Playing a board game in the evening with family or an online game with friends is fun, but games are also used in business and government settings to get a grip on complex situations. Such as promoting safety in the chemical sector or how to open restaurants safely with covid-19 measures. At the Faculty of Technology, Policy and Management (TPM), researcher Simon Tiemersma and his team make interactive models that can test fictitious situations, also known as serious games. A Gamelab facility has even been set up for this purpose.

Informality as a strength

‘Serious gaming has been around for a long time, but its use is still limited’, says Simon Tiemersma, team leader of the Gamelab. According to Tiemersma, this is because games have an informal character. ‘But that is precisely the strength of these games, because with the informal character comes the pleasure that people experience in a serious game. With pleasure comes engagement and empathy which makes people look at a problem differently, which then helps to get to the core of the solution’, according to Tiemersma. Incidentally, the Gamelab is not intended for the design of games for commercial purposes; using games for research purposes is paramount.

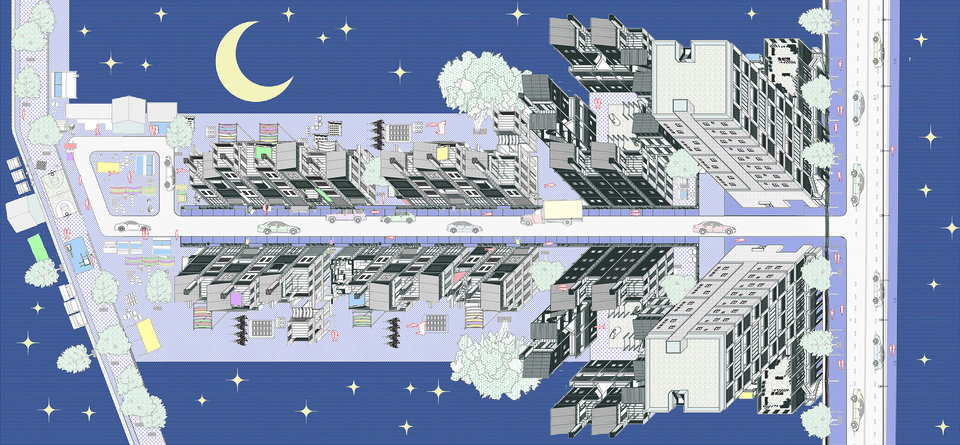

Tiemersma came into contact with the Gamelab about seven years ago because his graduation project was about Architecture and Gaming. Tiemersma: ‘Games offer many opportunities for serious use in many disciplines, due to their interactive nature. I wanted to investigate this with a design for interactive architecture.’ After his graduation, he was asked to come and work at the Gamelab. ‘It was an easy decision for me, since I could make a career out of my hobby.’ Since then he has worked on many games as a game designer, graphic designer and project leader.

Design of serious games

The design process of a serious game follows a creative step-by-step plan. ‘It is a creative process, but there is a certain sequence that you go through, together with experts’, says Tiemersma. As an example, he mentions a game to train employees on safety in chlorine plants. ‘First you delve into the subject, together with the experts. In this particular case, the clients of the game from the chlorine organisation EuroChlor also help in the design process. In a number of brainstorming sessions, you uncover the problem and determine what the game must achieve.’ How many brainstorm sessions are needed depends on the subject. These sessions lead to a first draft that describes the rules of the game and what it should look like. This is followed by the construction of a prototype. It depends on the desired end product of the client what is delivered, but in case of a complete game design, Tiemersma delivers a physical prototype that can be tested with the target group. With the feedback from the target group, the game is repeatedly improved until the desired result is achieved. The EuroChlor game is currently in the testing phase. Eventually this should lead to the final product, a facilitated board game.

Digital or analogue?

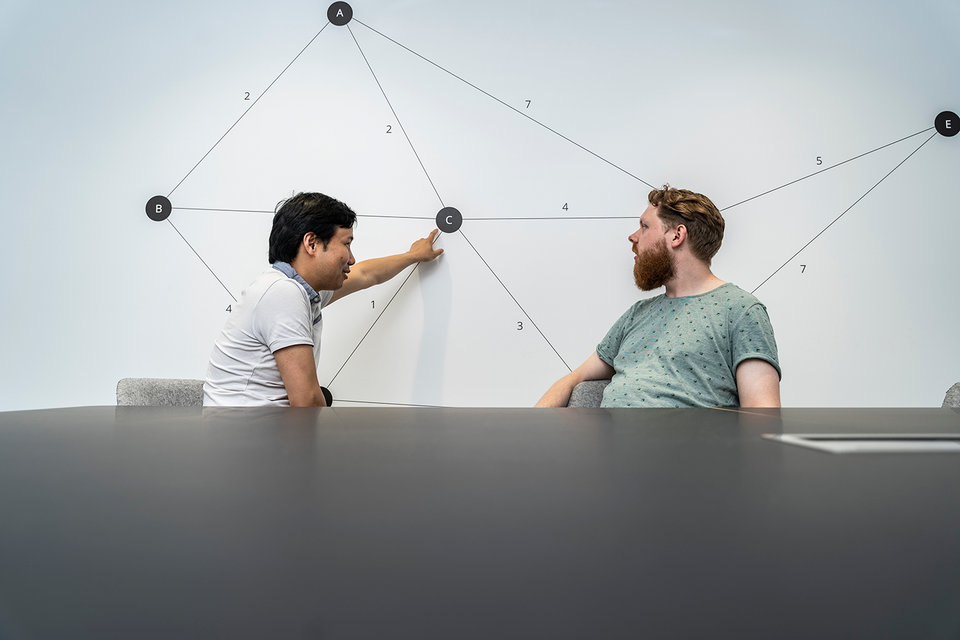

A serious game can be a digital or analogue game. ‘The advantage of a board game is that it is cheaper to make than a digital game, because it takes more time to develop a digital version. A board game is suitable for all ages, which is important if you work with older people who sometimes have difficulty with more advanced controls of games. A disadvantage is that board games have a smaller reach than digital games.’ For research purposes, board games mainly provide qualitative data, according to Tiemersma. This is in contrast to digital games, where quantitative data is collected. A major advantage of a digital game is that you can make very elaborate technical and visual simulations, which may help to achieve the objective of the game. Tiemersma himself finds physical games the most ideal. ‘Because then you can literally put people around the table and start a discussion.’

CPR game

Two serious games have particularly stuck out to Tiemersma so far. The first is Held (Hero): an app on your phone, aimed at teenagers to learn how to resuscitate. ‘With this game we could immediately see the effect of serious gaming. Besides the app, a physical CPR course was also offered to the teenagers. They were divided into two groups: one group followed the course completely physically and the other group played the app in combination with a short physical course.’ Tiemersma and colleagues investigated whether there were differences between the experiences of the two groups. And it turned out that the second group found it more fun to follow the course with the app and also played the Held app after the course. The CPR knowledge they gained was therefore better remembered.

This game was a bit of an odd one out, since the Gamelab usually designs games for research into complex systems. After all, the Gamelab is part of the faculty of TPM, where the emphasis is on control systems and modelling, and Held, as a training game for teenagers, does not fit in as well. ‘I do like the fact that Held is fully developed visually and graphically at a high level, while most of our games remain prototypes’, says Tiemersma. ‘We are also proud that this game was nominated for Best Serious Game at the Dutch Game Awards a few years ago.’

Learning experience

The second game that stayed with Tiemersma was made for the Municipality of The Hague. Unlike Held, the design of this game was less successful. Tiemersma: ‘It was one of the first games I was involved in. We needed a game for transport experts. My supervisor advised to keep the complexity of the issue in the game. The test session showed that this unfortunately made the game very confusing for the players.’ Tiemersma did learn a lot from this though: ‘A game is almost always better if it is not complex at its core. The complexity has to come from interactions with the systems of the game and from interaction between the players. Players bring their own knowledge and the game then serves as a means of solving situations in a playful manner.’

The future of the Gamelab

Tiemersma is keen to expand the Gamelab's research, rather than attracting new issues from industry, he would like to focus on independent research into serious gaming techniques. ‘What works and what doesn't? For example, do people learn better if the game is designed in such a way that players are bound to make mistakes? Insufficient research has been done into this yet. It would be a great challenge for the Gamelab, according to Tiemersma. ‘Then we can really make a difference in this field of research,’ he says enthusiastically. This would also tie in very well with the Delft association for serious gaming that is being developed: Delft Serious Games. The idea is that the Gamelab will then collaborate with companies that produce serious games. ‘This will benefit the visibility of serious gaming and may help deepening the research into serious gaming techniques.’