa, she switched to Integrated Product Design. The project was sponsored by a grant from the South Africa-Netherlands Research Programme on Alternatives in Development, a programme that fostered cooperation between South African and Dutch researchers.

She worked with Bridging Application and Network Gaps, or BANG, an organisation at the University of the Western Cape that helps marginalised groups improve their quality of life. Chininthorn found her experience living with the Dutch really helped her adapt to living with the Deaf. Like Dutch culture, Deaf culture is very direct and straightforward. “For instance, Deaf people acknowledge physical change, like wrinkles or weight gain, much more than hearing people because their language is so tied to the physical,” she says.

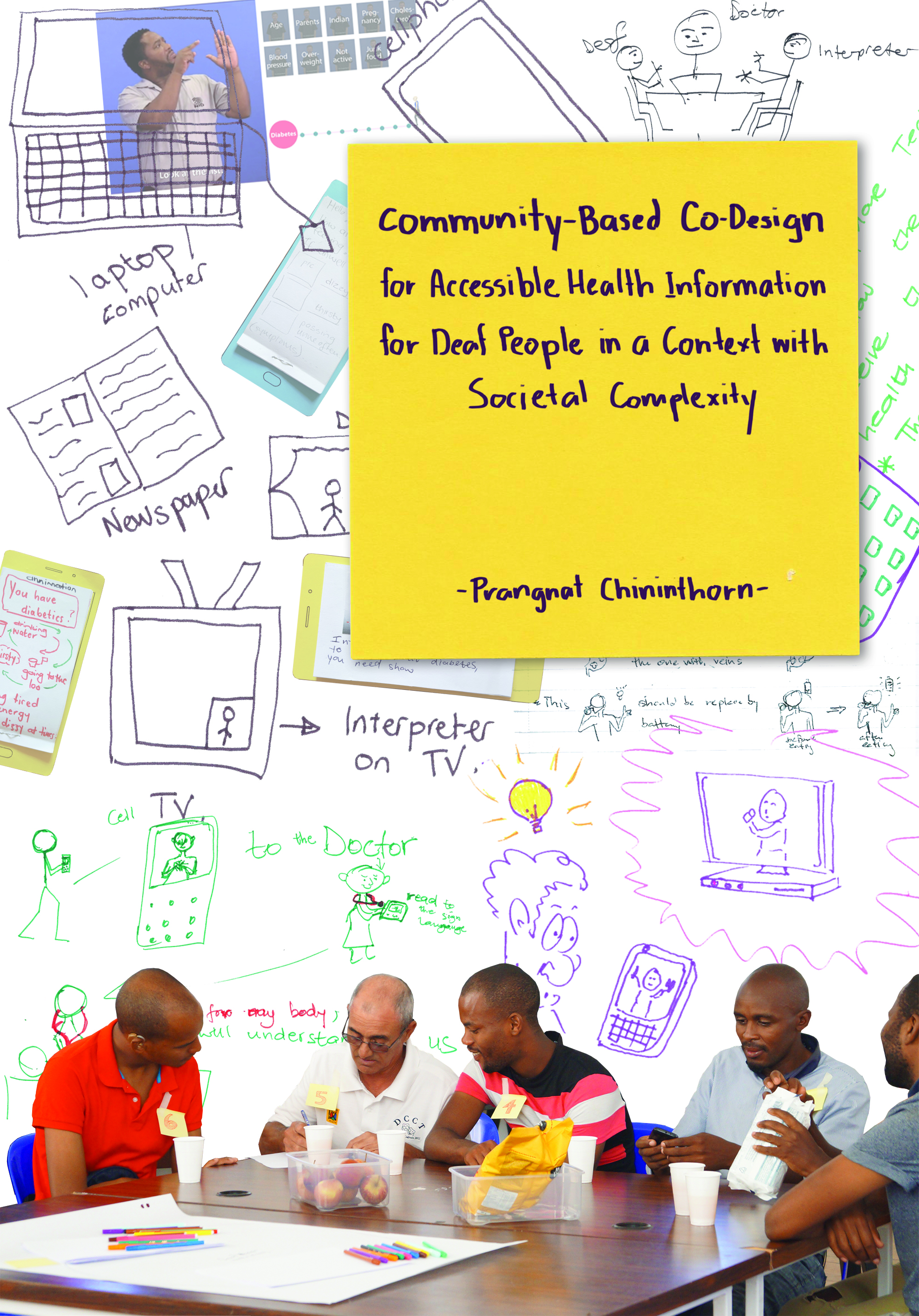

After completing the evaluations for her master’s thesis, she realised people were still skeptical of the medical information they were given. “I felt like I could do more,” she says. Sponsored by a university in Thailand, she was able to continue her research and pursue a Ph.D. using a research framework called community-based co-design. The method treats stakeholders as co-designers, rather than using what she calls a “programmer mindset”, where the Deaf community is treated simply as the end-user and not an active participant in the process.

The Deaf community itself choose the idea for a mobile app. Around 80% of Deaf people in Chininthorn’s study have a smartphone. The number of Deaf smartphone users has increased significantly in the past few years, as video calling has become more common. Sign language communication necessitates such face-to-face interactions.

Chininthorn wanted the app to be useful for both the Deaf and the medical community, so she also included healthcare workers who had some experience with the Deaf community in her brainstorming sessions.

Her final Ph.D. thesis had two main takeaways. First, she developed a guide for understanding how to use community-based co-design with the Deaf community and, secondly, she created a framework for how to design medical apps that medical workers can use to communicate with Deaf people.

Although Chininthorn has had experience living all over the world, she has since returned to Thailand and has found returning home can be challenging. “I have culture shock to my own culture,” she says. She hopes to continue working with the Deaf community in Thailand using community-based co-design and would like to see the approach used with other groups.

Chininthorn had no experience with the Deaf community when she began her research. She learned to “speak” South African Sign Language (Sign languages are not a monolith, they vary by place) with the community there. “I want to advocate on behalf of Deaf people,” she says. By seeing a Deaf person as someone who “can’t hear” you are already restricting their ability.

Jo van Engelen

- +31 15 27 89925

- J.M.L.vanEngelen@tudelft.nl

-

Room B-3-340

Jan Carel Diehl

- +31 (0)15 27 89729

- J.C.Diehl@tudelft.nl

-

Room B-3-350

"To make design for the unknown known!"

![[Translate to English:] A health educational video presented to a deaf participant during co-evaluation](https://filelist.tudelft.nl/IO/Onderzoek/Discover_Design/PhD/Prangnat%20Chininthorn/70.%20A%20health%20educational%20video%20presented%20to%20a%20Deaf%20participant%20during%20co-evaluation..jpg)

![[Translate to English:] A brainstorm session participant holding cue cards](https://filelist.tudelft.nl/IO/Onderzoek/Discover_Design/PhD/Prangnat%20Chininthorn/20160505_162143.jpg)