Breaking with tradition, the tenth Delft Solar Boat team decided to take part in the offshore race in the Solar & Energy Boat Challenge in 2019. “The thing that makes the Delft dream teams unique is that each team can set its own goals for the year,” says Redmer Aarnink, who was exposure manager on the team. “It is fantastic for teams to be able to start from scratch and build their own boats. That isn’t absolutely necessary, but it is often essential because the race rules change or you decide to take part in a different race. And in this case, even an entirely different class, in which no team from Delft, or any other Dutch team, had ever competed before.”

Seaworthy

An entirely new class placed different demands on the boat. “There was actually only one hard and fast rule: the boat had to be no longer than 12 metres. That meant we didn’t have much to guide us; we only knew that we had to be seaworthy,” says Hull Design Engineer, Willemijn Mes. The final design was therefore completely different to previous versions: a trimaran with no fewer than 28 m2 of solar panels and a crew of three. “Because the boat was much bigger, it also had to be disassembled for transport,” says Mes. Plenty of design challenges, in other words. “The more parts you need to be able to loosen and tighten, the more can go wrong in production or during the race itself. That made the design very complex,” says Mes. Moreover, neither she nor the other team members had ever built a boat before. “I’m studying civil engineering, so boat building might not seem an obvious project, but the whole point of taking part is to learn. Besides, I’ve been sailing all my life. A trimaran is a little bit like a yacht in terms of design; only the propulsion is different.”

Outside your comfort zone

Becoming exposure manager was outside Aarnink’s comfort zone too. “I really wanted to be project manager, but the former team members thought that this would be a good role for me. Looking back, I can understand why. I’m studying applied physics and I have a broad technical background; that means I understand and can explain all the engineering in the boat up to a certain level.” He sometimes found his role difficult. “In contrast to the other team members, I didn’t have a specific goal to aim for. I tried to share our story with as many people as possible, but how many do you reach and how effective is that? It’s a completely different way of looking at things than in physics and I learned a lot.”

That learning process is essential for the dream teams working on ambitious projects such as building a solar-powered boat in the D:DREAM Hall on campus. D:DREAM stands for Delft: Dream Realization of Extremely Advanced Machines. It is the place where teams of students from all parts of the university spend a whole year working towards a common goal. They do everything themselves, from designing to building to project management, and in passing, they learn skills that will serve them in good stead after they graduate too.

Learning process

Making mistakes is all part of the learning process. Aarnink: “In the early months, I suddenly got a phone call from Radio 2 asking if I could take part in a live interview lasting two minutes. I’d prepared really well, but what I hadn’t understood was that I had to stop when they said so. So I just carried on talking and when I was interrupted halfway through, I thought, ‘what’s going on now?’ I had spent the whole day manning a stand at a trade fair and it was half past eleven in the evening, so that explains a lot. I hadn’t done any media training either, because I hadn’t expected the press to be interested until later on. Luckily I can laugh about it now.”

Hard work

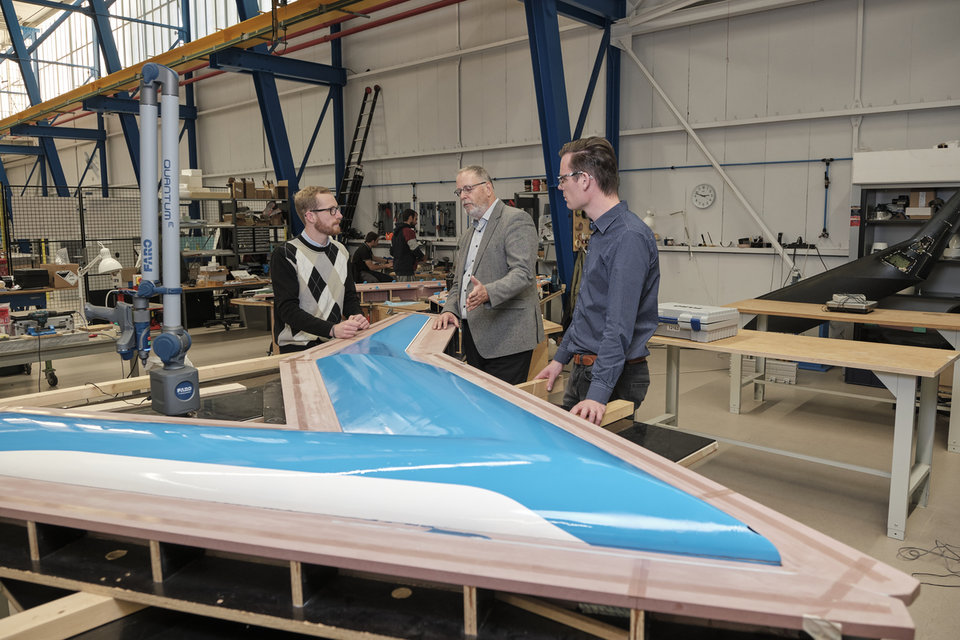

The biggest challenge for Mes was the production process: “When building the hulls, we were able to make use of the production facilities of our partner VABO Composites in Emmeloord. We did everything ourselves, but it was good to be able to ask them for help. It was hard work and also challenging to spend three months in Emmeloord, only going back to Delft at the weekends.” After that, the various parts – which had been built at different locations – had to be assembled. “That took much longer than we had expected, partly because of the complex design. Everything had to fit together and be able to be taken apart again easily. ”They succeeded in the end. “As a team, we built a well-functioning boat which we are very proud of,” says Aarnink. Test sailing on the Westeinderplassen near Aalsmeer also went well. The real test would take place on the IJsselmeer, where the hydrofoils had to prove themselves. “Hydrofoils stick out under the boat. If the boat goes fast enough, they can lift the hull up out of the water a little, so you have much less resistance and you can reach high speeds,” explains Mes.

Disaster

On the IJsselmeer, however, disaster struck: the left front foil broke off. “That was a major setback. Hydrofoils are part of our identity; the Solar Boat has used them for years. It was also terrible for the team; they had worked so hard on it,” says Aarnink. “Months of work were lost in an instant,” adds Mes. Searches with divers and a sonar boat came to nothing, but there was little time to recover from this setback. With only three weeks to go until the race in Monaco, they had no choice but to go without hydrofoils.

The race in Monaco took place on 5 and 6 July. The teams taking part had to sail from Monaco to Ventimiglia and back; once on the first day and twice on the second. “Our competitors all had electric speedboats. They can reach speeds of up to 100 kilometres an hour, but they can’t maintain that speed for long. That’s why they are much less efficient on long distances. So we thought we could make gains on the second day especially,” says Aarnink. “We go more slowly, but we can maintain our speed for much longer,” says Mes. The race would therefore be decided on points at the end of day two.

Smoke

“Things went well on the first day and we came in third,” says Aarnink. “But as the boat returned to harbour, the pilot saw smoke. We turned everything off and towed the boat to shore. We were standing ready with fire extinguishers and never took our eyes off the boat,” says Mes. “We didn’t know what was wrong at first, but later it turned out to be an electrical fault in the solar panels.” Once again, the team was faced with a difficult decision. “We couldn’t start day two like that; safety comes first. But no one likes to give up, and so we decided to remove the solar panels and run on batteries. It was a difficult moment: you’re actually demolishing your own boat.”

Nonetheless, the team kept their spirits up, buoyed by their performance on the first day. “The second day was less predictable. What would the other teams do? You’re allowed to recharge along the way, but then you have to stay in the harbour for three hours as a penalty,” says Aarnink. “We didn’t need to do that, but we weren’t able to sail as fast as we would have liked. But our boat turned out to be so efficient that, in the end, we won with 20 minutes to spare!” says Mes. That led to wild celebrations, and included all thirty team members diving into the harbour. Aarnink: “It was a bizarre moment. The adrenaline kept me awake for three nights.” That was also because the busiest time for him was about to start. “I was doing a radio interview at 6am the next morning and another ten or so throughout the rest of the day.”

Broader outlook

They are now back at their studies again. Aarnink: “I’m looking around to see which Master’s degree programme I want to do. I’m thinking of something like performance coaching.” That has everything to do with his time working on the Solar Boat. “A year like that shapes you and broadens your outlook. You learn a lot about yourself and about the team. Working together so intensively is very special. You can’t win unless everyone on the team does their job.” It has set Mes thinking too. “I think I’m going to do a Master’s in Offshore Engineering. You choose a degree programme without knowing what all the other programmes entail and you tend not to venture outside your own specialist field. The people on the team came from all sorts of disciplines and you learn how others look at things and tackle problems.” Her choice is also connected to the Solar Boat mission: working with the industry on sustainable shipping. “A container ship will never run on solar panels and our boats will never be taken into production. Where we can make an impact is on making the maritime industry aware of how it can become more sustainable,” explains Aarnink. Mes: “Personally, I’ve learned a huge amount about sustainability over this last year. We are the new generation of engineers who will soon be entering the world of business. If you do so with a fresh outlook, you can really make a difference.”