Project DOMO

Project DOMO

Minor International Entrepreneurship & Development 2017

Location

Central River Region, The Gambia

Students

Irene Schmidt

Lisanne Meijer

Youri Penders

External Links

www.projectdomo.ga

https://www.facebook.com/domo.contact/

https://www.instagram.com/projectdomo/

Gambia is a country in West-Africa with sub-tropical climate including a wet and dry season. Its economy is small and based mostly on agriculture tourism and remittances. 56% percent of the land is used for agricultural purposes but because of its climate, these lands are very vulnerable to weather extremes. Because Gambian agriculture is very dependent on rain, droughts and floods could severely impact the food supplies of local farmers. This is very troubling, as 70% of the population are subsistence farmers who only cultivate foods for personal provision. Due to these weather shocks, which have been increasingly worse since weather extremes in 2011 and 2013, 25% of the population is critically malnourished. The poverty in the Gambia is stressed even more when mentioned that the average Gambian lives off less than $1.25 a day.

As a result of the custom of subsistence farming, Gambian locals tend to have secure food supplies during the harvesting months of November until March, which simultaneously houses the dry season, but when the wet season starts, supplies tend to run low and food insecurity increases. Most endure these times by solely eating rice, but this does not nourish the body enough to battle the accompanying problem of malnutrition.

Food insecurity and malnutrition remain to be the foremost problems of rural Gambia, which we plan to solve with a solar dryer. A solar dryer is an active construction that dries and dehydrates fruits and vegetables more efficiently and sanitary than drying foods in the open sun. Dried produce is a great solution to the problems at hand, because it provides the option of conservation. Preserving foods could battle the hunger that must be overcome during the lean seasons. Not only that, but dried fruits and vegetables are nutritious; they contain many fibres, which Gambian food usually lacks. A third additional problem in the Gambia is the lack of entrepreneurship. A new product naturally delivers new market opportunities. As a supplementary objective, we hope to encourage the entrepreneurial skills with the use of the solar dryer.

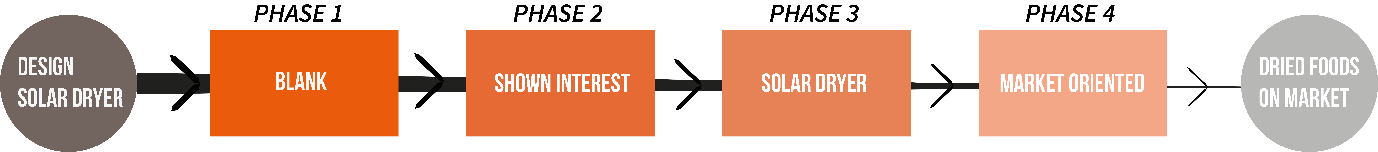

In 2016, a team of students have already travelled to the Gambia to work on project DOMO and build a solar dryer in a local village called Jakaba. The current design is working sufficiently and almost fully consists of local materials. On account of the continuity of the project, optimizing the design of last year is not the current priority, but the aim lies with the implementation of the technology into society. To successfully continue the project, we’ve established four phases related to awareness and implementation of solar drying technology in which a village can exist. The first phase consists of a village who has no knowledge whatsoever about solar drying. Phase 2 contains a village which has shown interest in solar drying. A phase 3 village already has a working prototype within their community which is being used by the inhabitants (for example Jakaba). Phase 4 includes the involvement of the market, where the dried products are being sold and traded to make a profit. These phases have been established to research the gap between a prototype and a market-oriented product and also to explore the possibilities of expanding the solar drying technology throughout the whole country.

We will travel to a few villages which all exist in a different ‘phase’. Documenting all of our interactions with the distinctive phases will be a large part of our activities. In our ‘phase 2 village’ named Ndokey, we will construct a new solar dryer and set up a local committee to manage the venture. We will also explore the market possibilities, undertaking a few trials at the local markets e.g. free samples, demonstrations, displayed cooking and a sales competition with students. We hope to create awareness for dried foods and initiate it as a new commodity.

To successfully realize our project, we will have to account for a few stakeholders. Some of these include the communities of the village and the prospective committees. We will get into contact with the village and its alkalo (village chief) through our contractor. Other stakeholders include a local secondary school, where we plan to teach about solar drying and entrepreneurship; suppliers of materials for building the construction; and financial sponsors. The school is an important partner as the students assisted in building the previous solar dryer and more importantly, they possess more knowledge about Gambian markets than we do, so we can learn from them as well.

Some risks are associated with the progress and continuation of the project. Language and cultural barriers could influence the process, but more importantly, the finalized solar dryer could be abandoned. The locals could see it as something not of their own, but something that has been donated to them. Also, they might not possess the required knowledge about reparation or maintenance leaving the solar dryer deserted. To prevent these risks, we wish to involve the community and its people as much as possible in the building process for them to acquire the proper technical skills and knowledge. Confidently, their investments will contribute to their sense of property over the solar dryer and take appropriate care for it.

In the end, we wish to explore the possibilities regarding expansion throughout the Gambia and research the sustainability of the concept of a ‘solar dryer’. One of the deliverables, next to the documentation of all phases, and the construction of a solar dryer, will be to deduce a sustaining forward path and conclude some future recommendations. The committees set up will however continue to manage the existing solar dryers and increase food security, decrease malnutrition and promote entrepreneurship in the Gambia.

Evaluation

In November 2017, a group of students from the Delft, University of Technology travelled to the Gambia to carry out a project concerning commercial solar drying of fruits and vegetables for preservation and entrepreneurship. A solar dryer provides a method for preserving harvests that could therefore be consumed during periods when harvests are low and a diversity of food is scarce. This would remove the need for immediate consumption when crops are cultivated and would put improve not only food security during the entire year, but also reduce malnutrition. When properly implemented, a solar dryer could also be used as a means for producing revenue. Dried agricultural produce would potentially be of high demand when the original fresh crop would be unavailable. To investigate whether a solar dryer would suit the needs of the local people and to what extent a solar dryer could contribute to development, the group of students travelled to the Gambia and explored this issue. An important question that was also set out to be answered is if a solar dryer could be implemented in a sustainable manner and if continuity is realistic without the involvement of Western initiatives.

Part of the research consisted of constructing a solar dryer in a local family-based village named Ndokey. This process started with acquaintances with the residents of the village. Meetings were scheduled and plans were made for concerns such as location of the dryer, communication and other logistics. One of these meetings involved an excursion to a nearby village called Jakaba. Project DOMO has been very active in Jakaba in the winter of 2016 whereby a large solar dryer had been built and the people were instructed on the use and functionality of the solar dryer. Connecting the people of both villages with each other has had a valuable influence, and the people of Ndokey received a visual and interactive understanding about solar dryer. Accordingly, no false assumptions were made beforehand and the transfer of information happened without any lingual or cultural barrier.

The subsequent building process happened in collaboration with the occasional villager and was completed in about twelve days. Following the completion of the solar dryer, a proper knowledge transfer was executed, which included both building and user manuals and a handful of demonstrations with drying of vegetables and consecutively cooking with dried food.

The solar dryer of Jakaba was evaluated to discover potential improvements and determine if the solar dryer has contributed to the community adequately. After an experimental procedure, the functionality of the solar dryer could be established to be satisfactory, but the frequency of use was revealed to be less than expected. Although the dryer is being utilized, the threshold remains high and often there appear to be no crops to dry.

A visit was also made to Burong and three other neighboring villages. This location was visited to research potential settings which would be suitable for the introduction of a solar dryer. Almost all villages in the Gambia possess a so-called community garden, where a large share of the female residents work to cultivate and grow vegetables during the dry season. Jakaba and Ndokey have a community garden, as do the villages surrounding Burong, which were all visited for the purpose of the project. The visitation revealed that most of these villages suffer from malfunctioning community gardens and are isolated from any large markets. This causes there to be a small amount of excess harvests and the surpluses that do emerge often spoil quickly as the markets cannot be easily reached.

All of these experiences in the different villages which are all situated in a different state of solar drying, have caused four conditions to be formulated for a self-sustaining and profitable solar drying system to be realized.

- Awareness about solar drying and dried fruits and vegetables

- Demand for dried fruits and vegetables

- Surpluses and excess harvest from community gardens

- An easily accessible market

The first condition requires there to exist sufficient awareness about solar drying and dried produce. Without any awareness, there would be no users or customers to purchase these products. This immediately links with the second condition, which insists upon a certain demand. Dried products do have a value proposition. This proposition needs to be exposed and utilized to start generating profit and create a business. The third condition demands there to be excess harvest, because without foods to dry there won’t be dried foods to sell. A key component of this condition is that community gardens will have to function adequately to supply the demand. If the gardens lack certain facilities, then these might have to be addressed before an effective venture can be set up. Finally, a market must be accessible for dried products to be sold. Deprived of an access to a market would not excel any profitability.

Without one of these conditions sufficiently met, a solar dryer could still be contributing to small scale development and improve the lives of the users, but sustainability would be challenging to attain. Certainly, small scale development is incredibly valuable, and merely the acquaintance with a different culture and an alternative way of thinking yields an enormous impact. However, aid from more developed countries cannot continue indefinitely and to reduce the dependency, these conditions

References

Contact CIA. (2016, April 01). Retrieved October 25, 2017, from www.cia.gov/library/publications/the-world-factbook/

Gambia. (n.d.). Retrieved October 24 2017, from www1.wfp.org/countries/gambia

Gründeman, E., Loopik, E., Verbart, J. (2017). Gambia Vegetables Drying.

Human Development Reports. (n.d.). Retrieved October 25, 2017, from hdr.undp.org

World Bank Group - International Development, Poverty, & Sustainability.(n.d.). Retrieved October 25, 2017, from

http://www.worldbank.org/