Could clouds be modified to slow global warming? Cloud expert Herman Russchenberg is investigating climate intervention but hopes his theories will never be put to the test. The scientific director of TU Delft’s Climate Action Programme says it’s crucial to focus on ways of achieving zero CO2 emissions first and foremost, and for people to adapt to climate change. But a €22m investment will create space for the development of tools to be used in case of climate emergencies. ‘Climate engineering is like a fire engine. You hope you’ll never need one but it’s good to have one on stand-by.’

The most recent IPCC report has shown once again that climate change is the greatest challenge we are faced with and science is at the forefront of the battle. The research into causes, effects and possible solutions to the crisis carried out in the Climate Action Programme provides an extra boost to the troops. ‘We need to achieve a better understanding of how and why the climate is changing and what the impact of these changes are,’ Russchenberg explains. ‘In addition to that we are looking for ways and techniques to combat global warming, or climate mitigation. Adaptation – ways to reduce the effects of climate change on humans - is another area we are investigating. The final research topic is the role of politics and society in climate measures.’

Tinkering with the climate

Climate engineering (see box) forms part of the TU Delft programme and is a relatively new contribution to the climate debate. ‘Technologies which influence climate have been with us for some time but have always been a bit of a taboo subject. Politicians in particular are afraid that using technology will weaken the sense of urgency which drives CO2 emission reduction. Far-reaching interventions of this kind have the additional disadvantage of unpredictability. We do not know what the long-term effects will be. This research will hopefully incentivise the discussion between science, politics, business and citizens.’

Climate engineering

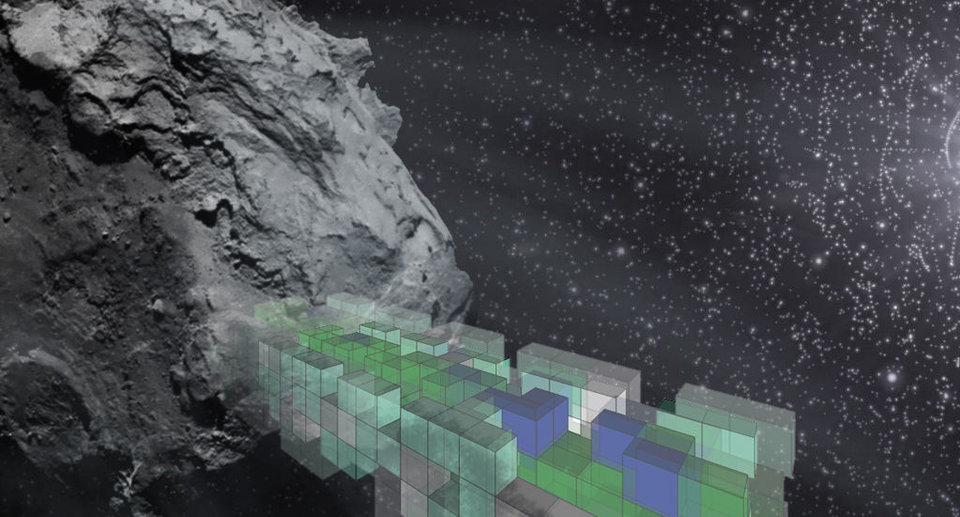

Climate engineering is the intervention in the natural systems of the earth aimed at comabting climate change and, more specifically, global warming. Climate engineering is divided into two categories: solar radiation management (SRM) en carbon dioxide removal (CDR) technologies. SRM is aimed at reflecting or filtering sunlight to lower the earth’s temperature.CDR comprises methods to remove CO2 from the atmosphere and store it, for instance, in empty gas fields beneath the seafloor.

Emergency tool

Knowledge is the basis, Russchenberg says. ‘We need to find out what works and what doesn’t work, what the effects and risks of climate intervention are and how we can limit them.’ It’s important to look on climate intervention not as a solution but as a tool that we might need at some point, Russchenburg emphasises. ‘The primary aim is mitigation, achieving zero CO2 emissions. The next step is adaptation and if all else fails we may have to turn to climate engineering. Policians and policy makers must create the proper conditions for a possible application. The organisational and ethical sides of the question are also important. This is about much more than technology alone.’

Strategic knowledge

One of the challenges of climate engineering is to get it onto the international agenda, Russchenberg says. ‘We can’t leave this to a single country. Abuse is a very real possibility, for instance, if one country manipulates the weather to suit its purposes at the expense of others. It’s important to build a knowledge base here in the Netherlands and share that knowledge with other countries. The European member states would be the initial discussion partners and from there a wider discussion with other blocs could follow.This means that knowledge about climate engineering becomes important strategic knowledge.’

Cloud research

Russchenberg, who is professor of Atmospheric Remote Sensing, concentrates most of his research efforts on clouds, which form an important part of our climate system. They store heat and reflect sunlight. Without clouds the earth would be 10 degrees warmer than it is now. Unfortunately the increase in CO2 in the atmosphere is affecting their cooling capacity. ‘Climate engineering could help remedy this,’ Russchenberg says. ‘ Adding aerosols to the clouds would help restore their cooling ability. Aerosols promote the formation of cloud droplets. The more droplets, the more sunlight is reflected. Of course the right kind of aerosols would have to be injected into the cloud, in the right place and in such a way as to keep the process going.’

Over the ocean

Oceanic clouds would be the most logical candidates for aerolsol injections, Russchenberg says. The air over the oceans is cleaner than above land, for one. Cloud formation is also more prolific there with plenty of water to turn into vapour. As soon a salt crystals reach a cloud droplets are formed. One idea Russchenberg has been entertaining is to have unmanned vessels shoot salt crystals into the clouds above. ‘The vessels would have to be powered by clean energy of course and the pumping and injection process would have to be sustainable. We don’t need more polluntants in the atmosphere.’

Risks and consequences

The development of such vessels is nowhere near to being a reality, Russchenberg emphasises. ‘What we are doing now is studying the physiological processes that take place in clouds and the effects on climate. One of the risks could be, for instance, that more small droplets form and the cloud evaporates more rapidly. That would mean more direct solar radiation, the opposite of what we want to achieve. Another unintended effect might be that during droplet formation the cloud cover moves in such a way as to change rainfall distribution. And that will affect food production and water provision. We can only add this tool to the climate tool kit if we understand the processes and their consequences.’

Fire engine

Russchenberg is adamant that climate engineering should be a last resort. ‘As a scientist I am interested in technology but its application is not my ultimate goal. That would be to preserve the liveability of the planet. But we owe it to ourselves to keep all options open. If we put all our eggs in one basket we will come a cropper. I sometimes compare climate engineering to a fire engine. You hope you’ll never need one but you do need to develop them and keep one close by just in case.

Published: September 2021

About the Climate Action programma

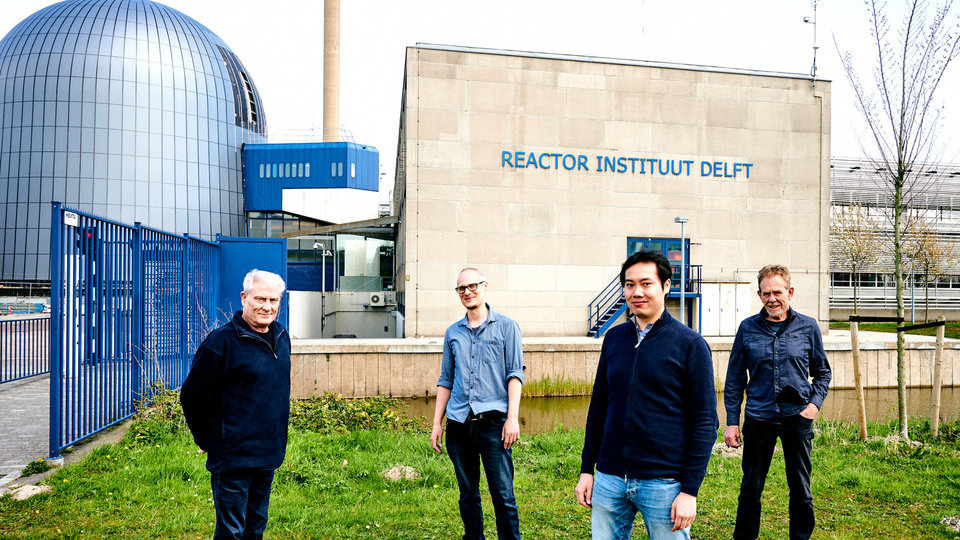

In April 2019, TU Delft published its vision document outlining the need for far-reaching action on climate. This new Climate Action Programme builds extensively and in concrete terms on the vision document, featuring plans for research, education, action on climate on TU Delft campus and cooperation with the worlds of politics and industry. Prof Herman Russchenberg will act as chair/scientific director of the programme.

The research component of the programme is based on four themes: Climate Science (monitoring and modelling to identify what is happening with the climate), Climate Change Mitigation (what action can we (still) take in order to combat climate change?), Climate Change Adaptation (how can we adapt to a changing climate?) and Climate Governance (what can we do to support politics and society in taking climate measures?).