Getting personal with dementia care

Caring for people with dementia is not a one-size-fits-all kind of thing. That’s because people have different personalities, life experiences and preferences. Taking these things into account, Gubing Wang’s PhD explored how to facilitate designers and healthcare professionals with designing for personalised dementia care.

A family matter

When Wang’s own grandmother was diagnosed with vascular dementia a few years ago, it influenced the direction of her research. Living abroad in The Netherlands, she couldn’t provide care in person so she decided one way to help was by working on design for dementia care. Unfortunately, Wang and her family are not alone. Because of the world’s ageing population, a growing percentage of people will be living with dementia, which means families will increasingly be caregivers. “I think this is not only a personal issue, but also a societal one,” she said.

Specifically, Wang’s research looked into the behavioural and psychological symptoms of dementia (BPSD), the most prevalent symptoms that affect people living with dementia. About 97 percent of people with dementia will experience at least one symptom during the course of their disease. Examples of BPSD are anxiety, aggression or apathy. These symptoms are the most complex, costly and stressful aspects of dementia care. Seeing personalisation as a way forward, Wang set out to investigate how design can be instrumental in the process.

Human-centered design

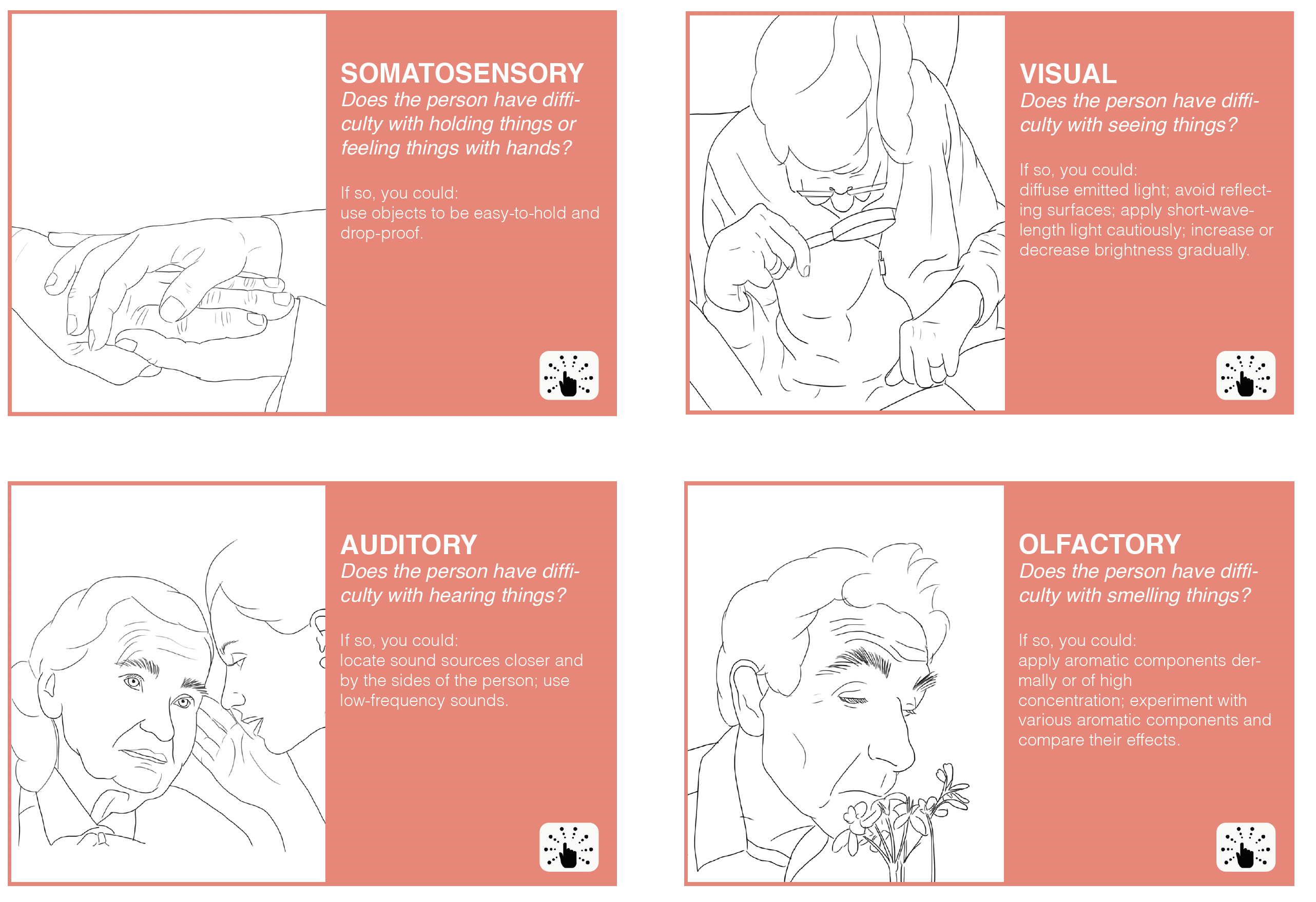

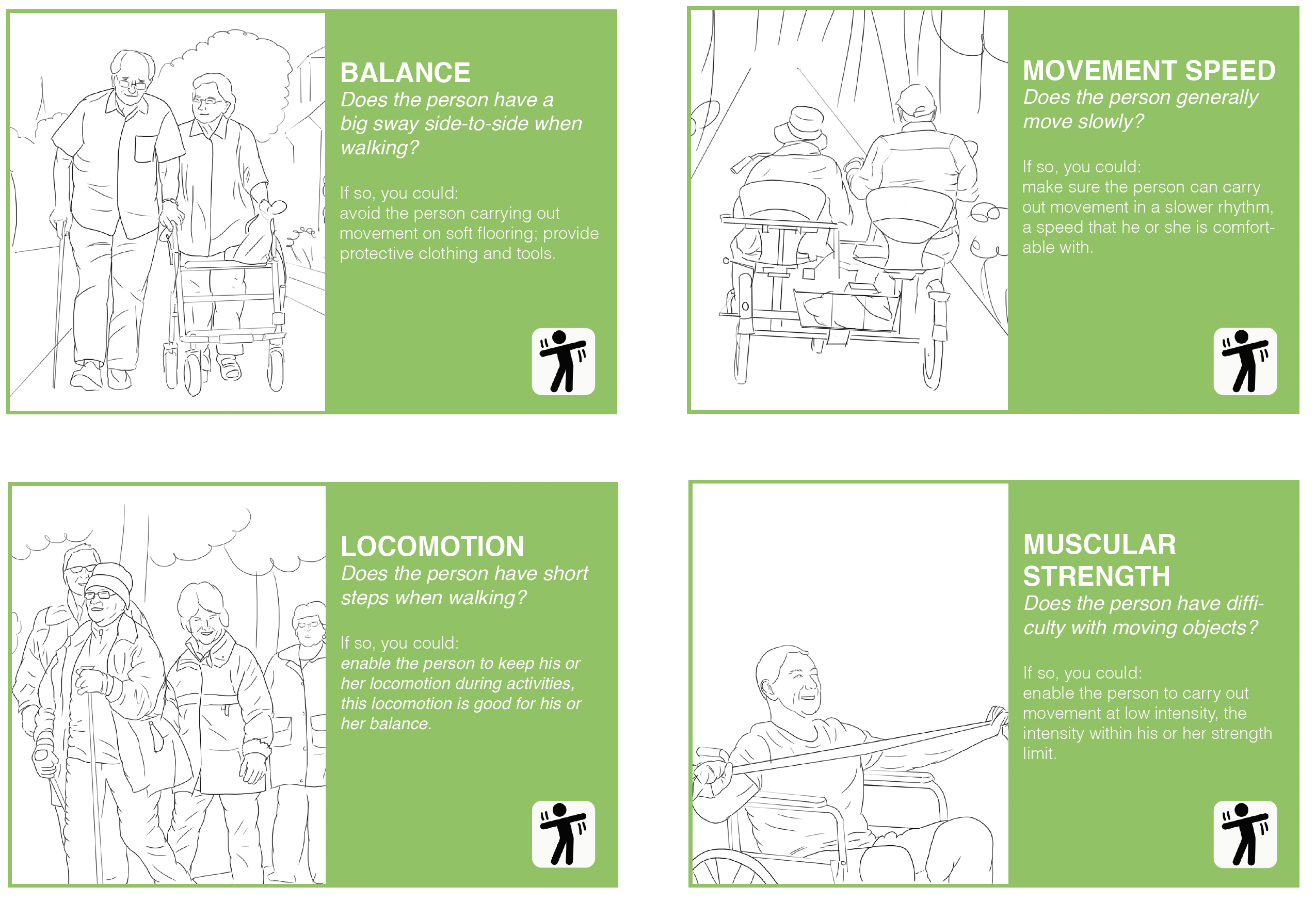

Through the lens of human-centered design, Wang explored three design approaches. First, with ergonomics in ageing, she looked at the capabilities of older adults and how to design things that are usable for people with dementia. Usability is the pre-requisite of a desirable design. Next, with co-design, she investigated how designers can involve people with dementia in the design process. And finally, with data enabled design, she looked at how designers and healthcare professionals can leverage data to gather more insights about people with dementia and the context that they are living in.

With the data enabled design approach, Wang collected location data of the caregivers and residents in a nursing home with an indoor positioning system. “From the location data you can derive some parameters for each person with dementia that are relevant to him or her,” she explained. “For example, with a resident who tends to wander we think the walking distance is more relevant to him. With another resident who is immobile, while she likes to ask for help when she is feeling stressed, then we think the interaction time between her and other people is more valuable.” So, for different people, the parameters used to understand their behaviours should be tailored for facilitating personalised care.

Design is not just for designers

By integrating these three different design approaches, Wang created the Know-me toolkit, which can help future designers and caregivers to design for personalised dementia care. And she believes that everyone can design. “Currently this toolkit is meant for designers to use in collaboration with healthcare professionals, but maybe in the future we can develop a few different versions that can be used for the general public. In this way, the caregivers for people with dementia, who know people with dementia the best, could be empowered to design for the people they are caring for,” she said. “For example, a daughter can design for her mother, a husband can design for his wife. I think this design process not only solves some care issues, but also strengthens the bonding between people.”

What’s next?

Wang’s main research interest lies at the intersection of design, technology, and healthcare. As for life post-PhD, she said: “Specifically, I would like to explore how design might shape relevant technologies in improving the health and the wellness of people around the world.”

Gubing Wang

- +31 (0)15 27 82225

- g.wang-2@tudelft.nl

-

Room C-2-130

Mo-Tu-We-Th-Fr

Tischa van der Cammen

- +31 (0)15 27 83021

- t.j.m.vandercammen@tudelft.nl

- Publications

-

Room C-3-180

"Autonomous ageing"

Armagan Albayrak

- +31 (0)15 27 81932

- A.Albayrak@tudelft.nl

-

Room C-3-080