Multidisciplinary engineers needed to tackle rising sea levels

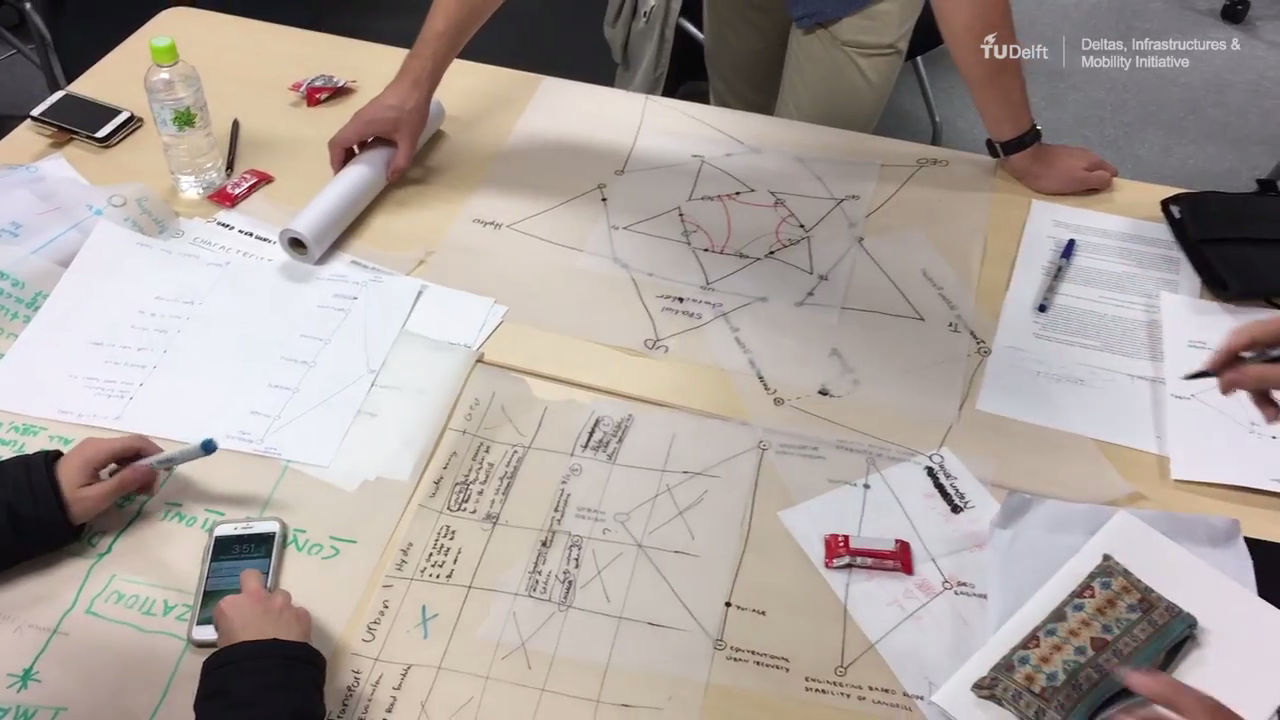

In the Delta Futures Lab, forty Master’s students from different programmes work together on hydraulic engineering and spatial issues.

When the Delta Works were under construction, it was hydraulic engineers who decided which structures needed to be built where and how. Half a century later, we are preparing ourselves for rising sea levels – but engineers no longer have the final say. Measures also need to be multi-purpose: a dyke is not just a sea defence, it also has to fit in with the landscape, have public support, and contribute to a richer ecology. “Complex issues are no longer monodisciplinary,” says lecturer Dr Martine Rutten of the Delta Futures Lab (CEG). “Employers are looking for people who can connect various disciplines.”

Other way of thinking

This need is at the heart of the multidisciplinary network Delta Futures lab, in which the faculties of Civil Engineering and Geosciences, Architecture and the Built Environment, and Technology, Policy and Management work together.

The forty students who started this Master’s programme in July come from these faculties, although the network is open to students from other faculties and from other educational institutions.

“Interfaculty collaborations are becoming more common during the Bachelor’s phase,” says Dr Jos Timmermans (TPM), “but no one has yet integrated various disciplines during the Master’s.” To ensure that engineers don’t “lose depth of knowledge”, participants bring their own thesis supervisor with them. Lecturers at the Delta Futures lab allow students to choose from various hydraulic and spatial issues, and they ensure that different disciplines are represented in each group.

Students are introduced to other ways of thinking and working, and they learn to define their own role in this process. Architecture students like to create beautiful designs, but they might not always consider the feasibility of their design. Civil engineering and TPM students have more of an eye for that. Conversely, civil engineering students sometimes lapse into the design mindset of their predecessors. They come up with a sound design and call it ‘the solution’ without considering social or ecological wishes or requirements. TPM students are happy if the process was good. They share the architect’s holistic view and the civil engineer’s solution-oriented approach. “At first, they are often reluctant to express themselves because they miss the background knowledge.” After a while, they discover that they can actually add value when different disciplines work together, says Timmermans.

The people at the Delta Futures lab call this overarching approach ‘Research by Design’. The designs by architecture students have a strong communicative function. A good design can open up new perspectives and involve people in the great changes that await us,” says Timmermans.

For students, taking part in this Master’s is more than an eye-opening experience. The Delta Futures lab introduces them to consultancies and dredgers from the field, they build up a network with people from different areas of expertise, and they learn to play their part in a diverse team. These are all valuable qualities for engineers who want to protect the delta against rising sea levels.