The government has growing expectations of citizens when it comes to climate adaptation, but not every citizen or neighbourhood is able to live up to these expectations. Neelke Doorn, Professor of Ethics of Water Engineering, is studying ways of avoiding social divides between neighbourhoods.

What exactly does a Professor of Ethics of Water Engineering do? If Professor Neelke Doorn is asked this question at a party, she will explain it using an example that we all understand. “Residue from medicines in our waste water is a matter of responsibility. But who is responsible: the water industry, the health sector, agriculture? Should we focus solely on the quality of drinking water, or should we purify all our waste water, which is better for the water system and the environment? Or should we perhaps focus on using fewer strong medicines? You’re constantly weighing up all the different values; it’s much more complex than just a technology issue.”

Matter of urgency

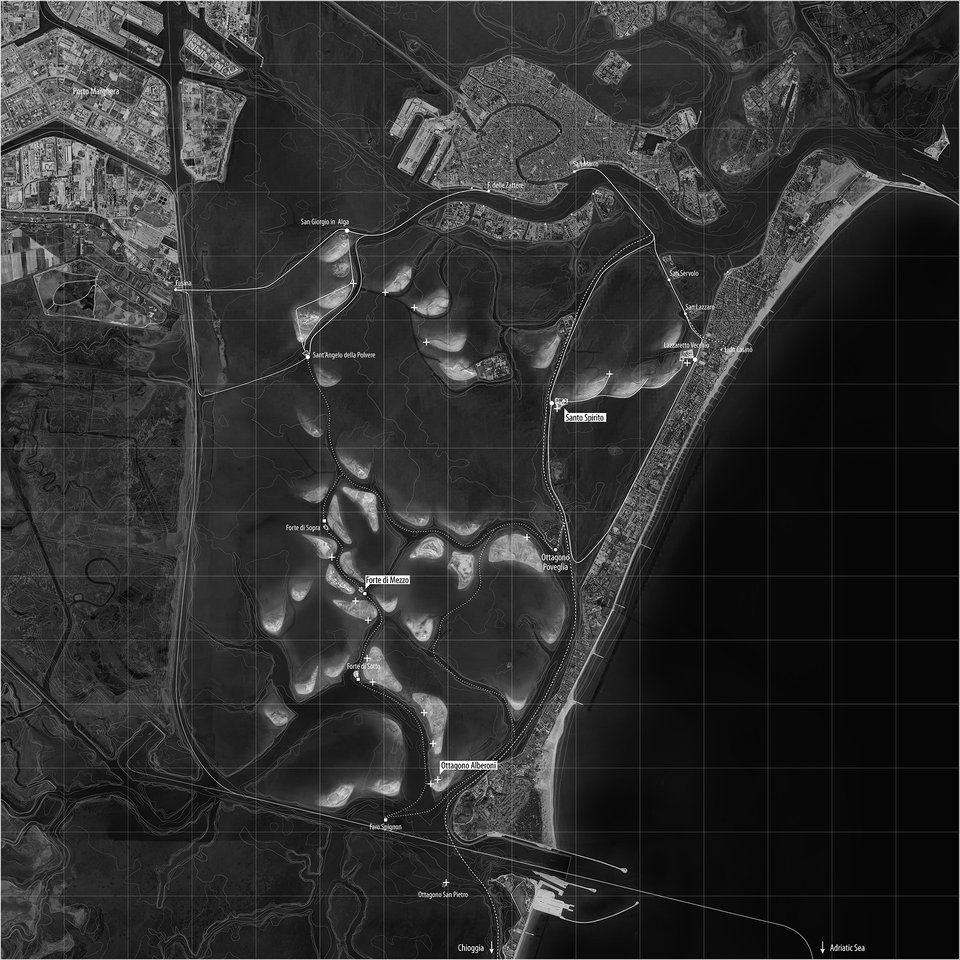

Like many other problems concerning water, the matter of medicine residue is not a new phenomenon. It is, however, becoming more urgent due to factors such as increasing urbanisation and a growing and ageing population. Climate adaptation is another increasingly urgent matter. “We need to be prepared for more extreme weather events, such as torrential rain or prolonged droughts. The government wants citizens to do more in their communities, but not everyone is in a position to do so. I’m looking into ways of putting this ambition of creating resilient neighbourhoods into practice, so that everyone will benefit and there won’t be a social divide between the areas that have got things nicely organised and the poorer areas that haven’t.”

It’s actually very similar to the energy transition problem. “A few years ago, you saw people who were better off reaping the benefits of subsidised solar panels, while ordinary people’s energy bills kept on rising steadily. The discussion about fairness regarding the energy transition is underway now, but there’s very little attention being paid to fairness when it comes to climate adaptation,” explains Doorn.

A clear division

The government’s style of communication also leaves a lot to be desired. “Even highly educated people have trouble understanding letters from the tax authorities, although the consequences can be very serious. In Canada, for example, the government is obliged to create websites that are accessible to those with low levels of literacy. We could do so much better here.” Something else that deserves attention is increased digitisation. “The government launches a new app or opens a digital help desk and thinks that citizens will understand.” Division can be closer than we think. “Thanks to active residents, my own neighbourhood has really brightened up, with a local park that also serves as a water storage facility. The government cites neighbourhoods like this as an example, but not all neighbourhoods have the same degree of social cohesion or the legal literacy to apply for subsidies. This is how gaping inequality comes about.”

In 2019, Doorn received a Vidi grant worth € 800,000 from the Netherlands Organisation for Scientific Research (NWO). She will use it to study the extent to which citizens’ responsibilities under climate adaptation policies can be distributed fairly and effectively. Finding a research method is a challenge in itself. “Traditionally, philosophers tend to think about what certain terms mean, but this can be somewhat abstract and far-removed from reality,” says Doorn. An alternative is to interview people or to conduct a survey, but that doesn’t give a complete picture either. “It isn’t enough just to ask people what they consider to be important. Who do you ask and what about future generations, who don’t have a say? In philosophical circles, a lot of thought has gone into how to make fair decisions and which values should be taken into account. If you depend on the people who happen to take part in a survey, you risk missing the broader perspective.”

“I try to combine people’s opinions of what is fair and honest with information from philosophical literature,” Doorn continues. “For example, if you ask someone without a philosophical background how you can share risks fairly, the answer will probably be that we should ensure that risk levels are the same for everyone. However, from the philosophical perspective, I would say that we should also consider the extent to which people are capable of doing what we ask of them. Our calculation models for flooding risks are based on the idea that an 85-year-old woman is at the same risk of having to be evacuated as a young, fit person. This isn’t realistic.”

Common thread

Doorn developed an interest in the ethical aspects of engineering at an early age. She started as a student of Civil Engineering in 1991 and describes herself as a “traditional Delft child, good at the sciences.” She was also an idealist. “At the time, they were having dreadful floods in Bangladesh, so I decided to design an Eastern Scheldt Barrier for Bangladesh. Luckily, some of my lecturers were quick to offer advice: ‘Perhaps you should first check that our local designs are suitable for the situation there.’ I didn’t lose my fascination for engineering and water, but I did develop an eye for the more ethical aspects, although that’s not how I would have referred to it at the time.” The combined social and intellectual drive has been the common thread throughout her career.

Highly relevant

After graduating, Doorn started work as a researcher at Deltares while simultaneously studying philosophy. “I needed to be able to reflect upon my work,” she explains. She then went in search of a PhD position on the interface of engineering and ethics, which she found at TU Delft: Doorn examined the distribution of responsibilities within research teams. Doorn laughs: “A colleague from Deltares said: ‘If that counts as ethics, it’s highly relevant.’” It’s a subject that she still considers to be extremely relevant in her work. “If a lot of people are working together, developing new technology for example, you have to ensure that all the responsibilities have been shouldered. You see that people working on the practical side assume that the risks have already been calculated earlier on in the chain, while the people earlier on in the process were actually focusing on the fundamental side of the research, thinking that risks are part of the application side. Everyone is waiting for the others to act.”

This is the kind of insight that Doorn and her colleagues try to impart to students across the University. Whereas this used to be taught in separate ethics modules, these days ethics is usually incorporated into other modules in the Bachelor curriculum. “We hope to teach Bachelor’s students that there’s more to engineering than doing calculations, that we are all continually weighing up values in the course of our work.”

During the Master’s phase, students can then follow thematic ethics courses, taught by Doorn or one of her colleagues. “I am currently teaching the elective module in water ethics. It’s great to see Master’s students from a whole range of disciplines, such as architecture, civil engineering, marine technology and systems engineering, policy analysis & management, all working together. They all feel that their perspective on a problem is broadened by looking at it from a different angle with fellow-students from other programmes.” The module also includes a joint case study. “Last year, a group came up with a serious game about groundwater extraction in Pakistan. Nestlé pumps water up to sell as bottled water, but the practice is bad for local farmers. The game is a great way of helping people to understand a complex issue.”

Study stress

Doorn sometimes worries about the students’ welfare. “They have so much to cope with: the system of student grants and loans has changed, they have to make countless choices, and an awful lot is expected of them. To compound this, they’re also trying to contend with being young adults. All in all, it can generate a lot of stress. I’m glad that Rob Mudde (Vice President of Education, ed.) is paying attention to this aspect,” she continues. “I try to tell my students that they’re already doing well if their programme is going smoothly. They will graduate from this university with a highly regarded degree certificate. While it’s good to do something else alongside your studies, it’s by no means obligatory to be in a dream team and take an honours programme, to excel in music and sport and to have an active social life. You can’t do it all. I’d like students to feel less pressure in this respect.”

This also applies to her colleagues. “We all work very hard and we share a ‘we can all do it together’ mentality. That’s great and I wouldn’t want it any other way, but there’s definitely a risk that we’ll all work ourselves into an early grave in the academic world. While it’s tempting to think that it’s down to the system, we would do well to realise that we are the system. So it’s up to us to bring about change, in doctoral programmes for example. Doctoral candidates have four years to develop into independent researchers, not simply become people who have published eight papers in high-ranking journals. Let’s shift the emphasis from quantity to quality. If we don’t make these choices, it will be detrimental to the quality and ultimately to ourselves.”

Privileged

Doorn has never regretted choosing Delft: “This is where everything comes together: my civil engineering and my philosophical background,” she says. “Obviously there are philosophers who make relevant contributions to the philosophy of engineering without a technical background, but I am extremely grateful for mine. I’ve also noticed that I’m closer to the practical side of water now that I’m a professor. I’m every inch the engineer, as well as a philosopher. This unique dual profile allows me to make serious progress. And even if I’m not the only person looking into ethics and water, Delft is the only university with a professorial chair in the subject. So I feel privileged to be here doing what I’m doing.”