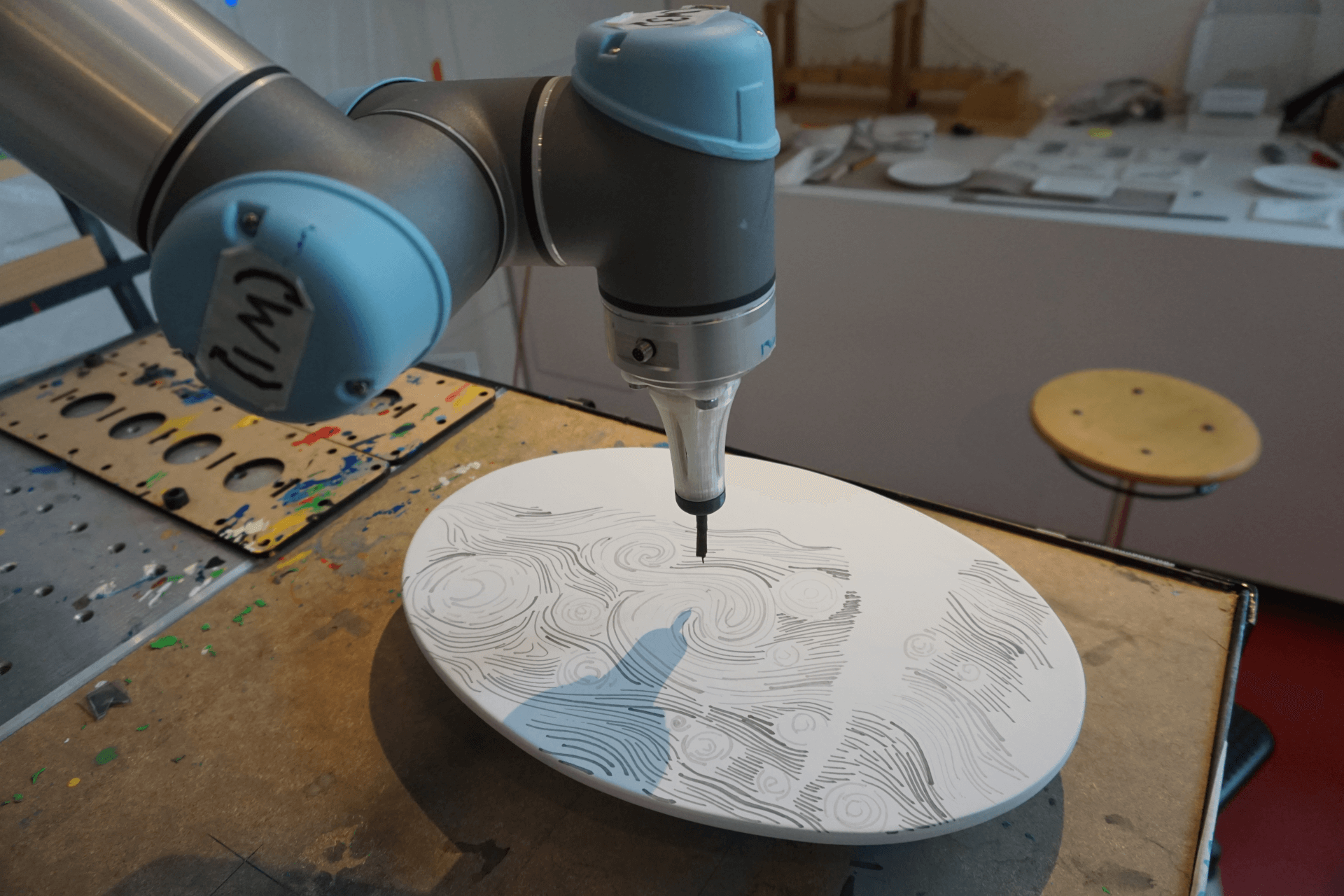

With mathematical precision, a thin brush draws line after line after line across a square piece of ceramic. It is the prelude to a classic Delft Blue tile. Contours of feathers, of a wing, of legs and eyes appear. Everything without hesitation, drawn with a steady hand. When the brush leaves the last line behind, we see an abstract reproduction in tight lines of the famous painting ‘The Goldfinch’ by the Dutch master Carel Fabritius from 1654.

However, the person who wields the brush with such acute precision and utter imperturbability is not a master painter of Delftware, not someone of flesh and blood who has spent years honing his craft, but the painting robot Bob Rob, prepared in just a few months.

Bob Rob has no head and no torso, but only one arm, with which he can handle a brush. Researchers and students at TU Delft’s Faculty of Industrial Design have been experimenting with this robotic arm since 2019. The idea came from assistant professor Doris Aschenbrenner, who specialises in human-robot interaction in digital production methods. Aschenbrenner: “During an art exhibition in Germany, I was having a drink in a café with some friends and acquaintances. While talking, the idea came up to exhibit a painting robot and see how the public would react.”

Easier said than done, because a ready-made paint robot does not exist. Painting is far too difficult for that. Painting requires skill, knowledge of paints and brushes, and of the materials on which the paint must be left for eternity. Artistic painting requires creativity and imagination, and preferably also knowledge of art history.

Aschenbrenner uses a lightweight, flexible robot arm from the Danish company Universal Robots, which she uses for manufacturing tasks as well. In collaboration with two German start-up companies, they started a small research project, a sideline to her own research. The robot arm was named Bob Rob, inspired by the American painting instructor Bob Ross, who gained world fame in the 1980s and 1990s with his TV programme ‘The Joy of Painting’.

The painting robot inspires

“First and foremost, I see our painting robot as an inspiration and as an educational tool for our students,” says Aschenbrenner. “The robot triggers discussions and inspires us to explore new approaches. Typically something that belongs in industrial design. What can the robot do better than humans and what can humans still do better than the robot? Which tasks can we let the robot do together with the human? What role can a robot play in modern digital manufacturing techniques? What do such robots mean for the future of work? As a research project, we combine science with fun in Bob Rob.” The team published the code as open source software to enable students, artists and scientist to use it.

What started as a small side project for Aschenbrenner in 2019 has gotten somewhat out of hand two years later. When Bob Rob got his first art gallery exhibition in 2020 in a small gallery in Germany, the appetite grew for more paintings created by the hand of the robot. And as soon as Bob Rob was painting behind glass in a hall of the faculty for everyone to see, more and more researchers and students became interested. Much of the work fell into the laps of robot technicians Joris van Dam and Neel Nagda.

One day, Professor of Visual Communication Design Catelijne van Middelkoop also walked past the robot while the machine was painting. She immediately fell into conversation with Aschenbrenner, who happened to be standing next to the robot. Van Middelkoop: “I must admit that at first I thought: ‘A painting robot? Funny, but what nonsense.’ In 2016, for the project ‘The Next Rembrandt’, a new Rembrandt-like portrait was already made. What can a robot add to that? I wondered.”

But while talking to Aschenbrenner, Van Middelkoop quickly decided to collaborate. “In my inaugural speech, I argued in favour of bringing art and science closer together. Well, in the Bob Rob project I hope that there will be a cross-pollination between engineers and creatives.”

Van Middelkoop first had Bob Rob paint simple line exercises that were used during the so-called ‘Vorkurs’, the admission year of the 20th century Bauhaus. Just to see how the robot handles brush and paint and what characters the lines can radiate. After those first line exercises, she had Bob Rob paint the concept of a chair, building on Joseph Kosuth’s work ‘One and Three Chairs’.

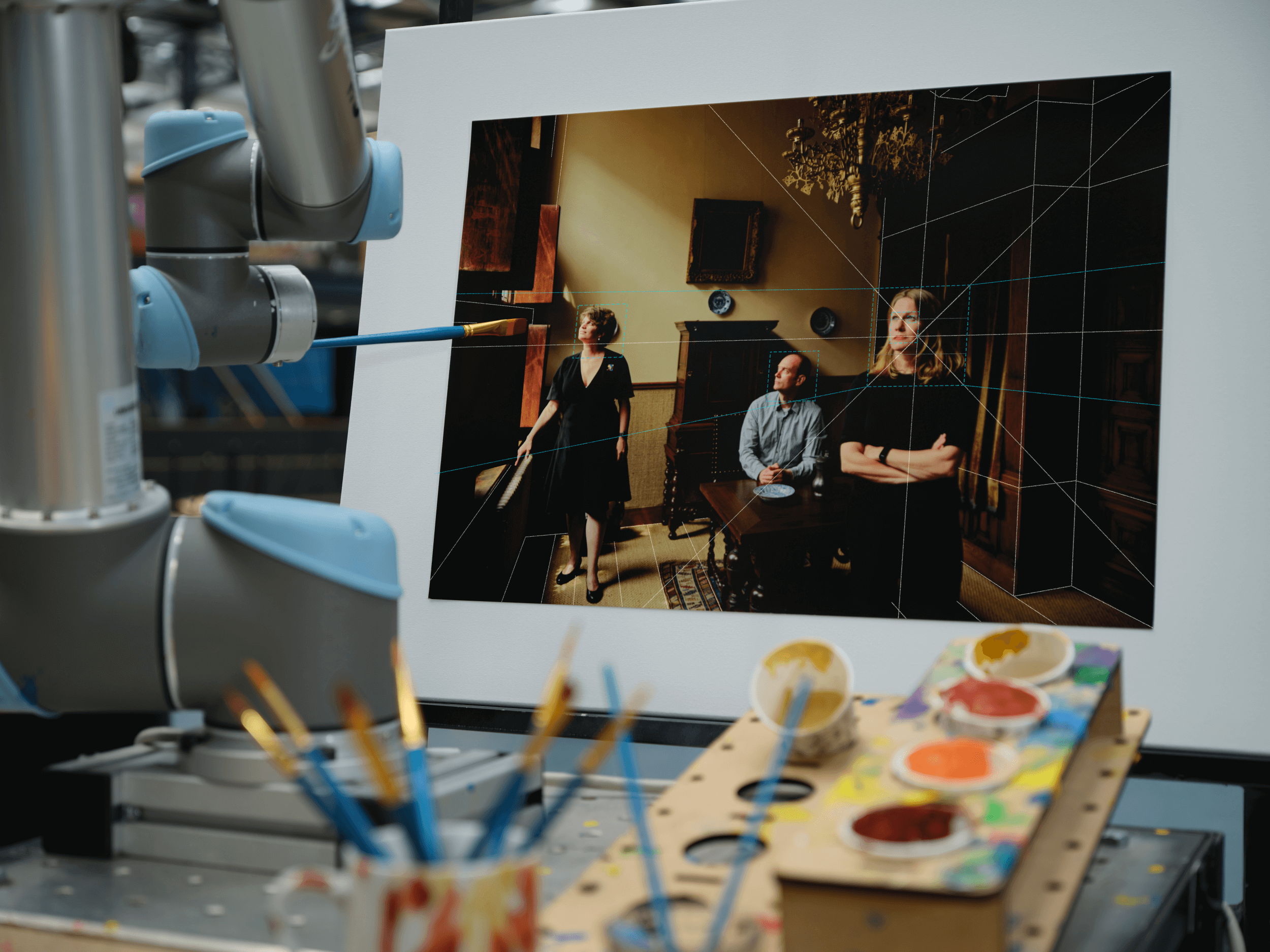

Some of these practice works were offered for sale during an exhibition in a gallery in Würzburg, under the title Bob Rob Awesome Robot Art. Van Middelkoop used the proceeds to invest in a do-it-yourself machine vision kit: an artificially intelligent camera system that will give the robot vision in the near future. Until now, Bob Rob has been unable to see or think about what he has been painting. But Van Middelkoop hopes to give Bob Rob the gift of sight in the near future: “I hope that Bob will get the chance to create a self-portrait at least once.”

Can the painting robot be creative too?

The current Bob Rob project focuses mainly on the technical aspects of the robot’s dexterity. The robot cannot see what he is making, he cannot think about it and he cannot invent anything himself. He has no brain and therefore no creativity of his own. He paints exactly the lines that the computer software tells him to. Yet robot creativity is a flourishing subject of research, all the more so because of the recent sharp increase in the power of artificial intelligence.

The pioneer of research into creativity in a painting robot is the English painter Harold Cohen. He built his own painting robot, AARON, back in 1973 and experimented with it until his death in 2016. Most people who see paintings by AARON cannot tell whether they were painted by a human or a robot. But Cohen used AARON mainly to create new, interesting works together with the robot. And this collaboration with a robot is also what intrigues Aschenbrenner and Van Middelkoop.

In the future, Van Middelkoop would also like to investigate what is possible with Bob Rob in terms of creativity. “Can a robot add value to the creative vision of the maker? Can a robot possibly paint on 3d printed objects that are too complex for humans to paint by hand? Ideally, I hope the robot will help to raise the starting point of human creativity to a higher level. I think craftsmen will continue to be needed, but I think the robot can take their craftsmanship to a higher level.”

Assistant professor Willemijn Elkhuizen, who specialises in 3D printing and scanning, also got involved with the painting robot. The first big job for Bob Rob was to help paint a portrait of Delft professor Jo Geraedts in 2019. Geraedts was retiring, and Elkhuizen, Aschenbrenner and a few colleagues wanted to offer him a farewell painting that would apply all kinds of knowledge emanating from his profession. This portrait was to be a variation on Vincent van Gogh’s painting ‘Portrait of Joseph Roulin’, which hangs in the Kröller-Müller Museum.

Elkhuizen: “I thought there was a strong resemblance between professor Geraedts and Roulin, and that’s how the idea arose to have Bob Rob co-paint a portrait of Geraedts. That new painting was eventually created in close cooperation between human and robot. Bob Rob took care of the coarser lines, while Doris painted in the details.”

Some time later, Elkhuizen was looking for an assignment for her students for the bachelor programme ‘Advanced Prototyping’. “Suddenly a number of pieces of the jigsaw came together,” Elkhuizen says. “I was in touch with the company Royal Delft - the last remaining producer of Delft Blue from the 17th century. I was in contact with designer Maaike Roozenburg, who has a lot of experience with ceramics. And I was in contact with Doris Aschenbrenner about what more we might do with Bob Rob. I wanted to bring these three contacts together. Couldn’t Bob Rob paint Delft Blue ceramic, I wondered at the time?”

Bob Rob specialises in Delft Blue

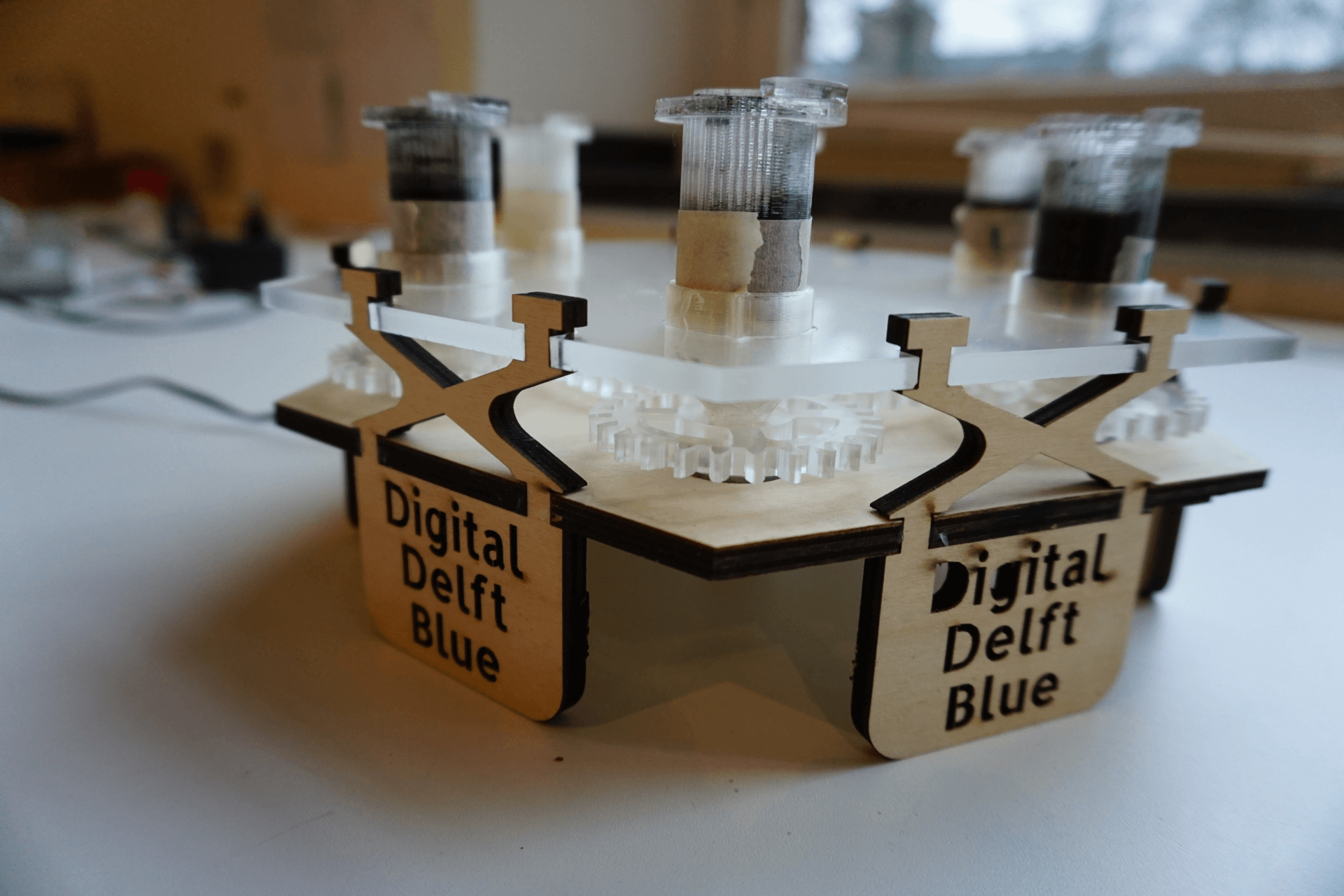

In November 2020, five TU Delft bachelor students - Tiuri Hartog, Sterre Witlox, Midas Zegers, Lieneke Cazemier and Lennart Krieg - started their prototyping project Digital Delft Blue, which was completed in January this year. Led by Willemijn Elkhuizen, Sander Minnoye and designer Maaike Roozenburg, the students investigated how to make the robot paint as naturally as possible on Delft Blue tiles. They were taught by one of the master painters of Royal Delft and set to work with the paint robot. After just a few months, this resulted in tiles with stylised images of ‘The Goldfinch’ by Carel Fabritius, ‘Starry Night' by Vincent van Gogh, and ‘View of Delft’ and ‘The Girl with the Pearl Earring’, both by Johannes Vermeer.

Head of Design Joffrey Walonker supervised the students from the Royal Delft company. He himself once graduated as an industrial designer in Delft. “We were just curious about how far a robot can come in matching a master painter,” Walonker says. “In our company, it takes eight years for a talented painter to reach his top level in painting on Delft Blue pottery. What could a robot do in a few months?”

Royal Delft currently has two Delft Blue product lines: a completely hand-painted line in limited numbers, which is quite expensive, and a cheaper line in which scenes are printed on tiles, plates and other objects as a kind of screen printing. The robot’s results are in between, says Walonker. “The intention of the robot is to make exactly the same thing every time, but because the conditions of, for example, the paint are different every time, the end product is different every time. In the future I would like to develop a new robot line in our products, if it is commercially feasible.”

Bob Rob is far from achieving the level of master painter, and that was not to be expected, but the robot has reached a point where a practical application for Royal Delft is definitely in sight, Walonker explains. “Part of our painting work is to set out a line pattern that puts a certain image in rough contours. A human painter then paints over this. We do this to ensure that products with the same image do not deviate too much from each other. The students have shown that the robot can draw these lines very accurately. In the short term, I can therefore imagine a future in which the robot plays a supportive role in our production process: it can draw exactly the same lines on each tile.”

Walonker explains that technological innovation is of great importance to the company, founded in 1653 as De Porceleyne Fles, and that the link with TU Delft has always been important in this regard. As early as the end of the 19th century, Adolf le Comte, professor of ornamental technology at the Faculty of Architecture, shared his knowledge with the company and even became its artistic director.

Walonker: “We are constantly looking for technical tools with which we can continue to innovate. For example, we are now using digital projections to paint on very large tableaux, something that did not exist twenty years ago. The robot could be the next innovation. Personally, I love to combine innovation with design and craftsmanship.”

Royal Delft will soon start building a museum hall. Walonker would very much like to exhibit Bob Rob as a prototype in it. “I want to bring people into contact with both crafts and technology. If the price tag allows it, I can imagine Bob Rob becoming a kind of robot-artist-in-residence in our museum.”

Willemijn Elkhuizen

- +31 15 27 81041

- w.s.elkhuizen@tudelft.nl

-

Room 32-B-3-220

"One must work and dare if one really wants to live."

Joris van Dam

- +31 15 27 86870

- j.j.f.vandam@tudelft.nl

-

Room B-0-080

Present on: Mon-Tue-Wed-Thu-Fri

“To condense fact from the vapor of nuance” - Snowcrash, Neal Stephenson

Doris Aschenbrenner

- +31 (0)15 27 89523

- d.aschenbrenner@tudelft.nl

-

Room B-3-220

Available on: Mon-Tue-Wed-Thu-Fri

"There are 10 types of people in this world, those who understand binary and those who don't"