Igo Boerrigter, master student at the Faculty of Industrial Design Engineering at TU Delft, was commissioned by De Nederlandsche Bank (DNB), the central bank of the Netherlands, to analyse the current use of cash. Based on this analysis he made recommendations for a sustainable, usable and affordable cash system for the future. He also devised a more user-friendly alternative to coins.

The end of cash is in sight, and this could happen sooner than we think. Last year was the first time we paid more with debit card (55%) than with cash (45%) in the Netherlands. This European trend, of which The Netherlands are a frontrunner, is expected to continue. Industrial Design Engineering student Igo Boerrigter researched the future of cash and came to a startling conclusion: “It’s no longer the question if we should move away from cash, but how we’re going to manage this inevitable end. We still have the chance to make right choices, and protect vulnerable groups of people during this transition, but it’s coming closer fast.”

His graduation assignment at the central bank of the Netherlands seemed fairly straightforward: research and analyse cash as a use-product. What can be improved, from a user perspective? What is the future of cash?

Change in perception

In order to understand this user perspective, you map user behaviour. So Igo went out and interviewed people who just paid at shops and other retail establishments. The large number of debit card transactions, or rather, the small number of cash money transactions, surprised him. He discovered a generational gap in the perception of money. Older people largely see cash as the foundation of their finances, and the numbers they see on their bank account as buffer. Younger people, on the other hand, see their ‘digital money’ as their baseline, and cash as ‘extra money’. Increasingly user-friendly apps and payment systems also appear to change the notion of cash giving you a better insight into your personal finances and stimulating better budgeting. Your bank’s app will tell you which expenses you can expect, and can even predict your account balance based on your spending behaviour. Because of these developments in ease-of-use, the shift from cash to digital payments has dramatically increased in pace.

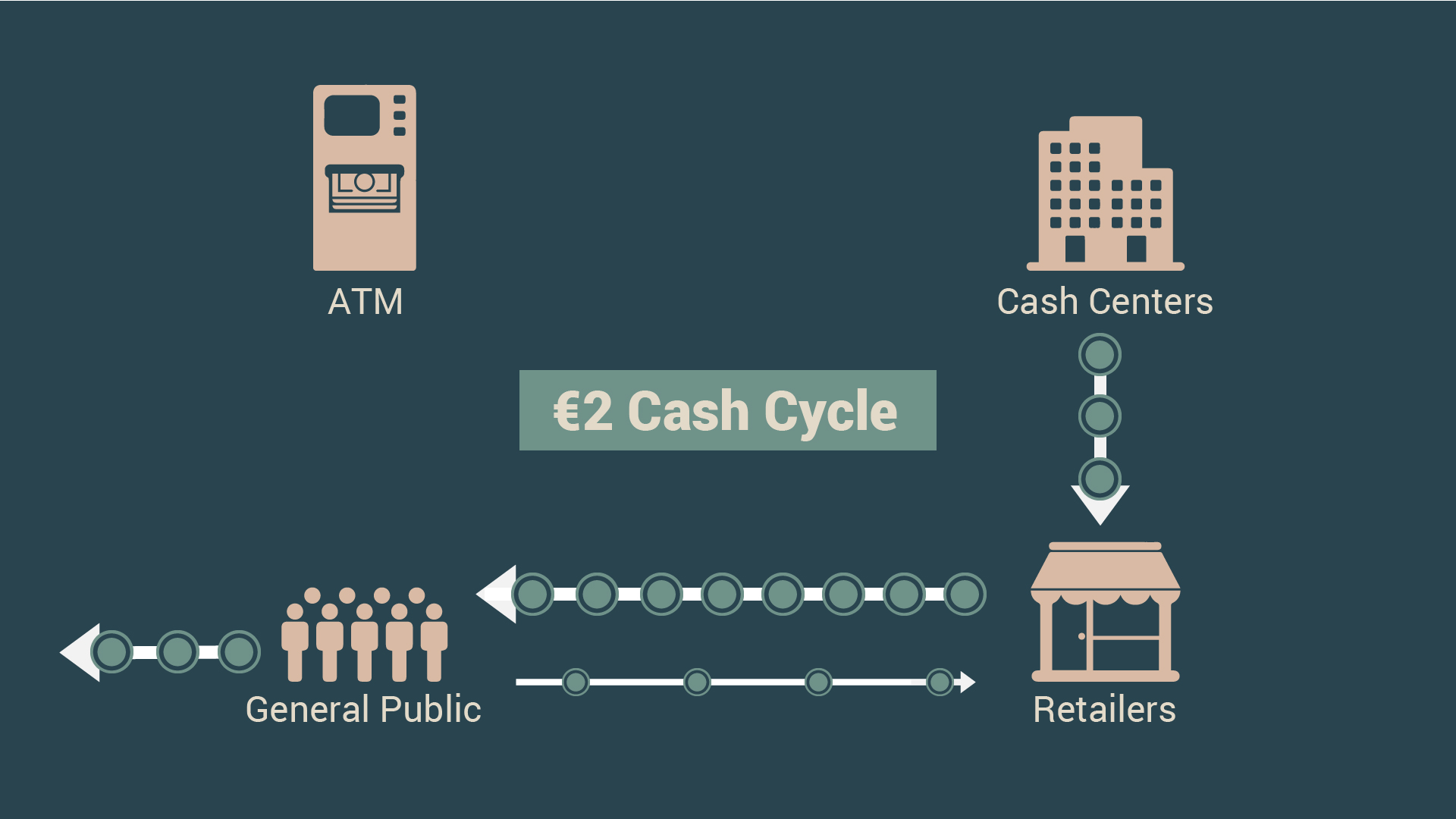

The Circle of Cash

“The use of cash varies per country dependant on digitisation-levels, but the trend is the same everywhere: eventually cash will disappear from the economy. In Sweden, cash has practically disappeared in recent years and they are now experiencing problems there,” Igo says. In the Netherlands, shops, but also government services like town halls, are increasingly no longer accepting cash. The shrinking size of the cash economy is driving up the costs for the remaining users. Last year, Dutch banks announced they will start working together in the shared ‘Geldmaat’ ATM machine, reducing the costs of maintaining their own ATM network. Early in 2019, the largest cash distributer of The Netherlands (SecurCash) filed for bankruptcy.

Research and analysis at the central bank of the Netherlands showed that this trend is expected to continue. Eventually, we’ll reach a point where usage of cash has decreased by so much, that maintaining the infrastructure for cash distribution and the ATM network will no longer be possible. Cash will disappear. In other words: cash will soon become too expensive. This could cause significant problems for the vulnerable groups in our society for whom the march of digitisation is moving too fast: the elderly, low literate and cognitively disabled. Another set of risks relate to large-scale crises, such as flooding, when the economy cannot fall back on cash money as means of transaction. Lastly, it would mean losing the tool that allows people to own and control their own money independently of commercial banks.

For his graduation thesis Igo analysed, among other things, what happens to banknotes and coins, and the road they travel. “The journey of 50 euro notes is particularly interesting: these banknotes come from the cash dispenser, are spent in shops and then go back to the bank and back to the cash dispenser. They make that same trip over and over, and hardly go back and forth between consumer and retailer. That is very expensive to maintain.” Something similar happens with coins. “They go from the bank to the shopkeeper, who gives them to the consumer as change. A small part of the coins then goes back and forth between the consumer and the shopkeeper, but a large part disappears into drawers and jars. That too is very expensive, because shops have to bring in new and heavy coins all the time.”

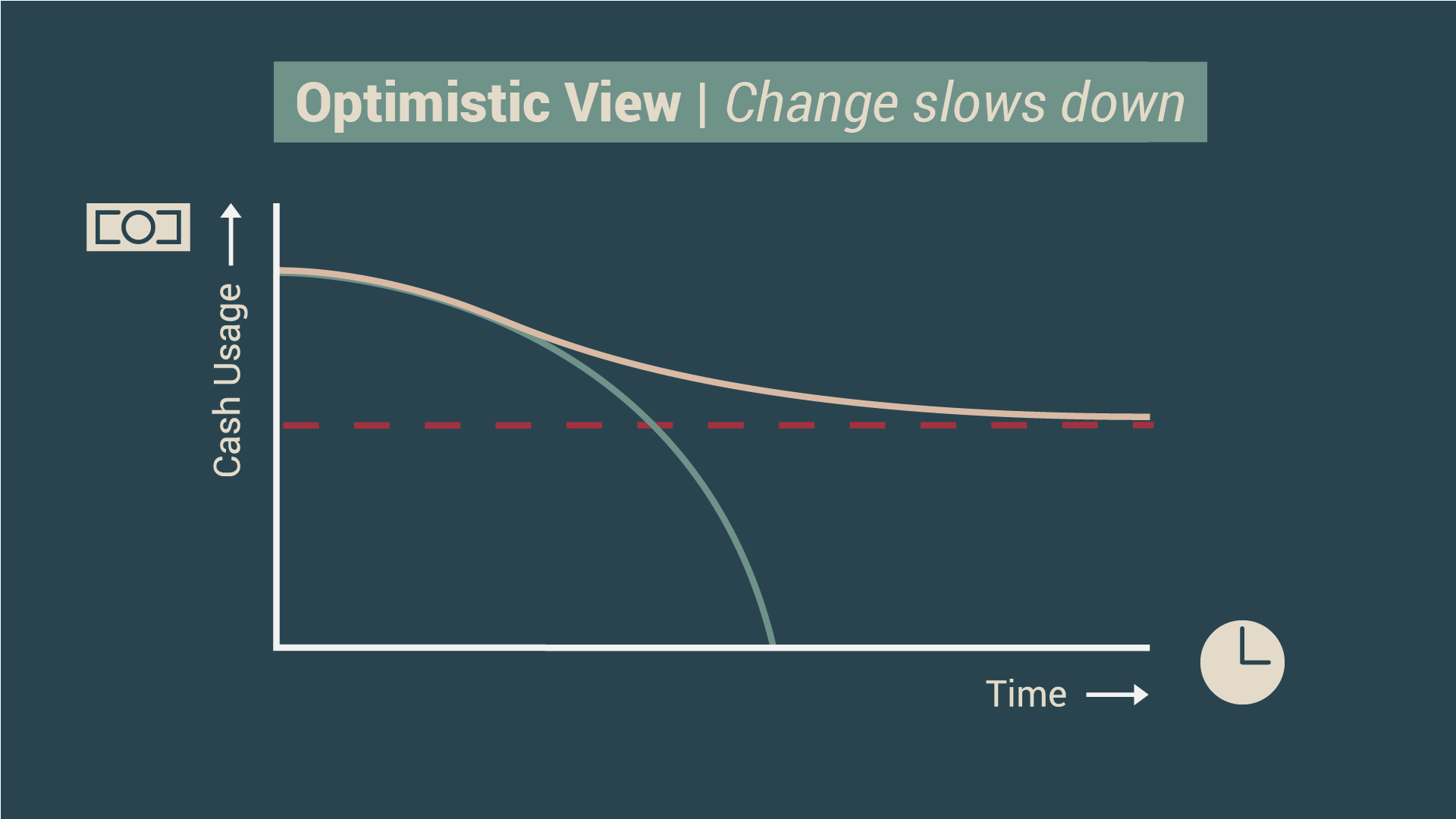

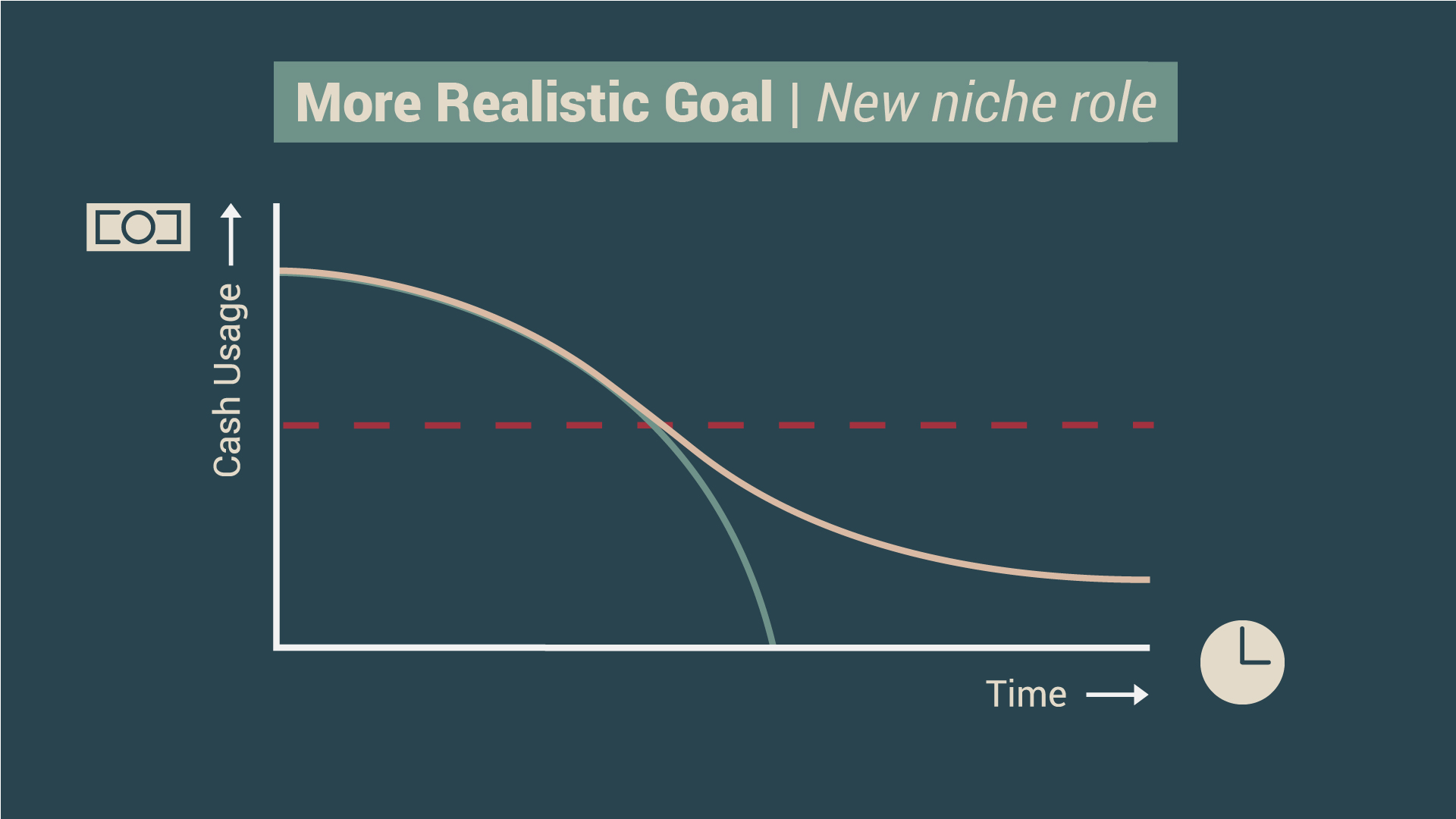

Bringing the future closer

“We’ve got three possible future scenario’s ahead of us”, Igo says. “Option one: we do nothing and let cash money ‘crash’. If the government doesn’t take action, cash will automatically reach a critical lower limit and simply disappear. People dependent on cash money transactions could get hit hard by this, they won’t be able to buy their groceries.” He continues: “The second option is that, in spite all our analysis and predictions, cash usage does not decrease further. This is more wishful thinking than an actual basis for a strategy. Finally, our best case scenario is that we design a smaller, but much more efficient system to allow cash to continue to exist. This will smoothen the transition to the inevitable full digitisation of money transactions while maintaining a cash system that can function on low use.”

According to Igo, the latter requires two things: banknotes must remain in circulation longer between shopkeeper and consumer, and coins must become more practical so that they too remain in circulation. “In Switzerland, for example, you have an app that facilitates cash withdrawals at shops. You indicate how much cash you want, and the app tells you at which shop you can pick it up. This eliminates the need to pump around banknotes to distributors and ATMs. It does require banknotes that can last a long time, meaning possibly switching from paper to plastic banknotes. It would also mean that shops, perhaps with the help of smart cash boxes, have to check for counterfeit notes themselves, because notes will no longer pass through the Dutch Central Bank or central cash centres.

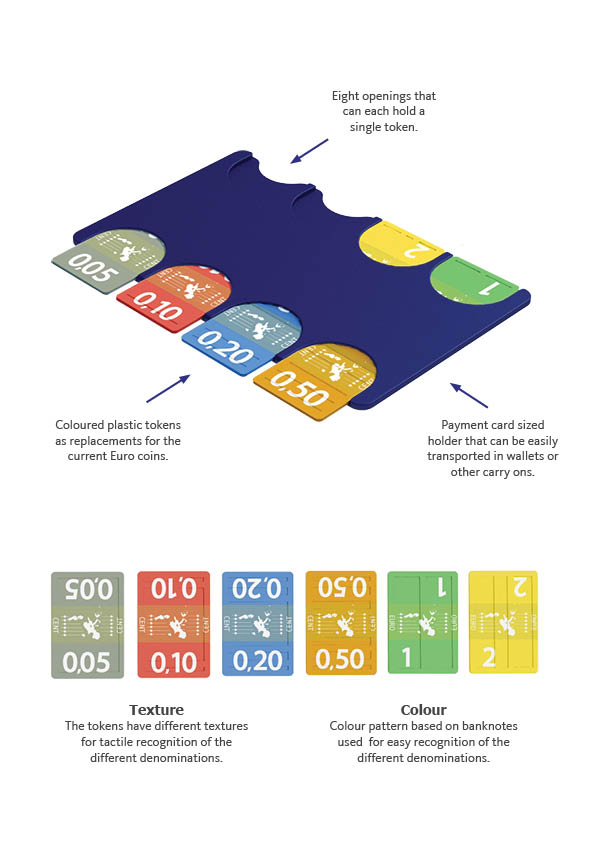

A second part of Igo's redesign of the cash-system concerns the coins. “Currently, people consider coins as cumbersome to transport and use. You can’t see their value right away, they’re heavy and take up a lot of space.

Boerrigter therefore designed coins to suit the modern consumer: his ‘coins’ are brightly coloured ‘chips’ that fit in a holder the size of a credit card. “This way, coins can easily fit into cardholder-wallets that people use more and more. Or in a phone case. The colours make it easy to see what value each coin represents.”. Flipping a coin to make a decision would be a little more difficult, because Igo’s ‘chips’ are made of plastic and look the same on both sides.

Both measures, says Igo, could ensure that maintaining cash money in our society will remain economically viable.

Assistant Professor Jasper van Kuijk:

"Igo’s work fits a broader development we see with the current generation of students who graduate at IDE. Fifty years ago, when the faculty was founded, we trained designers who could create easily mass produced user products. This later expanded to user interfaces and services. The newest class of designers work on complete systems, often with societal impact."

The newest class of designers work on complete systems, often with societal impact.

"It’s great to see how Igo managed to create new insights into the use and future of cash. And how he’s able to connect the user’s perspective, societal needs, business considerations and technology. This integral approach is essential for successful designs."

J. Miedema, Dutch National Bank:

"Current developments surrounding cash are primarily driven by a technology push. At the Dutch national bank (DNB), we aim to make the public, as end-users, the central piece of our cash money policy. Thinking in terms of users is what makes industrial designers unique. We saw this with their work on improving the Dutch public transport ticketing system, for instance. Igo's analyses of the use of cash shifted the way we thought about the topic."

Igo's analyses of the use of cash shifted the way we thought about the topic

"He foresaw three possible future scenarios, each with a different level of use of cash and the changing role we could play as a central bank. When the societal trend of decrease in use of cash continues, how should we adapt our strategies and processes? For one of these scenarios, Igo designed a valuable ‘future concept’, that has the potential to shift the way we all think about cash."

Cash for emergencies

Letting the roles that cash play die out completely also carries large risks, especially in the case of large-scale calamities, according to Igo. “The system behind debit-card payments is heavily dependent on a limited infrastructure. When disruptions occur, people can now still fall back on cash. This will disappear. If the complete infrastructure of cash shrinks, it will not be able to cope the same amount of transactions as debit-card payments. They are barely able to do so now. ATM machines could be empty in minutes.”

This is why he advocates for the government to make sure alternative payment methods are available. For disruptions with a limited duration, other digital systems are an alternative. Dutch payment app 'Tikkie' is an example of this, so are payment systems linked to telephone numbers, as is common in Africa. “For major crisis situations, such as floods or structural problems in the ICT infrastructure, the government will have to draw up an emergency plan, because if the entire digital infrastructure is out of use, then probably the only solution is that the government 'advances' cash to citizens.”