Winnifred Noorlander, a Systems & Control student with a passion for entrepreneurship, is working on a new medicine for the treatment of sepsis. A life-threatening response of the body to an infection, sepsis causes 20% of all global deaths – 11 million each year. So how is a student without having any prior knowledge of biotechnology pursuing this research at the faculty of Applied Sciences? Why is she working on a more reliable answer to this highly lethal inflammatory disease?

Research into wastewater bacteria

The story begins years before Winnifred got involved, with the research group of Environmental Biotechnology at the TU Delft. Mark van Loosdrecht, Yuemei Lin and many others have been researching the behaviour of bacteria and wastewater treatment applications for a long time. They discovered that bacteria can convert certain compounds found in wastewater, such as nitrogen, into useful biopolymers.

During this conversion process, the bacteria form a layer called a ‘granule’ around themselves, for protection from the environment. The group found that they could use this process to develop new sustainable materials for a variety of industries such as the paper industry, the agriculture sector and the cement industry. Lin even found out that they can fabricate beautiful earrings from it!

The research showed that, under the right conditions, the bacteria are able to develop different complex sugars. Complex molecules like these are usually found only in higher organisms such as mammals or crustaceans, so locating and extracting these sugars from bacteria would be quite extraordinary. The group patented the process by which these bacteria produce their granular shape, because they suspected there could be many innovative applications.

Discovering the patent

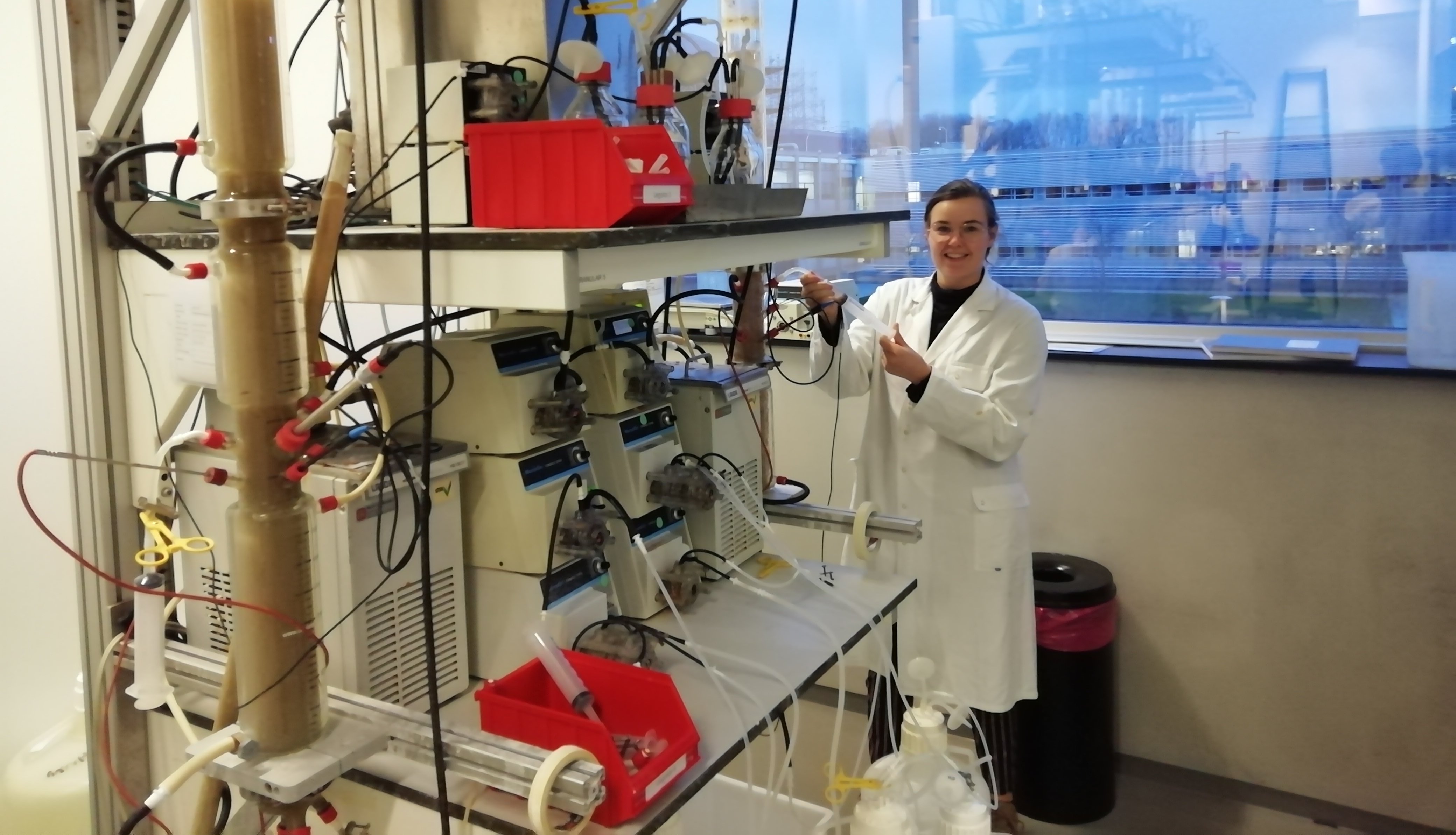

At this point, in came Winnifred Noorlander, a then 25-year-old Masters student who felt like she was missing something in her studies. Winnifred had a clear idea what her passion was: being an entrepreneur. But her Masters had no focus on entrepreneurship, so she followed some extra courses alongside her standard curriculum. During the course ‘Turning Technology into Business’ by Dap Hartmann, she reviewed many different patents to see if there was an opportunity lying in wait.

The first time I went over the patent, I didn’t even understand half of it, but together with a couple of other students and with the help of the Environmental Biotechnology researchers, I took a deep dive into the literature and slowly started to understand more and more.

That was when Winnifred came across the patent of van Loosdrecht and Lin. At this point she had no previous interest in biotechnology, and she knew virtually nothing about it: “The first time I went over the patent, I didn’t even understand half of it, but together with a couple of other students and with the help of the Environmental Biotechnology researchers, I took a deep dive into the literature and slowly started to understand more and more.”

Looking into multiple business cases for the patent, Winnifred stumbled upon something quite interesting: since the sugars are so intricately designed by nature, they are extremely difficult and expensive to synthesize. Being able to produce them using bacteria would be a real game changer. For example, one particular type of sugar (heparin) is extracted from porcine intestine for a number of lifesaving treatments. Not only is this a very complicated process, but demand has for years been higher than the supply.

Making a difference

After learning this, Winnifred threw herself into the research: “I saw an opportunity to make a difference by helping to solve a global issue. Also, I love solving complex puzzles and this was definitely the biggest puzzle I could find.”

The great thing about working with TU Delft was the vast amount of knowledge and hands-on help from the inventors. Long after her course ended, Winnifred started testing in the labs, and continued to educate herself in the field of biotechnology. She also looked for help elsewhere, talking to intensive care doctors about their experiences and working on a financial plan for the project, looking for grant funding. Winnifred identified her knowledge gaps and reached out to partners who could fill them in. These included Delft Enterprises and also Sanquin, who helped her test how her compounds compared to compounds already on the market. Together they looked into a relatively new application for this type of heparin: sepsis.

Sepsis

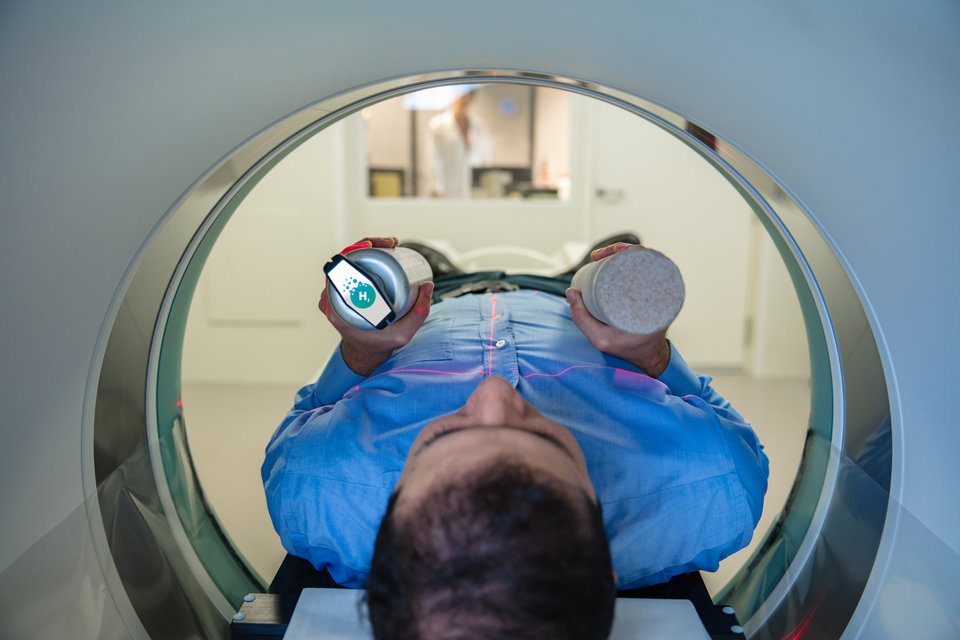

Sepsis was another thing Winnifred hadn’t heard about before. She was shocked to find that 20% of all global deaths are sepsis related. The current treatments are simple antibiotics, but these aren’t very effective since they only work on bacteria as a pathogen source. In a new clinical study, the heparin-like compound has been shown to have a very promising effect in reducing the body’s inflammation reaction. This medicine, which is being developed, uses the same complex sugars as in the patent, but is currently still produced from porcine intestine.

20% of all global deaths are sepsis related

Restricted existing supplies mean there is enormous potential for using bacteria grown from synthetic wastewater as a resource to produce a heparin-like compound. This would make it much easier to produce a similar medicine, and would be independent of the availability of porcine intestine. A production process like this could be easily scaled up hugely, depending on how much of the medicine is needed, since the technique has already been implemented on a large scale at wastewater plants. Achieving this is what still drives Winnifred to work daily.

What’s next?

Over the past two years, a lot of steps have been made in the right direction, but there is still more research to be done. For the coming year Winnifred is looking into the exact composition of the complex sugars and what this would mean for the human body. When the chemical footprint has been further characterised, it will still need to be purified extensively before the start of clinical trials. Hopefully, in the future, this will lead to using wastewater treatment technologies in other fields that can potentially save millions of lives every year.

Looking for help

At the moment, Winnifred is in search of another like-minded, enthusiastic, individual to help her bring this idea to life. She is actively looking for someone to work with her on the project on a full-time basis, preferable with a chemistry/life science and technology background. So, if you are interested or know someone who is interested in joining this adventure you can get in touch with the team at TU Delft Campus or send her a message on LinkedIn.

Investment from Delft Enterprises Incubation Fund

Winnifred is the first person to receive an investment from the recently established DE Incubation Fund. She was awarded 50.000 Euros – in tranches of 15000 and 35000 Euros – to demonstrate the feasibility of her project.

The DE Incubation Fund was formed to support idea-stage projects at TU Delft with potential commercial prospects. The Fund makes a number of awards each year to support novel ideas that, if successful, will lead to new spin-off companies. The fund is administered by Delft Enterprises and Teggwings. Are you working on an innovative, early-stage project and interested in support from DE Incubation Fund? Contact Ronald Gelderblom.

Text: Sarah Bennink Bolt