Residents of IJburg were keen to participate in sustainable development of the new urban district of Strandeiland. How should they approach this in practice? Els Leclercq and Mo Smit offered them some guiding principles with the ‘Value Flower Model’ and ‘Value Flower Field Maps’, the results of their ‘Waardevolle Wijken’ research into exemplary case-studies of community-based circularity initiatives on the scale of neighbourhoods and urban districts. Els: “The residents were enthusiastic about the visual translation of the total process of a circularity initiative. ‘I can finally explain to civil servants what we're doing,’ one of them said to me.”

Strandeiland is the latest urban island of the IJburg archipelago in Amsterdam, and the intention is to develop this new area into a sustainable, circular functioning district. A group of IJburg residents have formed Stichting Natuurlijk IJburg (the Natural IJburg Foundation) and are investigating how flows of resources, such as water, energy and waste, can be closed as locally as possible while creating added value for Strandeiland at large. In their view, this is the only way in which this area can be truly sustainable. Since the residents have little knowledge of circular area development they asked urban designer Els Leclercq (researcher at the Faculty of Architecture and the Built Environment) to help them consider how they could close the loops of resource flows on the island. Together with her colleague and architect Mo Smit, who is a researcher and lecturer at the Faculty of Architecture and the Built Environment, Els decided to help the residents by making the process as transparent as possible and developing a method based on experience gained from community-based circularity initiatives elsewhere in the Netherlands. Els and Mo have known each other since they were students and they have a common passion for sustainability. Els designs and conducts research into sustainable cities, focusing on processes for circular area development in which new forms of co-operation between various actors are tested. The objective of these cooperative processes is to achieve societal and social added value through closing resource loops. Mo's interest is regional architecture, more specifically the development of circular (self)building methods using locally harvested natural materials.

Six pioneering projects as examples

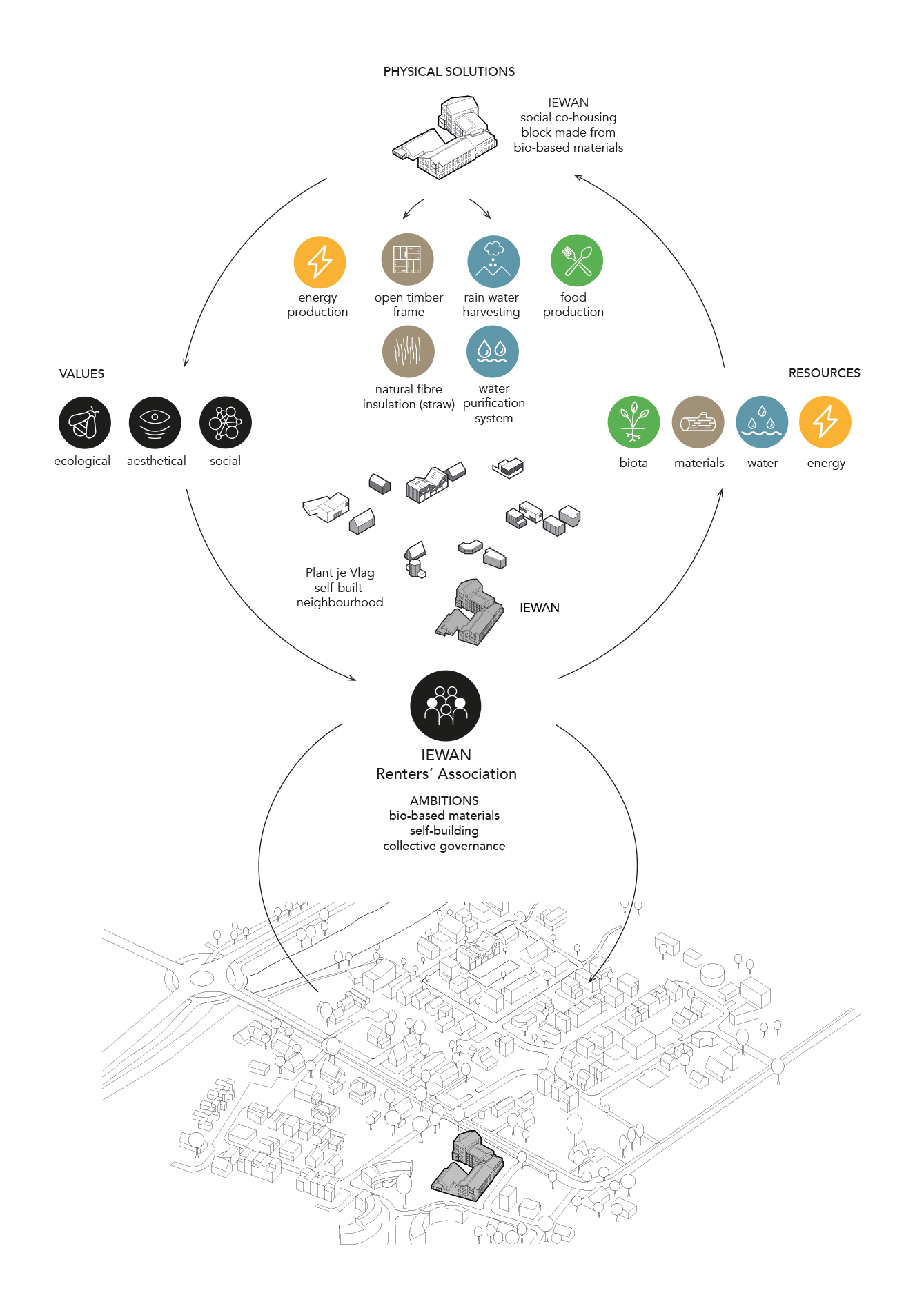

The researchers analysed six examples of community-based circularity projects on neighbourhood level . These include waste separation and processing at the Afrikaandermarkt in Rotterdam, construction of straw-bale houses for the social rental market, and a neighbourhood installation company in Delfshaven, also in Rotterdam, that trains local people and helps accelerate the energy transition in the neighbourhood. “These initiatives were developed by citizens themselves and each of them illustrates a different collaborative process with other parties. Besides this, theses cases are pioneering projects that have led to improved neighbourhood cohesion,” is how Els explains their choice.

“We analysed how these projects had come about and described this process from the residents’ point of view. We made an overview of the parties involved in the collaborations, and to what extent the initial ambitions were ultimately achieved. We also named the issues and challenges that the residents faced , because we consider it important to show that initiatives such as these require a lot of effort.”

It transpires that citizens often put forward useful initiatives and that they organise themselves very well. Els: “They are good at collaborating when common interests and cohesion are at stake, but the subsequent process often takes a long time, years even.” That is difficult to sustain, Mo says: “Many initiatives struggled as municipalities have limited experience with community-based development and often do not know yet how closing resource loops can add value to the neighbourhood.” Els adds that local social networks, such as groups of active citizens, can act as an excellent link between public authorities and citizens, but that as yet municipalities are not making enough use this.

ValueFlower Model and Value Flower Field Maps

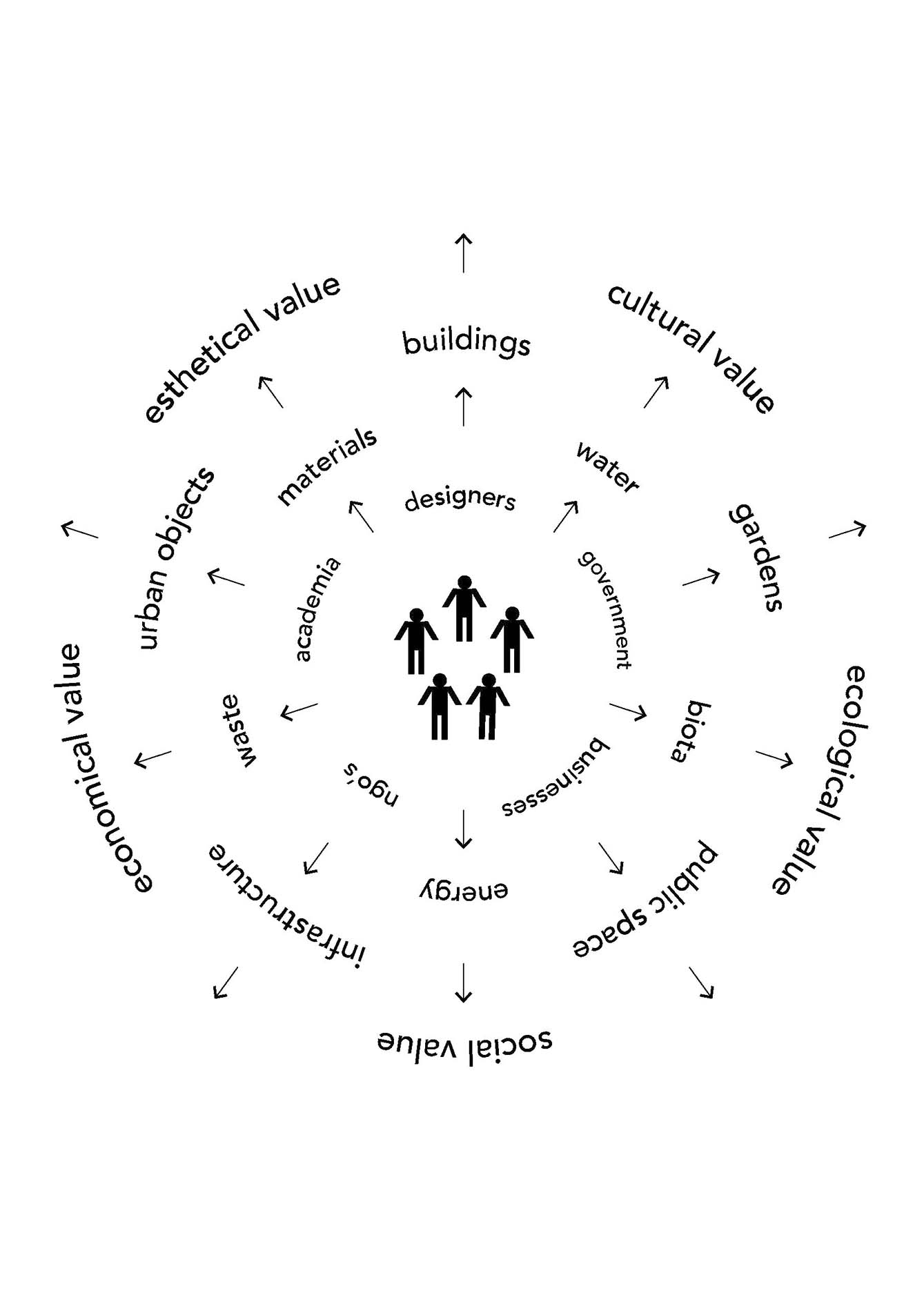

Circularity can be achieved by smartly choosing the right scale for closing resource flows, at individual dwelling level, neighbourhood level, city level and / or regional level) “This is a complex totality that we had to unravel and simplify into a model with which citizens can make sense of circular initiatives,” is how Mo explains their subsequent approach. They named the model the ‘Value Flower’: it is a diagram with the residents in the middle, surrounded by other participants, raw material cycles (water, energy, waste, biota and building materials), spatial elements (buildings, gardens, public spaces, urban objects and infrastructure) and values (ecological, economical, social, cultural, aesthetical value). The Value Flower Model is used to map out the ambitions, spatial interventions and values of the six case-study projects.

The six projects are presented in clear diagrams, the ‘Value Flower Field Maps’ which allow you to see the process and the dependencies among the parties at a glance. These diagrams, too, can be filled in by active residents themselves. Els: “The IJburg residents were enthusiastic about them. ‘I can finally explain to civil servants what we're doing,’ one of them said to me.”

What this means for Strandeiland

What has this research yielded for the residents behind Stichting Natuurlijk IJburg in concrete terms? Els: “The urban design plan for Strandeiland included mobility hubs for parking and transport. At a very early stage, the IJburg residents involved suggested that these hubs be given a much broader function. We investigated this wish using the Value Flower Model, and this resulted in the idea of neighbourhood hubs, which might involve a social programme, such as a community centre or flexible working spaces, in addition to transport. Additionally, these hubs must showcase sustainable and circular construction solutions. These ideas are now being further developed within the framework of a broader participation process, and the municipality will include these results in the schedule of requirements for the neighbourhood hubs.”

The researchers have also taught the residents that the design of circular systems and the management of raw material flows each need their own process. Mo: “The value chains for water, energy and green flows differ from flows for building materials.”

The proposed approach has also yielded a number of recommendations to municipalities. As circular neighbourhood projects involve integrated processes, the researchers feel it is important that municipalities create more transparency for citizens. Els and Mo consider it important that municipalities collaborate with citizens in closing resource loops to create valuable neighbourhoods. As the new Environment and Planning Act (Omgevingswet) gives citizens more options to participate in the development of their own living environment, there will be more opportunities to develop community-based circularity initiatives.

The project was financed by the ‘Design and Government’ academic research programme (TU Delft, TU/e and Wageningen University and Research), part of the Dutch government's ‘Action Agenda on Spatial Design 2017-2020 Working together on the strength of design’.

This story is published: September 2021

More information

- Report 'Waardevolle wijken' (in Dutch)

Dr.ir. Els Leclercq