As climate change and conflicts are displacing more and more people across the globe, the demand for shelter and temporary housing is growing. In her master’s thesis Julia Gospodinova zooms in on transitional housing practice and offers designers and decision-makers a method to make practice more circular. “Matching acceptable living conditions with environmental, social and economic sustainability is essential.”

Born and raised in Bulgaria, Julia studied architecture in Stuttgart, also attending courses at Sapienza Università di Roma. As an undergraduate, her interest in sustainability issues brings her to join the Sustainability Committee of the AEGEE / European Students' Forum. “After working in Dresden for two years I came to Delft to acquire more technical knowledge and get a better grasp of circularity principles.”

Upfront planning

In Delft she joined the Project Safe Refuge, an initiative by young designers to research and develop transitional housing units for Ukrainian refugees. Transitional housing, she explains, is meant to provide shelter for people for longer periods of time, from six months to maybe three years. “Finding out how circular principles might be integrated into such semi-temporary housing seemed a good topic for a thesis.”

Studying the practical aspects of humanitarian aid she finds out that relief organisations approach shelter and settlement projects quite differently, ranging from grassroots movements to top-down management. Also, for various reasons, information on what actually happens to goods and materials after usage is sparse. “An online course by the International Federation of Red Cross and Red Crescent Societies (IFRC) helped me to better understand how shelter is provided in crisis situations. I also learned a lot from people, working with Eefje Hendriks, who is assistant professor of Disaster Resilience and Humanitarian Assistance at University of Twente.”

Shelter components, often made of materials such as plastics and aluminium, are still frequently thrown away or incinerated after they’ve served their purpose, leading to pollution and a substantial loss of material value. “Innovation in the humanitarian sector is lagging. Incorporating circularity in transitional housing can foster innovation.” Since some countries and regions are particularly prone to flooding, heatwaves and other climate-related risks, more sustainable responses could be planned upfront, she suggests.

Incorporating circularity in transitional housing can foster innovation.

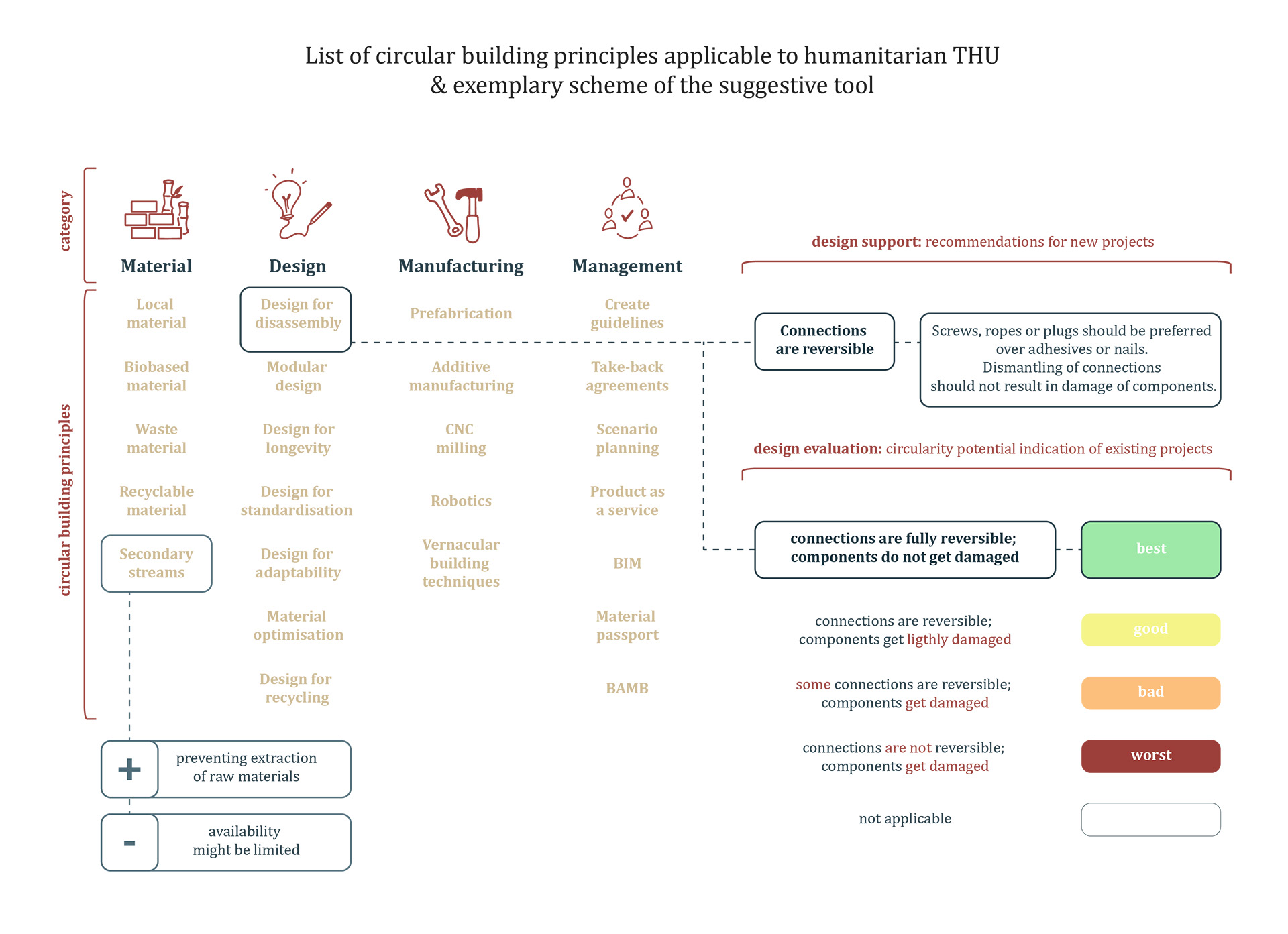

Material banks

Focussing on transitional housing units, Julia maps out both benefits and risks of applying circular building principles in four domains: design, materialisation, manufacturing and management. “The use of locally available materials, for example, can reduce costs and transportation time but may lead to the depletion of reserves.” In all, she identifies 24 circular building principles on the basis of which she develops a tool for designers, planners and other stakeholders with a dual functionality: a list of recommendations to be used during the design process and a visual evaluation for existing projects. “Various considerations in all four categories, as visualised with traffic light colours from green to red, offer the user an overall assessment of the circularity potential of a design in a particular setting.”

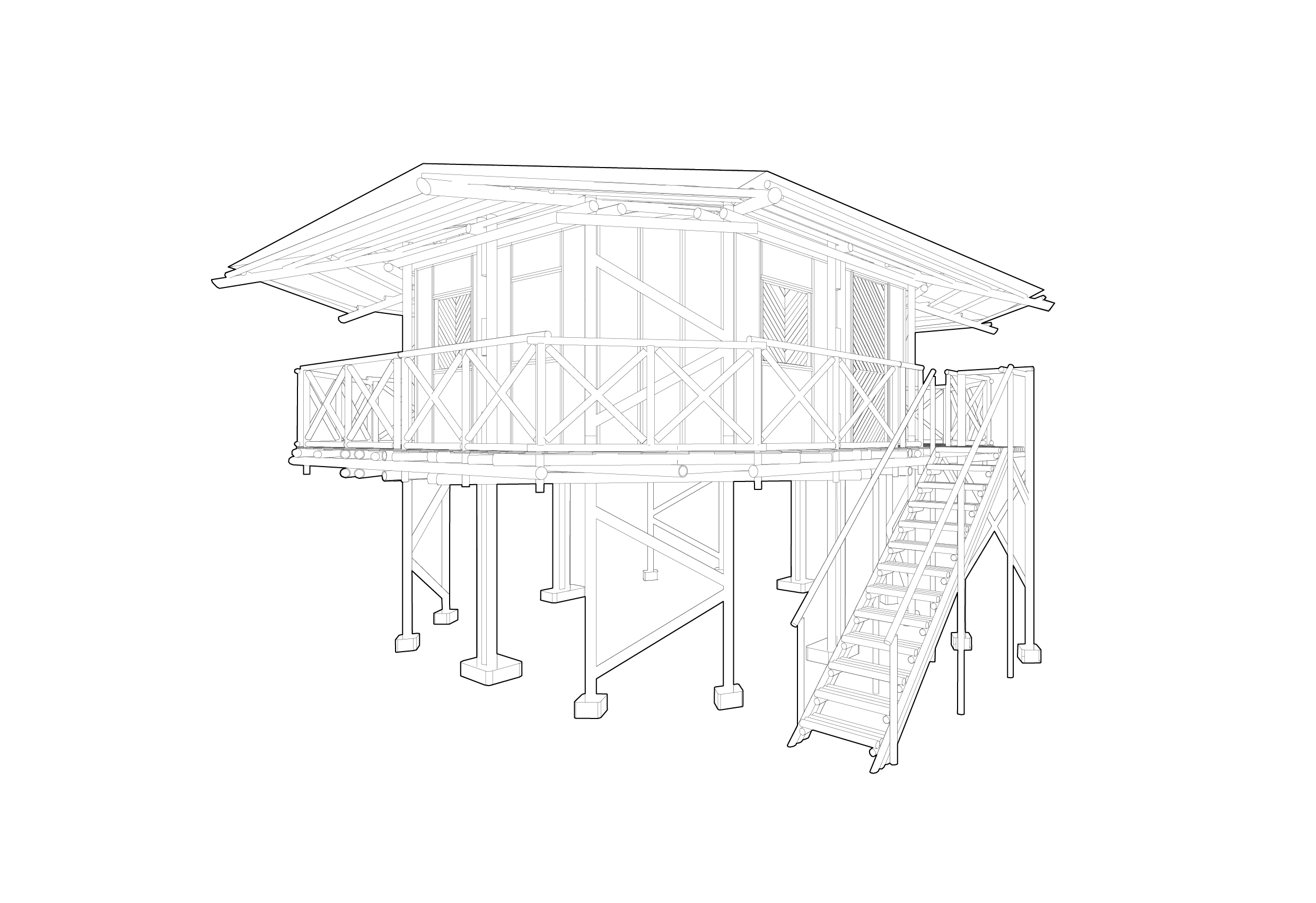

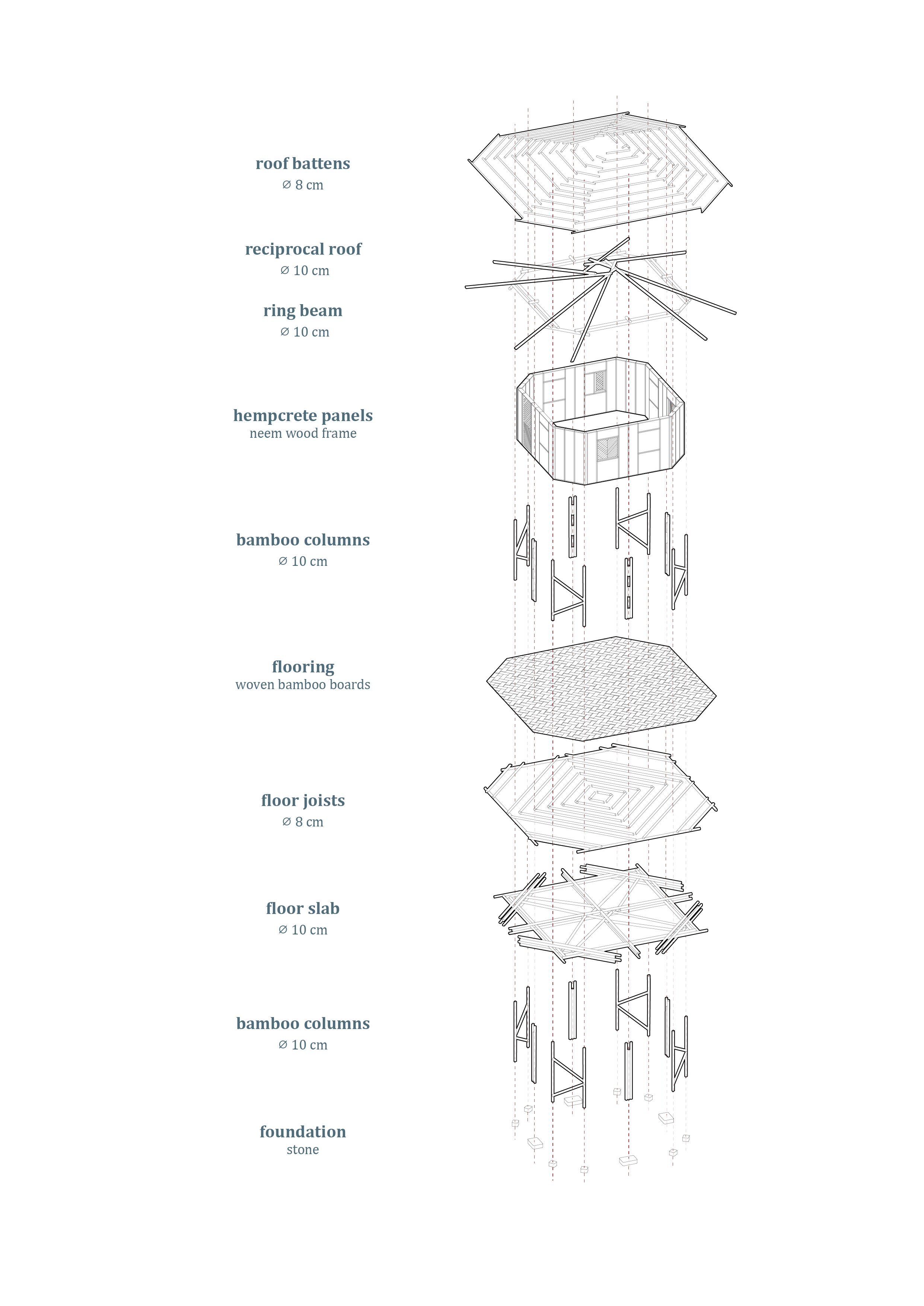

To show how it might work, she applies her tool to the Pakistani province of Sindh, where as recently as 2022 severe flooding displaced entire communities. “I identify bamboo, lime and hemp as bio-based building materials with a lot of potential, being widely available in the region.” From lime and hemp shives, hempcrete panels can be manufactured, which possess excellent thermal qualities. “By enabling component disassembly, housing units built with such panels could serve as material banks to the local economy.” At the same time bamboo is looked down on as a poor man’s material, she says. And although it can be legally grown to produce fibres, hemp is a type of cannabis easily associated with drug use. “Social and cultural prejudices are among the factors that determine whether circular building principles may be applied anywhere on any scale.”

It’s complicated? “Yes, there’s a considerable gap between theory and implementation. However, I do see a growing interest for the subject in the humanitarian sector. Guidelines for sustainability have been developed. I know of a project seeking to replace the plastic tarp of shelters by a material with a smaller CO₂-footprint. Change is slow, but it’s coming.”

This story is published: March 2024

More information

The complete thesis is available through this link:

Julia Gospodinova graduated under the supervision of Olga Ioannou and Job Schroën.

Circularity in the Built Environment Graduation Awards

Julia Gospodinova is one of the five winners of the Circularity in the Built Environment Graduation Awards 2022-2023. With her graduation project she was elected one of the two winners in the category 'Buildings & Neighbourhoods'.

The Circularity in the Built Environment Graduation Awards recognise the contribution BK graduation students make to the transition toward a circular built environment. These annual awards aim to stimulate research and innovation in the field of circularity in the built environment.

The Circularity in the Built Environment Graduation Awards is an initiative of the Circular Built Environment Hub of the Faculty of Architecture and the Built Environment, TU Delft.

Read also the stories of the other four winners.

Julia Gospodinova

Winner Circularity in the Built Environment Graduation Awards 2022-2023 in the category 'Buildings & Neighbourhoods'.