From the house of God to starters’ homes

An architecture student bought a disused church to live in with friends. Then fate struck. Now, four years later, he is creating four starters’ homes from ruins.

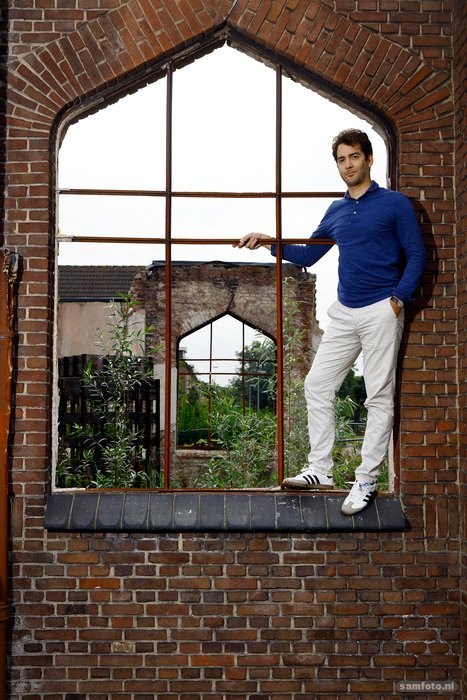

Never waste a good crisis, they say. Architect and TU Delft alumnus Nima Morkoç put that saying into practice when his enormous shelter went up in flames. Everything is now pointing to the burned out Juliana Church on Heijplaat rising from the ashes as four welcoming and affordable starters’ homes. “The biggest task for our generation of architects is to create affordable housing.”

Garden town of Heijplaat

The isolated village of Heijplaat lies in the middle of the Rotterdam port area. After piles of sea containers, villas suddenly appear amidst unexpected greenery. The Courzandseweg, ‘steak lane’ as it is called by the locals, was built for the Director of the RDM and his staff. Behind it is the ‘meatball’ neighbourhood for the labourers.

At its highest point, 3,000 people lived here. Now the population has just about halved. The village was built as a garden town for the personnel of the Rotterdamse Droogdok Maatschappij (RDM, Rotterdam dry dock company). It had everything: homes, schools, shops, a bandstand and three adjacent churches – Catholic, Reformed and Dutch Reformed.

However, the tide turned for RDM, which in its glory days was one of the largest shipyards in Europe. Eventually, in 1983, bankruptcy was inevitable. For the Heijplaat community, that meant unemployment, poverty and the loss of social cohesion. On top of that, increasing secularisation closed the churches in Heijplaat one at a time, including the Dutch Reformed Juliana Church. What had long been a meeting place for the believers in the community had lost its function and was empty.

One chance in a million

Former Architecture and the Built Environment student Nima Morkoç was phoned by his father, who lives in Heijplaat, in spring 2017. The Woonbron housing corporation had put the Juliana Church on the market after 10 years of disuse. Morkoç senior, Nima’s father, convinced his son to buy the Church and the vicarage together – Nima the Church, his father the vicarage.

Four TU Delft Architecture and the Built Environment friends were interested in moving in. The master students would build five tiny houses in the Church to live in. The Church hall would be used for parties, film nights and dinners. There would be space for an art atelier for Nima’s sister Mina. Just before summer, everyone gave notice on their accommodation and moved their belongings to Heijplaat.

NL alert

On Sunday 6 August 2017, Morkoç’s father phoned. “The Church is on fire!” Driving over the Rotterdam Erasmus Bridge Morkoç saw a sea of fire and clouds of smoke billowing across the centre of Rotterdam.

The Rijnmond news website reported on the fire the next day. “Only the stone walls and the Church tower are still standing. The building is a write-off.” Experts concluded that the fire was probably caused by a faulty ventilator.

Despite the grief of the lost personal belongings, a graduation project was landed in Morkoç ‘s lap – finding a new purpose for the burnt down church. What makes the Church a historic building for its surroundings? This is the burning question in Nima Morkoç’s dissertation, Social Monumentality in 2018. The historic significance did not lie in the building itself that Morkoç describes as ‘a barn with the addition of a bell-tower’. Nor, oddly enough, did it lie in the use: ‘the church was empty for 10 years and nobody seemed to care’.

He discovered that there are about 600 disused churches in the Netherlands at present, and that two join the list every week. The empty religious heritage is such an all-encompassing and complicated issue that a special platform (in Dutch) was set up to share knowledge, networks and experiences.

Restoring social connections

The issues around the Juliana Church, now called Project Juul, also apply to other churches: the social the cohesion has disappeared and loneliness is on the rise. The question, and the assignment that Morkoç has given himself, is how can the social monumentality of the Juliana Church be restored so as to benefit Heijplaat? It is about restoring social connections that had disappeared long before the fire broke out.

After 120 versions, Morkoç came up with a design for living space for students and employees from start-ups on the RDM Rotterdam premises. The living spaces are built round the empty space of the Church. Two blocks, one on either side of the clock tower and one on the site of the vicarage. That space, between the old windowless Church walls, will continue to be a meeting place for those living nearby. He earned a seven for his graduation work.

Affordable housing

After graduating, Morkoç started working as an assistant designer at West 8. Last year he moved to Mei architects and planners. He still keeps one day a week free for the redevelopment of the Juliana Church as a project for his own company, HUM Design & Development.

“It became a sort of traineeship in urban development, architecture, landscape architecture, legal affairs, commercial viability and zoning plans,” he says looking back. Before any plans could actually be made, the zoning plan and the leasehold had to be changed, and the Aesthetics Committee had to give its approval. A new purpose for the Church had to meet all these conditions and the end product also had to benefit Heijplaat.

After 23 rejections, at the end of 2019 all the lights turned green for Project Juul. The Aesthetics Committee approved the plan and a year later the contractor BIK Bouw signed the building team agreement. The application for the building permit was submitted last summer.

Morkoç’s strong preference was to repurpose the building into homes. “The biggest task for our generation of architects is to make affordable housing. Everyone I know is finding this difficult.” This naturally was not in line with the repurposing plan of the Church, but there was room for discussion.

The municipality preferred larger and more expensive homes for well-off families, but Morkoç’s choice lay elsewhere. He pushed for a design for four compact (110 m2) and affordable homes (around EUR 400,000) within the contours of the Church. The vicarage, where his father lives, is no longer part of the plan.

Meeting place

The homes are designed for modern life and work. The active part of life takes place on the ground floor – cooking, eating, social interaction and a communal open garden. The first floor is for sleeping, and the second floor has a high and spacious workspace. The windows on the outside are rectangular and sleek, in the Reformed Church style. The windows on the courtyard side are bigger and rounder. There are no hedges and the space between the houses is intended to be a meeting place within the seclusion of the old church walls. The building work will start at the end of this year and is planned to finish at the end of 2022.

Red pointed tower

Anyone squinting at the tower will see the roof of the Juliana Church again with an open groove in the middle. The reconstructed open pointed tower will be covered with a special species of ivy that will colour the pointed tower green. Once a year in autumn, the leaves change colour and the pointed tower will be bathed in red. This is in remembrance of the fire that instigated everything.

At the end of next year when the new residents occupy the homes, the young architect will have achieved a solution for two burning questions in housing and urban issues: empty religious heritage buildings and the need for affordable starters housing. In Morkoç’s experience, “People in architecture want references, something that has already been done. I hope that Project Juul will be a source of inspiration for the hundreds of empty church buildings that people now don’t know what to do with.”

More information: wonenbijjuul.nl