On a hot, windless day, a leafy neighbourhood may feel 10 to 15°C cooler than an urban area that is more exposed to the sun. Trees thus play a key role in preventing heat stress and the design of climate-proof and healthier cities. “Although we already understand a great deal about the performance of tree species in the built environment, there is very little empirical knowledge about their cooling capacity.”, says researcher Lotte Dijkstra. In order to determine how physical properties such as the trunk and crown shape and the leaf characteristics influence the local air temperature the research team designed and built special ‘climate arboreta’ with sensors installed in each of the 75 tree species.

Trees provide all kinds of ecosystem services, such as converting CO2 into carbohydrates, producing oxygen, and purifying the air by trapping particulates. They provide habitats for fungi, mosses, insects, mammals and birds and so form the basis of all ecosystems, including in urban areas. But trees also help to keep city squares, streets and buildings cooler. Their leaves absorb solar radiation, transpire water and create shade, so lowering the temperature in their immediate environment. During a heat wave, a dense foliage provides much-needed shelter and a park or public garden with lots of trees quickly feels like an oasis in the urban desert. On a hot, windless day, a leafy neighbourhood may well feel 10 to 15°C cooler than an urban area that is more exposed to the sun, which can be enough to prevent heat stress. Trees thus play a key role in the design of climate-proof and healthier cities.

Cooling capacity

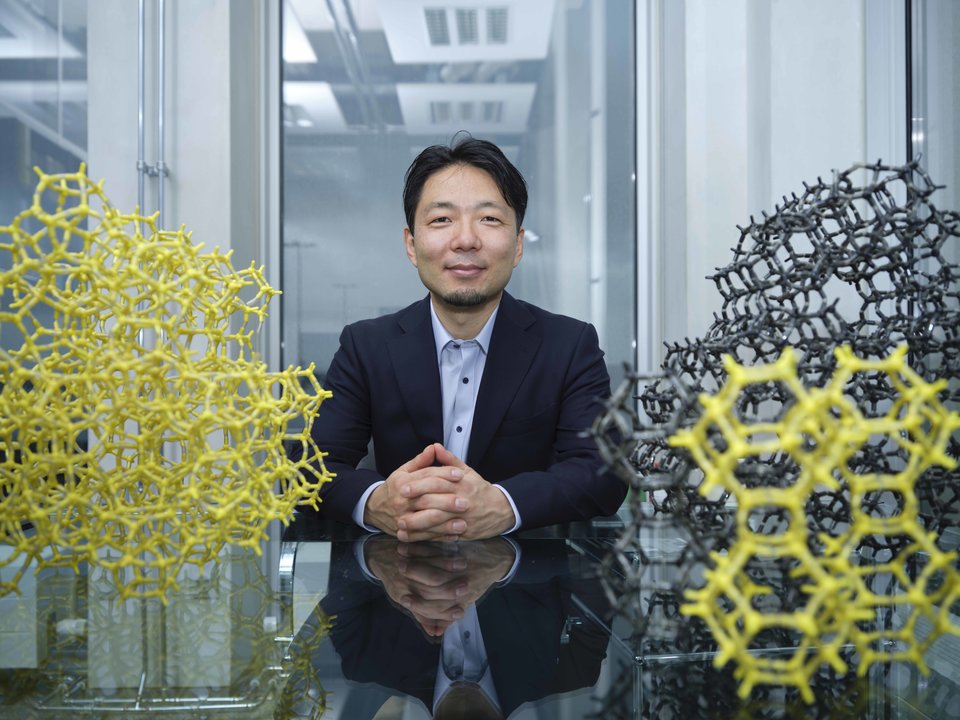

To determine the cooling performance of various species of trees, in 2018 TU Delft’s Faculty of Architecture and the Built Environment and the Dutch Association of Landscape Gardeners (VHG) formed the Urban Forestry joint research programme to support fundamental research into the relationship between tree architecture and the urban microclimate. Urban landscape specialist René van der Velde, who is affiliated with the Faculty’s Chair of Landscape Architecture, is leading the programme. Lotte Dijkstra joined the programme as a researcher. “I have been studying the role of trees in the cities of the past and the present as part of my degree programme in Landscape Architecture,” she says. “My graduation research focusses on the functions of tree avenues in road design. Although gardeners and other ‘green’ professionals already understand a great deal about the performance of tree species in the built environment, there is very little empirical knowledge about their cooling capacity. Consequently, the effects we talk about are only estimates, based on assumptions.”

Field lab

In order to determine how physical properties such as the trunk and crown shape, the branch structure, and the leaf characteristics influence the local air temperature and the apparent temperature, this spring the research team designed and built special ‘climate arboreta’, experimental plots containing tree species that are common in Dutch parks and gardens. “We started by classifying the species by shape,” she says. The team identified 53 basic models, or types. “The resulting classification, ranging from long and narrow crowns to short and wide crowns, can be viewed on the forecourt of the Faculty of Architecture and the Built Environment.”

But how can you use an arboretum as a field lab? A weather station that measures various meteorological values has been set up on an area of the forecourt without trees. The measurements will form the reference values for the measurements made by the sensors placed in the trees, not all of which have been installed yet. “During the meteorological summer, from 21 March to 21 September, we are measuring the air and radiation temperature, humidity and evaporation on warm days,” Dijkstra explains. It is proving difficult to accurately measure the radiation temperature while also taking into account the reflection of solar heat by the buildings and pavements. “These measurements have to be made in the shadow,” she says. “But shadows move, both during the day and throughout the seasons. We are still trying to figure out how to measure this efficiently for so many trees. It is truly experimental research; we are trying things out and learning by doing.” What they cannot do this year they will try again next year. “The experimental plot will remain in place for three years, so we have some leeway.”

Mirror, mirror

Not unimportantly, the arboretum in Delft is one of four such experimental plots. There are mirror set-ups with exactly the same tree species in Almere and Dordrecht, and a slightly smaller plot has been established on a business park in Barendrecht. All the trees are monitored in the same way. “But the conditions are different,” explains Dijkstra. “In Delft the trees are planted in crates and surrounded by buildings, while in Almere they have been planted in the soil and in a greener environment. This allows us to build four separate datasets and compare the results. We want to learn how and how much each species of tree provides cooling under differing physical and climatic conditions. That is truly new knowledge.”

The participating municipalities are helping to fund the research and also provided the plots of land for the arboreta. “Municipalities are looking for practical knowledge that can help them to make their neighbourhoods climate proof and pleasant and healthy to live in,” Dijkstra continues. “Moreover, they are looking for measures that are not too complicated and not too expensive. Making urban areas greener can meet this need. But what type of greenery works best and where should it be planted?” Trees and plants can only be given the space they require – literally and figuratively – if their functions and benefits have been accurately quantified. Greenery often loses out against other functions such as housing and mobility in the competition for the scarce remaining urban space. “Everyone instinctively understands that urban greenery is beneficial in all sorts of ways and that it is becoming increasingly important, but you can’t base policy on instinct,” she explains.

Selection

The research in the arboreta will provide knowledge about the cooling capacity of various shapes of tree. “If one type provides half a degree less cooling than other types, it does not really matter which you choose. But if the difference is 4 or even 8°C, then urban planners will be able to use this knowledge to select the right greenery to help cool neighbourhoods during hot summers. It may even turn out that certain species of trees should actually be avoided because they don’t help towards climate adaptation.” It gets even more interesting when, after selecting for species with good cooling characteristics, you can go on to select for characteristics such as drought resistance or small root systems that take up little space in the soil. “Then you’re killing two birds with one stone,” says the researcher. Several municipalities have expressed interest in the concept of temporary and relatively simple-to-plant urban forests. “You can use our ‘temporary arboretum kit’ to create a mobile green space that offers cooling and enhances the quality of a neighbourhood. And why wouldn’t you? When the neighbourhood is ready, you can plant the trees in the ground.”

More information about the Urban Forestry research fellowship can be found here.

Teamwork

All in all, it is quite an operation. “We are really working as a team,” says Dijkstra. “The team members include colleagues from the Landscape Architecture section and other university staff.” The Campus and Real Estate & Facility Management (CRE&FM) department manages the site and takes care of the maintenance of the Delft arboretum. “CRE&FM will get the trees when the research is completed and plant them on campus.” Microclimate expert Marjolein Pijpers-van Esch, who is affiliated with the Chair of Environmental Technology & Design, is jointly responsible for the monitoring programme. “TU Delft’s Climate Institute helped with the weather station reference measurements,” continues Dijkstra. A microbiologist from the Botanical Garden monitors the soil suitable for the trees, and the researchers designed the wooden crates in which the trees are placed themselves. “We wanted a crate that was durable, easy to assemble and could also function as a bench.” In addition to the aforementioned municipalities, dendrologist Jaap Smit and Wageningen University & Research are also contributing to the programme. Enthusiastic volunteers are helping to manage the arboreta in the other cities. “We are really grateful for their help,” concludes Dijkstra.

More stories