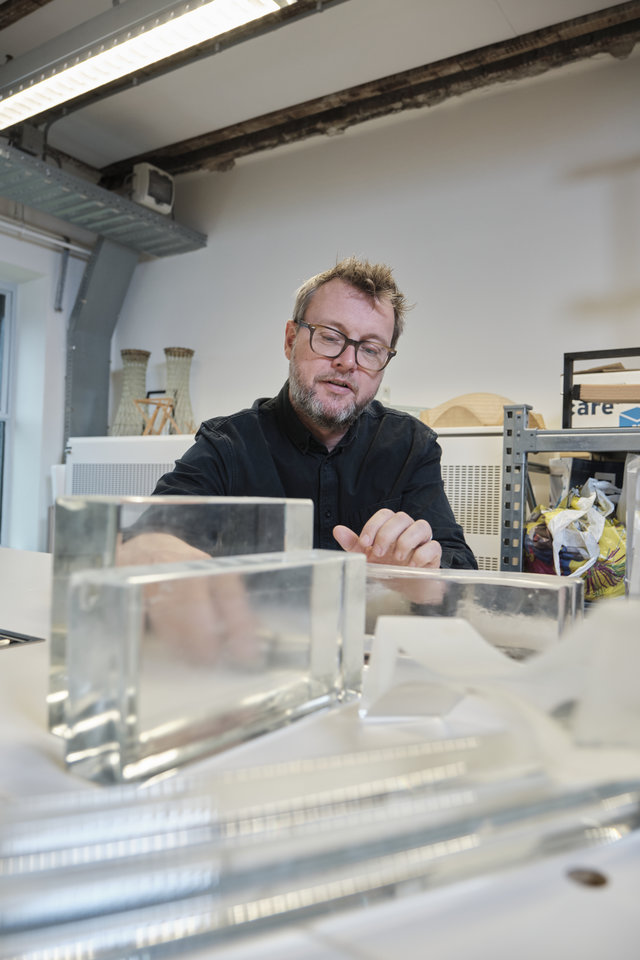

Urban dwellers need green public spaces. To put oxygen in their lungs and improve their mental health. To capture carbon dioxide and mitigate extreme weather. To ensure balance between the built and the natural environments. But in densely built-up cities there is little space for greenery at ground level. So, what can be done about this? For his graduation project, Menno de Roode studied and designed compact urban public green spaces: “Following nature as far as possible enables you to avoid unnecessary maintenance and management.”

In 2015 Menno started studying landscape architecture at Wageningen University & Research. His interest in integrating natural processes in urbanism led him to Singapore via an exchange programme. “There they have already made great advances in developing and managing nature in the city. One day I'd be wandering through the rainforest, and the next day I'd see the same plants being used in planted façades. You can't help but be inspired by that.” After his Bachelor's programme, he continued his studies at Delft, where he specialised in ecologically responsible urban design. There's nothing new in paying attention to public green spaces in urban planning, says Menno. In post-war neighbourhoods a lot of space was given to public parks and gardens. “But these designs were not based on working towards a naturally functioning city. The green areas had mainly a social, recreational and aesthetic function; the monotonous greenswards, flowerbeds and hedges did little for biodiversity. Nor did they link up to the natural environment in or beyond the city.” How times have changed. Collapsing ecosystems coupled with climate change demand other forms of urban development. “The emerging trend is: how can we do things as naturally as possible?”

From mountain top to riverbank

Space for greenery was traditionally sought at ground level. But in our densely built-up cities, this space is limited. Roofs and façades offer more perspective, and in recent times green walls and roof gardens have been gaining ground. However, Menno feels there is still room for improvement. “For example, you see more and more sedum roofs, but an individual surface covered with one or two species of succulent does not make much of a contribution to biodiversity.” He collected and conceived typologies for green structures that function ecologically and also promote the liveability of the surrounding area. “Seeing the city as a cohesive entity of biotopes, from mountain top to riverbank, enables you to make logical links between different spaces and the species that thrive there.” For example, on a tall building you wouldn't want to use tender plants that need a lot of water. Such plants need to be able to exist in harsh conditions. “Following nature as far as possible enables you to avoid unnecessary maintenance and management.” From a landscape perspective, paved streets and high-rise buildings form a mountainous and somewhat arid environment, explains Menno. “There's a good reason why urban planners talk about the ‘urban canyon'. Yet some species of bats and swallows, and birds like peregrine falcons, feel right at home in such a 'stony’ environment. You can help such species by building holes and nesting areas in buildings.”

Green patterns compiled in atlas

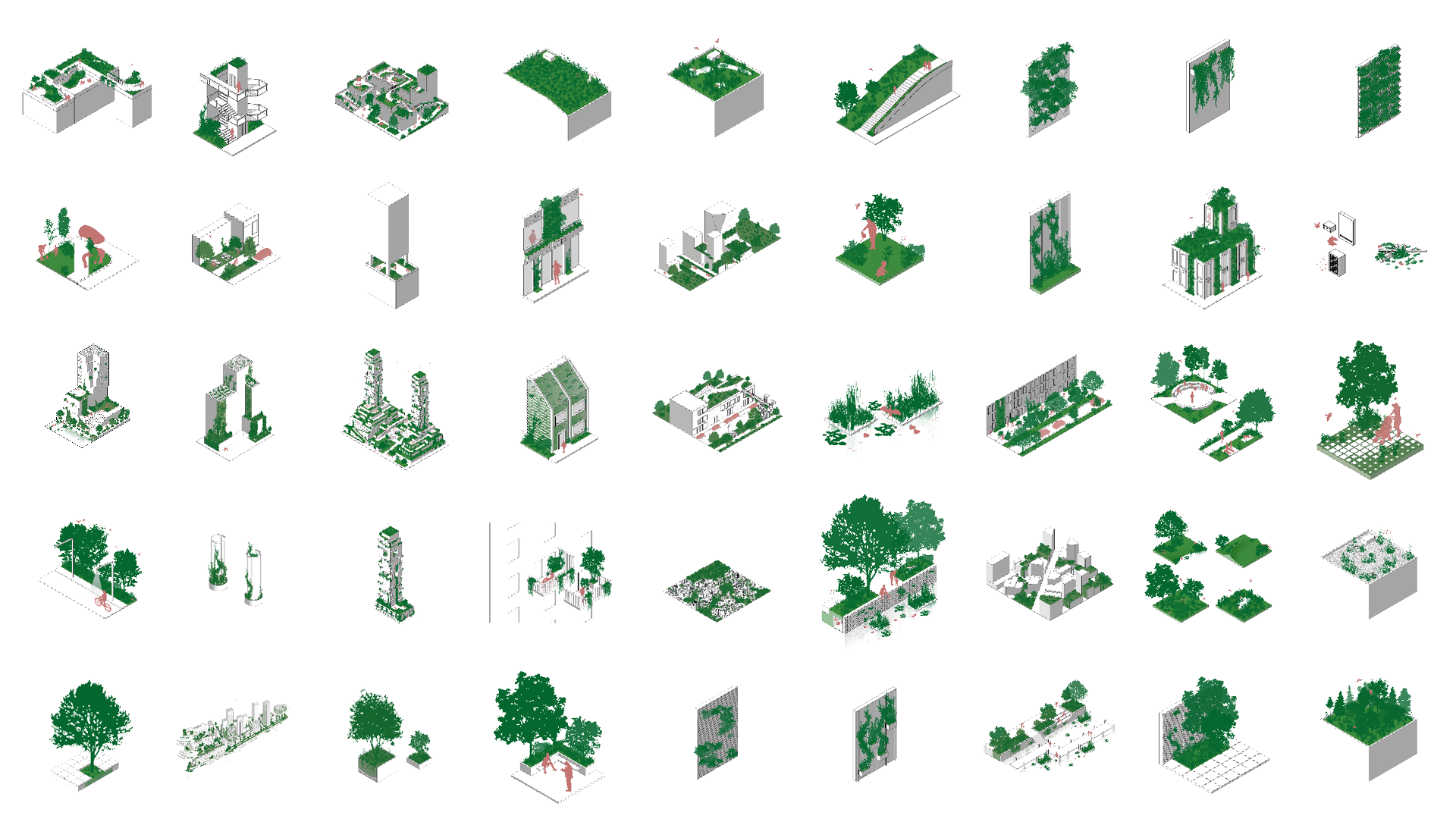

From sky park to pocket park and from eco-façade to wildlife corridor: Menno encountered 34 green patterns or structures that he described and compiled in a well-ordered atlas as a supplement to his thesis.

For every structure an indication is given as to how well it scores on ‘ecology’ and ‘wellbeing’. “The idea is that on different levels and scales, from small to large, you can create structures that link together and form an ecosystem that fits the individual city. Examples include a rooftop landscape comprising multiple roofs that is linked to ground level and the soil by stairs or façades. This enables various plant species to develop and spread. These attract all kinds of insects, and other animals benefit from this. Moreover, making a rooftop landscape of this type accessible enables people to enjoy a pleasant green outdoor space.” But what about hay fever caused by pollen, or skin rashes from oak processionary moth caterpillars, and other unpleasant consequences of more nature in the city? Menno grins: “Yes, those exist too and I mention them in my thesis. This is why it is important that a design promotes ecosystems but limits nuisance to a minimum. And this requires knowledge about nature.”

Radical greening

Menno applied his typologies to Rotterdam and identified a number of promising sites. “When you know that green roofs that are a little lower, up to 15 metres above ground level, are best for biodiversity, and particularly when they are situated near to other green areas, you can conclude, for example, that greening a cluster of flat roofs near Ahoy in the vicinity of the Zuiderpark, would be absolutely certain to raise the natural value of the living environment.” He is already drawing up a case study for the Wijnhaven area. “The city is keen to increase the building density here. I have drawn up a proposal for radical greening that also allows for additional living space.”

Menno is a real busy bee. He also took the opportunity to start an experiment together with a biology student from Leiden University – a fellow participant in the Urban Ecology Lab. How much biodiversity can you achieve with a roof garden? “A tree nursery in Cuijk made space available for us on their roof. We are experimenting with seed mixes in three types of soil. What plants grow well in what soil? What insects do they attract?” The experiment is still ongoing, but Menno can already share the fact that the local soil has the highest vegetation cover. “The nurseryman was a little concerned that the ‘weeds’ would spread to other parts of his roof garden. While to my way of thinking, the plants that settle and grow independently probably form the most suitable vegetation for an ecologically strong city. After all, they have adapted optimally to a certain microclimate.” So more ‘wilderness’ leads to more resilience? “I think so. But we haven't thought that far ahead yet. Besides a new kind of spatial planning, the ecocity demands a new way of thinking.”

Green walls on campus

At home Menno's view consists of brick walls. “I had already been thinking for a while about brightening up the view by creating a green wall indoors. The pandemic gave me just the push I needed.” He mounted irrigation mats on panels to create a vertical structure in which plants can take root and are watered using a pump and a reservoir. The prototype worked so well that Menno’s thesis supervisor and driver of the Urban Ecology Lab, Nico Tillie, asked him to help supervise first-year Master's students in a landscape architecture elective, so they could make three walls for the faculty and one for the Botanic Garden, planted with lettuce and parsley. “That was really great, especially now I want to start up developing and selling the product further under the name Compact Green. The idea is to install a similar wall in the restaurant at Architecture and the Built Environment, so that everyone can pick their own mint for in the tea.”

More information

The international EcoCity World Summit is taking place from 22 to 24 February 2022. TU Delft's Architecture and the Built Environment have helped to organise this gathering, which will be chaired by Dr Nico Tillie and Prof. Andy van den Dobbelsteen

During this Ecocity World Summit Menno will talk about his research and findings.

His Master's thesis and the atlas can be downloaded here.

You can also read the previously published account of Urban Ecology and the research conducted by Nico Tillie.