1. Assessment values and guidelines

Assessment values help to make consistent decisions on assessment. This chapter explains what the current TU Delft vision on assessment is, for each of the following four aspects:

- What the value of assessment is at the TU Delft?

- What the TU Delft assessment values and resulting quality requirements for assessment are?

- How the TU Delft defines and maintains assessment quality?

- How the combination of all TU Delft assessment tools support this?

The scope of the TU Delft vision on assessment is good quality assessment. The vision on assessment follows the vision on education3. Since the vision on education differs per faculty or even per programme, a directive central vision on assessment would diminish the freedom for the faculties’ (and programmes’) visions on education and assessment. That is why the TU Delft vision on assessment focusses on good quality assessment, and that faculties and programmes will have different visions on education and as a result, different visions on assessment.

1.1 The value of assessment

-

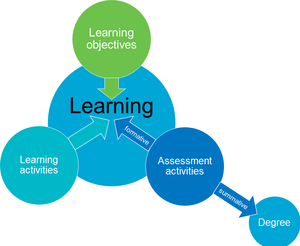

The TU Delft uses constructive alignment as a design principle for courses and programmes in order to support student learning.3 In constructively aligned courses, learning objectives, learning activities and assessment activities are aligned (see Figure 2). Learning objectives describe the ultimate but feasible level students are expected to achieve during a course. Assessments are educational activities (individual or in a group) during which individual students show how well they master the learning objectives (LOs) of a course. The TU Delft distinguishes between formative assessment and summative assessment(s). Formative assessments do not influence the course grade but give feedback on student learning (progress - and/or content related) to students during the course, while summative assessments determine the course result (grade or pass/fail). Courses consist of a combination of formative and summative assessment7, which supports the learning process of students. For lecturers, formative assessments help to adapt their teaching to the students’ needs during the course, while summative assessments provide information for course evaluation and improvements for the next course run.

-

3. Formative assessments result in feedback that is focussed on and structured per learning objective or assessment criterion. It holds valuable information on how well students do, and how they can improve. This enables students to steer their learning activities towards mastering these at the end of the course. In addition, lecturers use the information from the formative assessment to adapt the course to the needs of the students during the course run.

An activity counts as a formative assessment, if the following requirements are met:

- if the assessment is either at the level of the learning objectives, or (in case of e.g. assessment of draft products) or it if students can extrapolate the level of the assessment to the level of the learning objectives (otherwise it is a learning activity)

- if the performance of students during the activity does not count for the course gradeb or passing the course, and if the activity is voluntary (otherwise the assessment is summative)

- if students receive structured feedbackc on the applicable assessment criteria or learning objectives. The feedback gives useful information on whether they are on track to reach the learning objectives by the end of the course. Example: feedback via a rubric.

- if students are able and stimulated to use the feedback in consecutive learning activities and summative assessment (alignment with summative assessment)

Feedback can be provided by teaching staff, by peers, or by self-evaluation. The most important success factor for participation in formative assessment is timely and good quality feedback on these formative assessments8. This implies that training, tools, and time empower feedback providers. In addition, programmes have a policy on formative assessment (see 4.2) which ensures alignment between courses within an educational periodd.

-

Summative assessments determine the result of a course. The goal of summative assessment is to evaluate how well individual students master the learning objectives (assessment of learning), and whether this is sufficient to pass the course. Summative assessment(s) lead to a course grade, which reflects to what extent an individual student masters the learning objectives at the end of this course. Depending on whether the grade is sufficient, this will lead to a pass-fail decision for that course.

-

Course grades represent how well individual students master the learning objectives at the end of the course. Grade 10 indicates that the student masters the learning objectives fully. Grade 6 indicates that the student masters the learning objectives on average just sufficiently to pass the course and start the consecutive course, start a consecutive degree programme, or start a professional career. This depends on the place of the course in the programme (more information on ‘Scoring and grading’ in 3.5).

-

An programme assessment plan is the overview of all (summative) assessments of all courses in a BSc or MSc programme. Its goal is to demonstrate that the programme’s various assessments secure qualified graduates. Therefore, the programme’s assessment plan shows how the learning objectives of the courses cover the final attainment levels (FALs) of the degree programme. FALs describe clearly what graduates of the specific programme should be able to do. FALs are also called intended learning outcomes (ILOs) during accreditationse.

Subsequently, the assessment plans of individual courses show how their learning objectives are covered by the assessment(s) and their appropriate method(s), ideally including formative assessment. This combination of programme assessment plan and course assessment plans ensures that graduates master the FALs, which secures that they are justifiably awarded with the bachelor’s or master’s degree of the TU Delft.

1.2 Assessment values and quality requirements

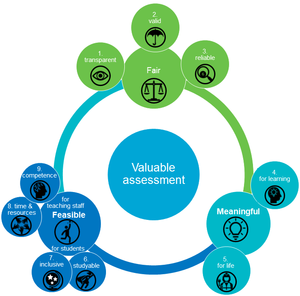

The assessments at TU Delft should be fair, meaningful, and feasible. The TU Delft strives towards these three assessment values and they form the basis of decisions on assessments. They are the basis for the following 9 quality requirements for assessment (see Figure 3) that match the TU Delft vision on education3, the TU Delft vision on teaching and learning9, and the assessment framework for the higher education accreditation system of the Netherlands10. Since it is impossible to obtain all requirements simultaneously, the TU Delft strives for a balance between the nine assessment requirements.

The value ‘fair’ consists of 1) transparency, 2) validity, and 3) reliability. The value ‘meaningful’ consists of meaningfulness 4) for learning and 5) for life. The value ‘feasible’ consists for students of 6) studyability and 7) inclusivity, and for teaching staff of 8) time and resources and 9) competence.

-

Quality requirement 1: transparent

The course examiner is transparent about the assessment and grading before, during and after the assessment, because this is essential information that empowers students to achieve optimal learning. In addition, course examiners are transparent about feedback and complaint procedures. Quality requirement 2: valid

The assessment method, and the aspects and levels on which the students are evaluated (assessment criteria) are constructively aligned with the learning objectives, i.e. assess to what extent students master the learning objectives. Students are trained on these learning objectives during the course in learning activities. Quality requirement 3: reliable

The assessment is reliable if the grades and/or feedback are precise and consistent (discriminates correctly between good performing and worse performing students, and has sufficient precision), reproducible, and objective (e.g. unbiasedf), and represents the ability of individual students. This implies the assessment of (the contribution of) individual students in group work, partial grading, as well as fraud preventiong and fraud detection. See also ‘Meaning of grades (model R&G art. 14.4) in 3.5. -

Assessment is meaningful if it supports learning during the course and if the assessment method and content is relevant for and a reflection of their future professional or study situations. Quality requirement 4: meaningful for learning

Meaningful in the sense that individual assessments and course assessment plans supports learning and steer the learning process. This requires constructive alignment, timely feedback on the learning outcomes that students can apply in summative assessments, and a safe learning environment. This enables students to take ownership of their learning3. Quality requirement 5: meaningful for life

Meaningful in the sense that assessment methods, and/or cases/topics are relevant and authentic, i.e. represent real or realistic cases from the graduates’ professional careersh, have explicit relevance for future courses, and reflect the diversity of the (global) work field, its employees and society at large. -

Assessment is feasible if students and teaching team can complete inclusive assessments with the time, means and competence available. Feasibility for students implies

Quality requirement 6: studyable

Qualified students are able to pass courses if they effectively invest 28 hours per EC12, and qualified students are able to finish assessments within the allotted time. Quality requirement 7: inclusive

Assessments are accessible for students with the most common support needsi and take into consideration the diversity of the student population in terms of educational background, economic situation, as well as visible and non-visible differences. Feasibility for staff implies

Quality requirement 8: time and resources

Course examiners, together with the teaching staff, can carry out the course assessment plan within the available time, and resources like tooling, support, money and efficient assessment processes. Quality requirement 9: competence

Employees with a role in the assessment process are competent for their tasks. Information, advice, and training support their competence. How these values and their corresponding quality requirements are implemented, will be identified and noted throughout this document.

1.3 Assessment quality

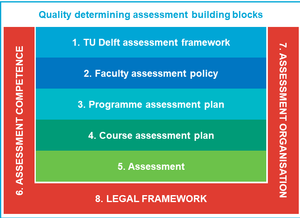

The TU Delft achieves good quality assessment because all aspects of assessments (building blocks) are consistent with each other and because both their consistency as well as their individual quality is monitored and improved in the Plan Do Check Act (PDCA) cycle13 of the Quality Assurance System of the TU Delft. This section discusses what these building blocks are and how this improvement takes place.

See running text. The red, surrounding blocks (6, 7, and 8) support and are the fundament of the central blocks (1-5).

Assessment at the TU Delft can be divided into eight aspects that we will call building blocks of assessmentj (adapted from the assessment web4, see Figure 4):

- TU Delft Assessment framework

- Faculty assessment policy

- Programme assessment plan

- Course assessment plan

- Assessment

- Assessment competence (of everybody with an assessment task)

- Assessment organisation (all levels)

- Legal framework (all levels)

These building blocks range from national level to assessment level. The TU Delft vision on education and the national legal framework are the basis for the TU Delft assessment framework, which includes the assessment vision. This framework, and the faculties’ educational vision and policy form the basis of the faculties’ assessment policies. The latter forms the basis for the assessment programs of BSc and MSc programmes, which are influenced by the programmes’ intended learning outcomes. From the programme assessment plans, the course assessment plans sprout, based on their learning objectives, with the actual tests at the bottom of this chain. The assessment organisation and assessment competence support all previously mentioned building blocks.

A faculty’s assessment policy can deviate from the assessment framework, if this is motivated by the faculty’s vision on education and if this does not negatively influence assessment quality.

At least every six years, the assessment quality of each of these building blocks is systematically assessed and improved by checking its requirements. Assessment is of good quality if each building block supports the assessment values (fair, meaningful and feasible), adheres to the previously described nine quality requirements for assessment, and meets the block’s conditions as described in the following chapters. The conditions are summarized per building block in the ‘Introduction and summary’ and summarised chronologically in Appendix A.1.

-

The TU Delft has a central quality assurance plan14 in place that describes a framework for how the quality of education (including assessments) has to be monitored and improved. Both in the faculty’s quality assurance handbook and in the faculty’s assessment policy it is made clear how the quality of the building blocks ‘programme assessment plan’, and ‘course assessment plan’ & ‘assessments’ is provided and monitored within the faculty’s organisation. So, the central quality assurance plan, the assessment framework of the TU Delft, the faculty’s quality assurance handbook, and the assessment policy of the faculty are aligned with each other (see Figure 5).

-

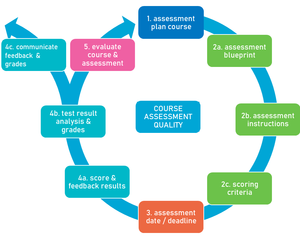

To continuously improve the quality of course assessment, examiners follow an assessment cycle. Most faculties will have assessment cycles that look like the following (see Figure 6):

1) develop/redevelop the assessment plan of the course; 2) develop the formative and summative assessment(s) (exam, project, assignment, etc.) of the course; 3) administer the assessments to the students; 4) feedback, score, analyse, grade, and communicate feedback and grades to the students; 5) evaluate the course and its assessment. See running text. Based on Expert group BKE/SKE (2013)15.

The steps comprise the following (for more details, see the TU Delft assessment manual16)

- Assessment plan course: develop or improve an assessment plan for the course, which includes the learning objectives, how formative and summative assessments will be combined, and how the final grade will be calculated.

- Develop the formative and summative assessment(s):

- Assessment blueprint:

- Assessment and assessment instructions (formative and summative):

- Exams/exam-like tests: develop questions and subquestions, and provide students with general instructions on answering questions and the available resources & tools during the exam beforehand, and on the exam cover page.

- Other assessment methods: formulate the assignment and include the assignment’s relevance (related to Quality requirement 5), learning outcomes, instructions, available resources, deliverables & due dates, assessment criteria, grade calculation and feedback possibilities17.

- Scoring criteria:

- Exam: develop an answer model. An answer model consists of at least the model answer and a scoring guidem.

- Other assessment methods: develop assessment criteria to assess the students’ work (rubric and/or assessment form), aligned with the LOs of the course.

- Assessment date/deadline: administer the assessment to the students. For exams, this happens during the designated time slot (called ‘exam time slot’) according to the procedures outlined in the TU Delft Rules of Procedures for Examinations (RPE)18, and in the applicable Teaching and Examination Regulations (TER) and Rules and Guidelines of the Board of Examiners (R&G)n. For other assessment forms, students can work on their assessment until the deadline.

- Grading process:

- Score and feedback: assessors (people who assess) score the students’ work and (if applicable) create structured feedback1o to the students.

- Test result analysis and grades: examiners use test result analysis as input for adaptation of the answer model/rubric and of the initial score-grade transformation, if necessary. Examiners calculate the grades using the score-grade transformation.

- Communicate grades and feedback: examiners communicate the feedback and grades to the students in time and according to regulations, and give students the opportunity to review their assessed work.

- Evaluate course & assessment: the test result analysis is used to analyse the learning objective achievement and is used together with the teaching staff’s and students’ experience, and the course evaluation (EvaSys) to improve next year’s course.

1.4 Digital assessment tools: goal and landscape

-

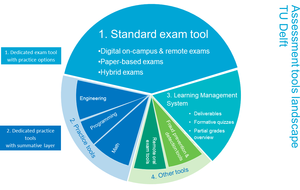

To reduce the assessment workload for teaching staff and to increase the assessment quality, the TU Delft has created a digital assessment tooling ‘landscape’ (see Figure 7) with a range of assessment related tools. The tools support the execution of the TU Delft assessment framework. Therefore, the goals of these tools are:

- Supporting and monitoring assessment qualityp.

- Supporting teaching staff in executing the assessment cycle (see Figure 6).

- Reducing the workload of teaching staff.

- Supporting both formative and summative assessment, as well as learning activities.

- Supporting the large variety in programmes and assessments (resulting in a landscape that consists of more than one tool).

- Supporting students in taking their exam (including accessibility for students with a support need)

-

The assessment landscape (Figure 7) of the TU Delft consists of the following elements in 2023:

- A standard digital exam tool (currently Ans) facilitates automatic and manual online scoring of paper-based, digital or hybrid exams (upper part Figure 7). It can also be used for formative assessment.

- Dedicated practice tools focus on learning a specific discipline and have a summative layer. There are tools for math (currently Grasple), engineering (currently Ans and Möbiusq), and programming (currently Jupiler Notebook, lower left part of Figure 7).

- Learning Management System (LMS) where students deliver reports, presentations, etc. and where teaching staff provides these with grades and feedback, checks for plagiarism, and keeps track of partial grades. The formative quiz-tool automatically provides feedback to multiple choice, numerical and brief textual answers. Current LMS: Brightspace.

- Fraud prevention & detection tools for on-campus examsr (lower right part of Figure 7), and online proctoring software (currently RPNow) to facilitate certain remote examss, and plagiarism software (currently Ouriginal).

- Oral exam tools: currently generic conferencing tools (dark green part in Figure 7)

b Students will of course learn from formative assessment. Learning will positively influence their course result (grade or pass/fail).

c Feedback that is structured per applicable LO or assessment criterion. The term is used as the opposite of ‘unstructured feedback’, in which not all LOs or criteria are systematically assessed.

d This is important if there are two parallel courses. If one of them has fully voluntary formative assessments while the other course has small assessments that counts for the course grade, students tend to focus on the second course.

e or exit qualifications

f In assessment literature, assessor bias is considered to mainly influence reliability (instead of validity), probably because most assessment effects are caused by the order in which the student work is assessed (sequence effect, norm shift, contamination effect, etc.11) and are therefore in general randomly distributed over the students.

g In exam settings, fraud is related to the conditions in which the exam was administered, and not related to the validity of the assessment itself. Therefore, it is listed under reliability. In assessments without invigilation (e.g. take-home assignments and projects), fraud like plagiarism and free-riding are explicitly forbidden, like it is in professional situations. Therefore, fraud is not assumed to influence the validity of the assessment, but the reliability. I.e., we assume that the reproducibility of the assessment is jeopardized.

However, in case of widely available tools (like AI tools) that graduates will use in their professional life, lecturers must assume that students will use this tool during non-invigilated assessments and adjust the learning objectives and assessment criteria accordingly. If the AI tool is not taken into account, the validity of the assessment is jeopardized.

h If this is appropriate and feasible for the course.

i See model TER2 art. 25.1: “Students with the [sic] support need means students who are held back due to a functional limitation, disability, chronic illness, psychological problems, pregnancy, young parenthood, gender transition, or special family circumstances, for example in relation to informal care”. Accessibility can be increased by for example using dyslexia-friendly fonts, colourblind-friendly colours, and clear instructions, and by offering TU wide facilities like the extension of exam time.

j ‘Building blocks of assessment’ are called ‘entities’4, ‘pyramid layers’5, and ‘building blocks’6 in literature. Since we are a technical university, ‘building blocks’ seems fitting.

k In an assessment matrix on exam level, learning objectives (LOs) are rows, and levels of the taxonomy (e.g. Bloom’s) are columns. Cells contain subquestion numbers and corresponding numbers of points/weights. Per learning objective (row), the cell(s) that correspond to its level of the taxonomy is/are highlighted.

l In a consistency check table, learning objectives (LOs) are rows, and deliverables/processes are columns. Cells contain the applicable assessment criteria and their weight (or points). Columns with formative assessments contain criteria with 0% weight.

m A scoring guide contains the number of (+) points per correct step, and (if applicable) a list of mistake/omission and corresponding subtraction points (-). For essay questions, a rubric can be used.

n R&G: Every faculty has their own abbreviation. See E.5

o ‘Structured feedback’ is feedback that is structured along the learning objectives or assessment criteria.

p Examples: the availability of user-friendly test result analysis will facilitate and stimulate lecturers to use them to adjust the answer model and increase the reliability of the grade; increasing the ease of giving feedback will stimulate lecturers to give good quality feedback; facilitating partial grading of open-ended questions will increase grade reliability compared to single answer numerical questions.

q Möbius is replaced by Ans as standard exam tool as of 2023.

r Currently, on-campus exams use a TU Delft based safe exam environment.

s Online proctoring exams can only be administered as a last resort, and after approval of the Board of Examiners19.

Need support?

Get in touch with us! We are happy to help.

- Teaching-Support@tudelft.nl

- +31 (0)15 27 84 333