Three ideas for taming the North Sea

This summer saw the ice on Greenland melt faster than ever before. What will happen if efforts to curb climate change fail? In that case, temperatures in the year 2100 could be 2.5 to 3 degrees higher than before industrialisation. That will cause sea levels to rise by several metres (average of 2.3 m per degree).

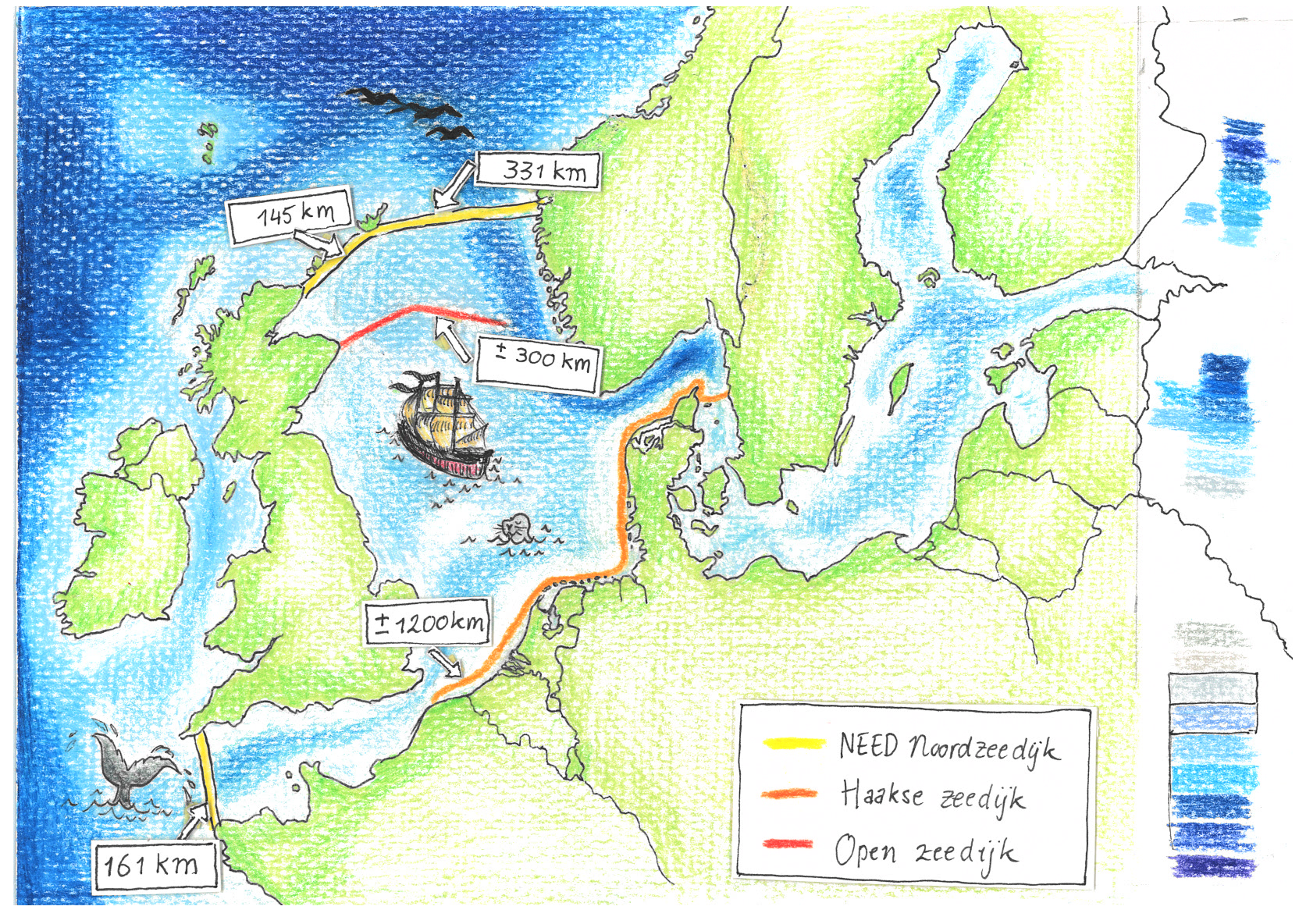

Physical geographer Dr Sjoerd Groeskamp, who works at Utrecht University and the NIOZ (Netherlands Institute for Sea Research), was concerned about the impact on northwest Europe. With his German colleague Joakim Kjellson, he devised a rescue plan: the Northern European Enclosure Dam (NEED) between France, the UK and Norway. ‘NEED may seem over-the-top and unrealistic’, they write. ‘It's one of the greatest ever civil engineering challenges, but it also offers the most effective protection for 25 million Europeans and their important regional economy.’

“A magnificently crazy idea”, is Prof. Peter Herman's view. An ecological engineer (Faculty of CEG), he foresees an environmental disaster because the 30,000 m³ of fresh water flowing into the North Sea every second will transform it into a freshwater North Lake within a century. Deeper oceanic trenches will remain salty, but lacking oxygen and life.

The plan devised by engineers Rob van den Haak (who died in 2019) and Dick Butijn is less intrusive. This plan for De Haakse Zeedijk (DHZ), a sea dyke that Butijn named after his late colleague provides a second coastline. A 3.5 km wide body of sand protrudes 20 m above the current average sea level, 25 km offshore. The European version runs parallel to the North Sea coast for 1,100 km from Calais to northern Denmark and across to the other side (Gothenburg).

Dr Bas Hofland (CEG) sees the DHZ as a “realistic plan” because it takes account of nature, preventing salinisation, and shipping. “It's an integrated plan and one of the potential solutions.” Hydraulic engineer Prof. Wim Uijttewaal appreciates its combined functionality. More than a flood barrier, the dyke also provides opportunities for an airport, drinking water basins and energy generation.

Uijttewaal is even in favour of a semi-open North Sea dam. Dutch dykes are designed to withstand the fiercest conditions: spring tide, wind impoundment and the impact of high waves. According to his calculations, a semi-open dyke from Scotland towards Norway could reduce both the tide (average 1.5 m) and the storm surge by around a metre on the Dutch coast. “Reducing the peaks creates space for a few metres of rising sea level, buying you time”, says Uijttewaal. He envisages the dam slightly further south, where the North Sea is shallower.