Can the current system of linear production methods and consumption patterns be transformed into a circular economy with more value retention? The three winners of the first circularity prize for budding architects are convinced it is possible. For example, there is no need to throw out insulating glass because it has signs of wear and tear, and houses can be constructed of locally grown hemp.

A multifaceted theme requires a multidisciplinary approach, which is why scientists of the Faculty of Architecture and the Built Environment combine their expertise and bring it to the world through the Circular Built Environment Hub. They are led by Tillmann Klein, Professor of Building Product Innovation. “From components to cities, this faculty is home to knowledge of all levels of scale of the circular built environment. We are looking at different aspects such as design, management or technology. We owe it to society to combine our disciplines and bring together the people who can help achieve a circular economy.” This theme is also taking hold in the Bachelor’s and Master’s degree programmes. For example, students are asked to conduct research into ways to close raw materials cycles or apply renewable materials in their designs. If they are provided with the know-how, the next generation of graduates can help governments and industries to identify challenges and find solutions to them, thinks Klein. This will bring knowledge development and professional practice closer together. “Many graduates are already giving it a shot, which is why we created this annual competition. We want to draw attention to the best projects so that other stakeholders in the construction chain can benefit from them.”

Long live insulating glass

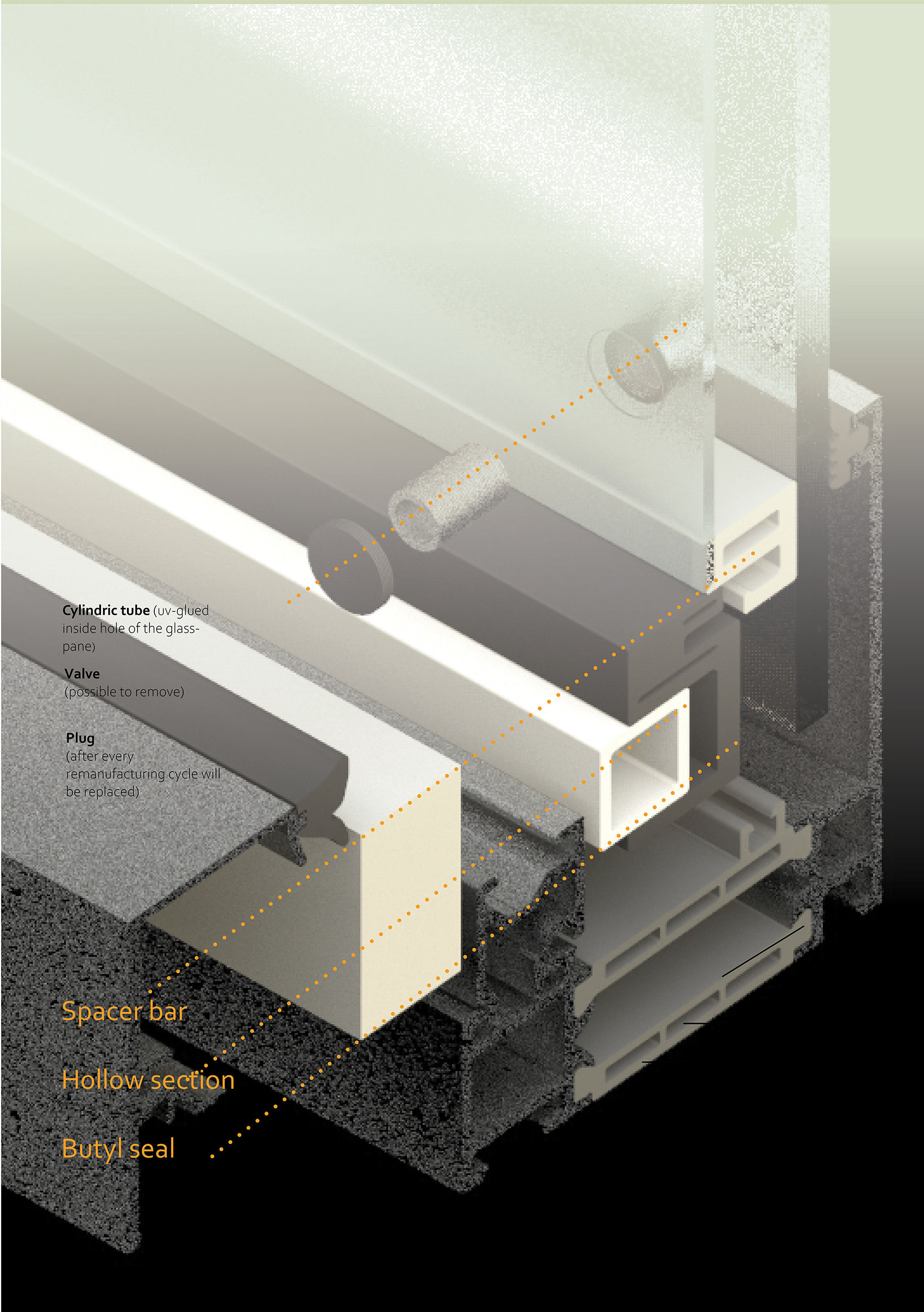

The very first Circularity in the Built Environment Graduation Awards were presented on 24 September. The jury had to consider no less than 42 entries divided into three categories: Materials & Components, Buildings, and Cities & Regions. Juliette Mohamed won the prize in the first category. She graduated on a design for reusable insulating glass, the 're-seal window’. “I started studying Civil Engineering, but the mere design of buildings and building components attracted me so much – my fellow students called me ‘the little architect’ – that I also decided to take a Master’s degree in Architecture.” Mohamed investigated the useful life of insulating glass as it is applied in millions of buildings around the world. Insulating glass usually consists of two or three layers with air or gas in between. Spacers are placed between the panes at the edges and the panes and spacers are sealed with rubber and sealant. “After about fifteen years, the seal becomes so worn that it starts to leak and moisture gets between the glass panes, reducing the insulating effect. At some point the glass needs to be replaced, but it is rarely recycled because of the coatings and sealant residues, so much insulating glass ends up as construction waste.”

She wondered if there was another way and set about designing a method to renew the seal on site, while the glass is still in the frame: a ‘re-seal window’. Thanks to this method, the insulating glass lasts for much longer. "I tinkered with computer models and tried out different variants. I even drilled various test holes in the studio of a glassmaker in Leiden to find out if it was possible to refill the window with air or gas.” She eventually came up with a combination of a self-designed spacer and a removable and replaceable seal that makes it possible to refurbish the insulated glass. “I printed 3D dummies of window parts and tested them for properties such as elasticity in the faculty’s LAMA lab. The parts performed well, as was confirmed by the computer model.” She is now eager to test the whole set-up in practice to see if it functions adequately. “We engineers need to conceive sustainable solutions, but they also have to be easy to apply and affordable, otherwise our designs will not be embraced. That is precisely what I have tried to do.”

Grow your own house

Job van den Heuvel was inspired by the ‘open-building’ philosophy advocated by John Habraken and Frans van der Werf in the 1960s. He considered how the new Strandeiland neighbourhood in Amsterdam’s IJburg district could be encouraged to be grown, both from an social as an ecological perspective. “Could we grow a building material on site?” he wondered, “and how could residents and future users play a role in this process?” ‘Open building’ is based on the idea that residents and users should always be able modify a house’s interior (the infill) to meet their own wishes, while the supporting structures (the support) remain unchanged. “You could say that the more flexibility you offer, the more durability you get. Because new users are constantly adapting the buildings, they can continue to be used for two hundred years and longer.” Amsterdam wants to build 8000 new homes in Strandeiland, and the municipality is keen for the development to be as circular as possible.

Van den Heuvel combined the principle of support and infill with the principle of biobased building. He discovered that fast-growing industrial hemp is also suited to the production of high-quality building materials. “My strategy, called ‘WeGrowCo’, involves creating buildings with a supporting structure made of timber and a modular interior made of hemp. That hemp is grown on the spot, which also happens to greatly increase the fertility of the soil – a nice bonus.” Future residents can make hemp-lime components from the harvested crop – possibly supported by the municipality and professionals – which they can then use to manufacture interior components. This will be done in communal workplaces designed by Van den Heuvel. “Step 3 involves using the components to build houses around these workplaces, which will become social meeting places in the neighbourhood.” He calculated how much hemp is needed, how much land the crop requires and how quickly it can be harvested. He then designed a zoning plan for the hemp crops and a timeline for development.

Hemp buildings are not science fiction, he insists. “In fact they already exist, here in the Netherlands too, but not on the large scale that I am suggesting.” He wants to do something about this, but now as an entrepreneur. "I have created a start-up to help design and advise and so bring this holistic approach to fruition.”

Circular area development

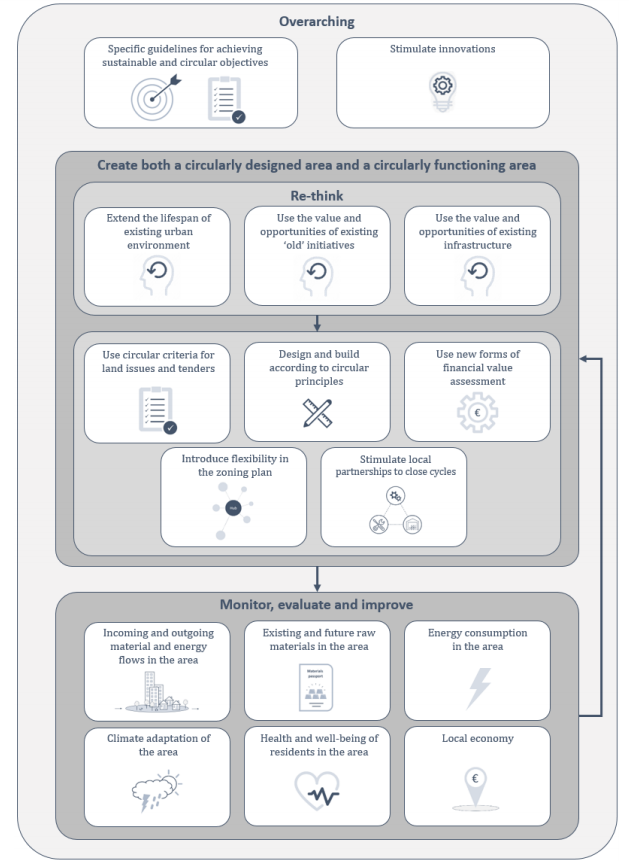

Windows and houses are not the only things subject to sustainable reinterpretations; spatial plans can also be improved. Sven van Bakel studied how to achieve circular area development, and offered recommendations. "I previously studied at Amsterdam University of Applied Sciences, and graduated on the subject of circular construction. To some extent, my interest in project and area development was piqued by a work placement and part-time job with a developing contractor.” He realised that a ‘circular’ area development is the sum of a circular design and a circular system. “The private sector usually takes care of the design, while the government creates the conditions for achieving a functioning circular system. ‘Circular’ area development hence requires the involvement of both the public and the private sector. My recommendations primarily concern the necessary steps in the planning process.”

Among other things, Van Bakel studied the development of a former industrial zone on the northern bank of the IJ in Amsterdam between 2013 and 2018. “I compared construction projects and linked them to figures on incoming and outgoing materials flows.” He observed a considerable increase in the number of new houses and the quantities of incoming and outgoing materials. “The government wants the economy of the Netherlands to be fully circular by 2050, but in Amsterdam the space and capacity to store and reuse materials locally actually decreased as part of the complete transformation of this zone into living and working space.”

In other words, if you want to create a circular district where materials are reused, do not plan for so many homes and commercial spaces that there is no room left for activities to support your circular ambitions. “For example, a concrete plant or a woodworking company in the neighbourhood can actually be of great value if you want to use your building materials as sustainably as possible. Functions that are at odds must be carefully considered well in advance to be able to design a responsible circular area development plan.” Other recommendations include valuing circularity in area development financing plans and stimulating innovative business activity. “Unfortunately, the coronavirus crisis has prevented me from testing these recommendations in practice for a municipality or project developer. I hope to get a new opportunity to do this.”

More information

The complete theses are available through these links:

- Juliëtte Mohamed: The re-seal window - A redesign of the edge seal of Insulated Glazing Units to facilitate easy and fast re-manufacturing

- Job van den Heuvel: WeGrowCo – an open-building strategy

- Sven van Bakel: Circular area development: Recommendations for creating a circularly functioning area

Students from the Faculty of Architecture and the Built Environment TU Delft who graduate this academic year on a topic related to circularity can participate in the second edition of the Circularity in the Built Environment Graduation Award.

Juliëtte Mohamed

Job van den Heuvel