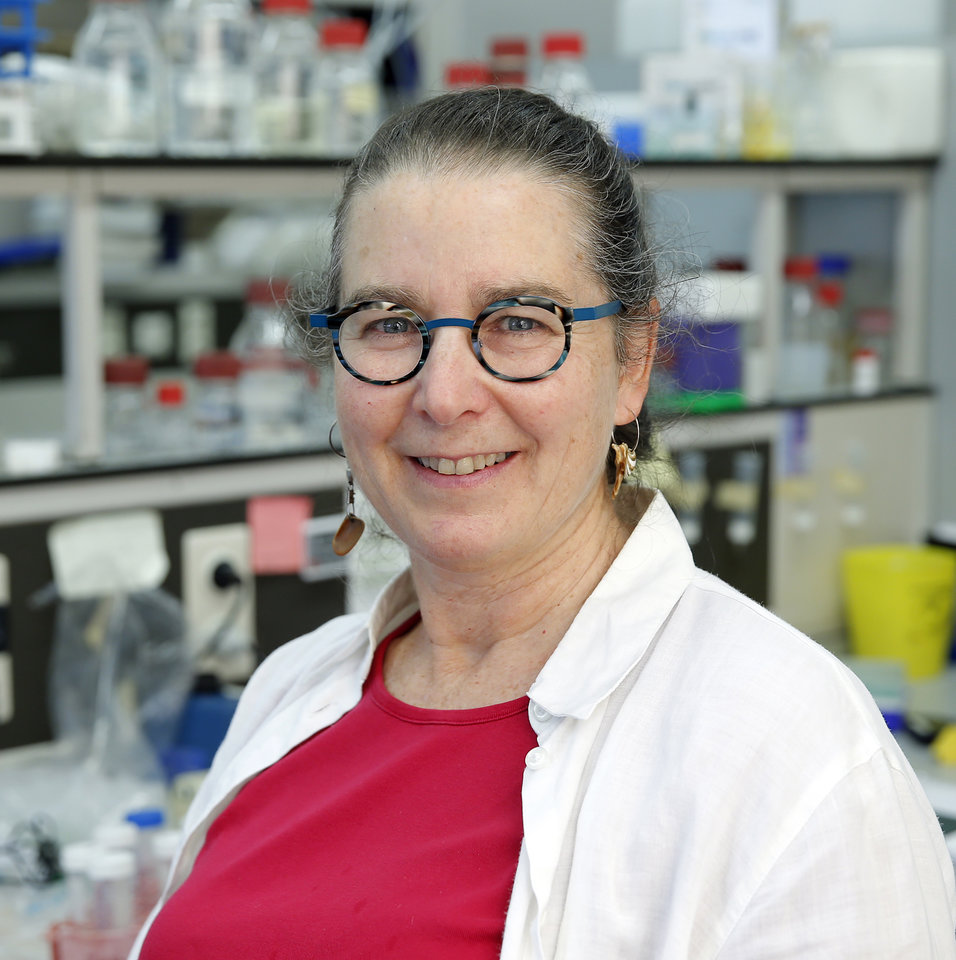

How do you design houses to encourage healthy behaviour? Where in a neighbourhood do residents meet? And what makes a housing block inclusive? Questions like these have occupied Dr Birgit Jürgenhake for years. She started her career as an architect, and now she is also educating a new generation of conscious architects and designers with her master's course 'Towards an inclusive living environment'.

To organise this master's course, Birgit collaborates with Habion, a large housing association specialising in homes for the elderly. "Habion needs out-of-the-box ideas, and my students can provide them." During the course, Birgit sends groups of her students into the selected neighbourhood for three weeks to interact with as many residents as possible, especially the elderly. After that, they create a development plan for a part of the neighbourhood. Two master students talk about their experiences and findings.

Tijmen Kuyper: reinventing the ‘spirit of the neighbourhood’

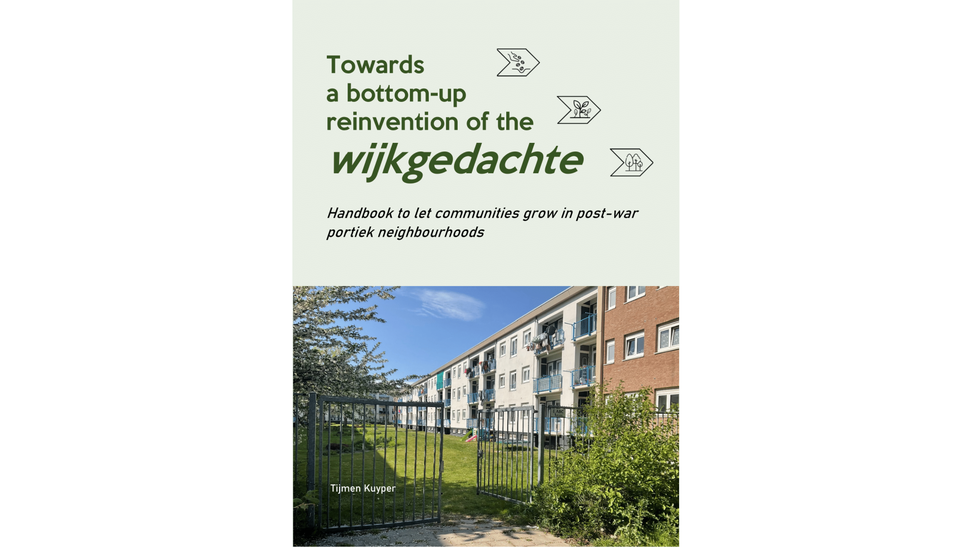

"It feels like a great honour to participate in thinking about someone's home. Your home is something very intimate. Poor design can cause stress, leading to health problems." Tijmen wrote the theses for both his bachelors on the topic of 'cohousing': sharing your kitchen, living room, and/or garden. "It can be a partial solution to loneliness, housing shortage, energy costs... But it is also risky! Architects sometimes underestimate the complexity of designing for collective residences. In such cases, cohousing is built which doesn't incorporate lessons from research and pre-existing projects."

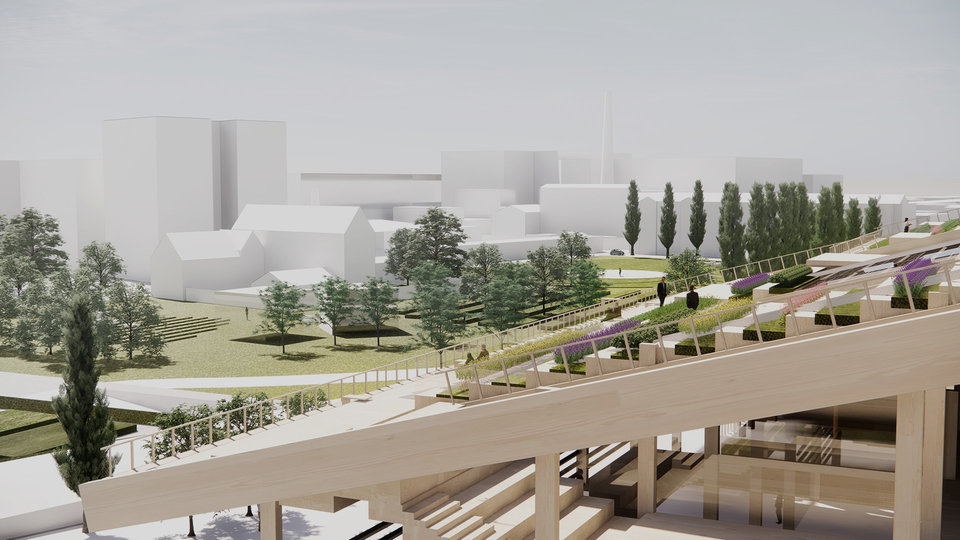

During Birgit's course, Tijmen's group was tasked with designing cohousing for elderly residents of the neighbourhood Moerwijk Zuid, The Hague. But during the research phase, they discovered that even lonely people become attached to their home and neighbourhood. "We visited a dinner group. One of them already lived in a cohousing project. The rest were jealous, but absolutely did not want to leave their lonely flat!" Tijmen understands their reaction. In the past, he lived as a property guardian and saw up close how a neighbourhood, a community, was lost. To prevent such a loss, he created a detailed strategy for a gradual transition to a more social and healthier neighbourhood.

What Tijmen is essentially trying to do is revive the original plan for Moerwijk. The plan emphasized the so-called 'spirit of the neighbourhood', the sense of community. "Developing this spirit takes time, and comes from the residents. The architect only creates the right conditions." Tijmen continues this mission by starting a consultancy with retired architect Phillip Krabbendam, whom he met during this course. Together, they supervise cohousing projects. "Because when such projects fail, you create an unhealthy environment. But success actually leads to thriving and healthy communities!"

Eline Koes: bring back the ‘social’ in social housing

During an internship for her Hbo studies in Zwolle, Eline already worked on the design for a care home. She also spent two summers working as a domestic help for elderly: "grateful work, and I was drawn to the target group." So it was no coincidence that she ended up joining Birgit's course. By the second week, her team was already entering The Hague to observe and interview. "The neighbourhood, Loosduinen, is a special case. It is green and calm, but nevertheless a troubled neighbourhood: small flats with poor insulation, litter, noise pollution... yet interviewing residents of all ages revealed that everyone wanted to stay!"

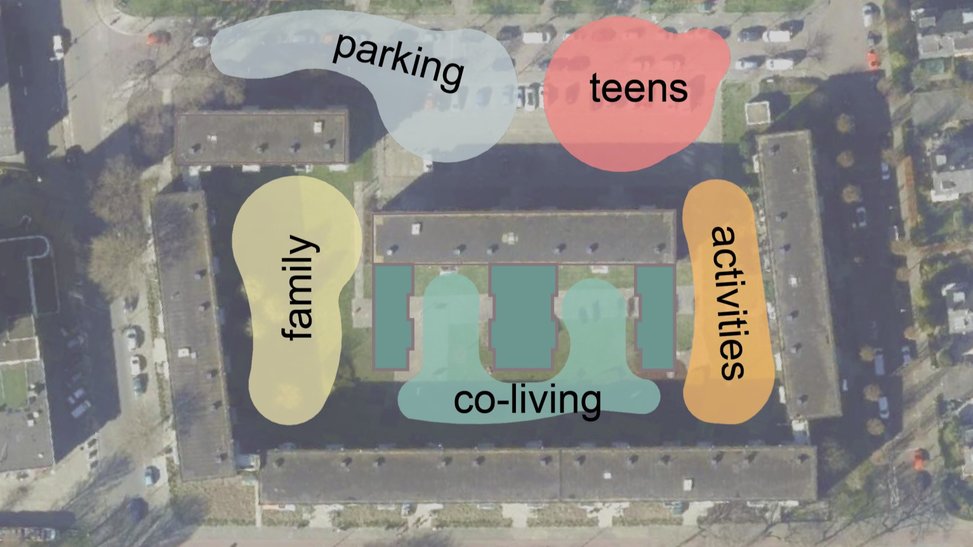

Eline decided to focus on a block of social housing apartments around a large courtyard. It houses a variety of focus groups, including many elderly people. Eline: "Contact between these groups is extremely important." She soon noticed that immediate neighbours knew each other well, but there was almost no mixing between the units. "This created a lot of fear and misunderstanding among the residents. What are those status holders doing here? Why is that dementia patient acting so weird? Can't those ex-addicts go somewhere else?" But there were also examples of a better way. The man who was so vehemently against status holders turned out to be close friends with his Turkish-born neighbour!

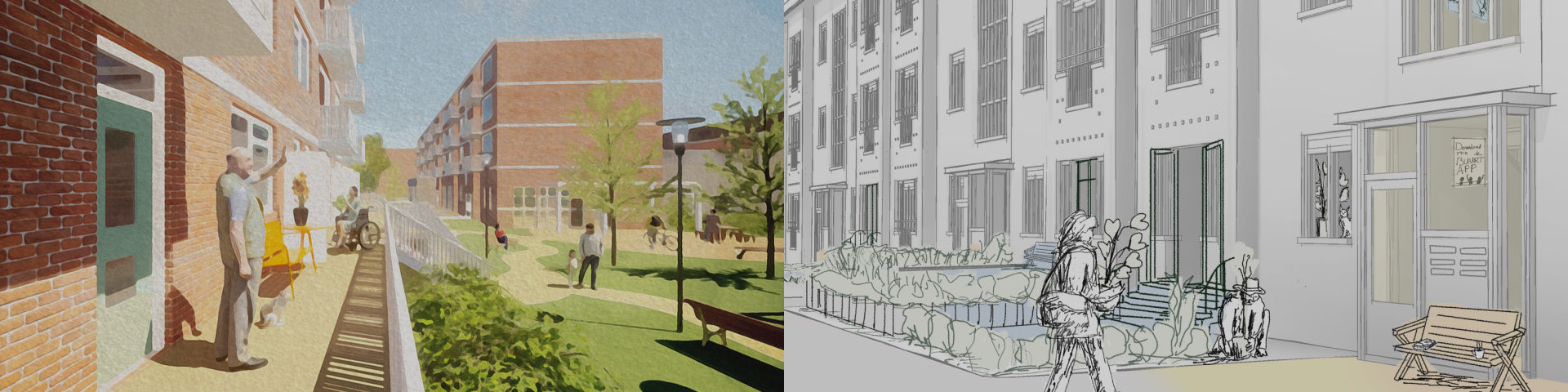

Based on these experiences, Eline developed a whole series of recommendations. "A crucial step is to create a buffer zone between private and public space, so in this case between the house and the large courtyard garden. For example, a raised forecourt." She also recommends making homes on the ground floor wheelchair-friendly, and building new cooperative housing blocks in the courtyard that are suitable for the elderly. This will encourage activity and prevent loneliness. "It was nice to see that the housing association paid attention to the advice - they really want to change!" Eline was so inspired that she is now graduating on the topic 'designing for healthier ageing'.

This story is published in January 2024.

Birgit Jürgenhake

Tijmen Kuyper