Urban food and material chains contain huge amounts of valuable materials, a considerable proportion of which is still lost as waste. Take phosphorus for example, an indispensable and irreplaceable nutrient. Whilst the global supplies of phosphates contained in ores are steadily diminishing, we all excrete them in our urine where they return to the environment via sewers, mixed with other substances. Researchers from TU Delft demonstrate an alternative in the sea container used as a mobile urban living lab as was previously on display at the AMS Institute in Amsterdam.

Arjan van Timmeren, professor of Environmental Technology and Design, is investigating how materials ‘flow’ through cities and how the lifecycle of materials – from raw material to waste to raw material – can be made more efficient. One of these urban materials flows begins in the toilet. Urine and excrement disappear into the sewer system every time we flush. Once in the sewer they form part of a mixed wastewater flow that goes to a wastewater treatment plant.

Mobile mini-lab

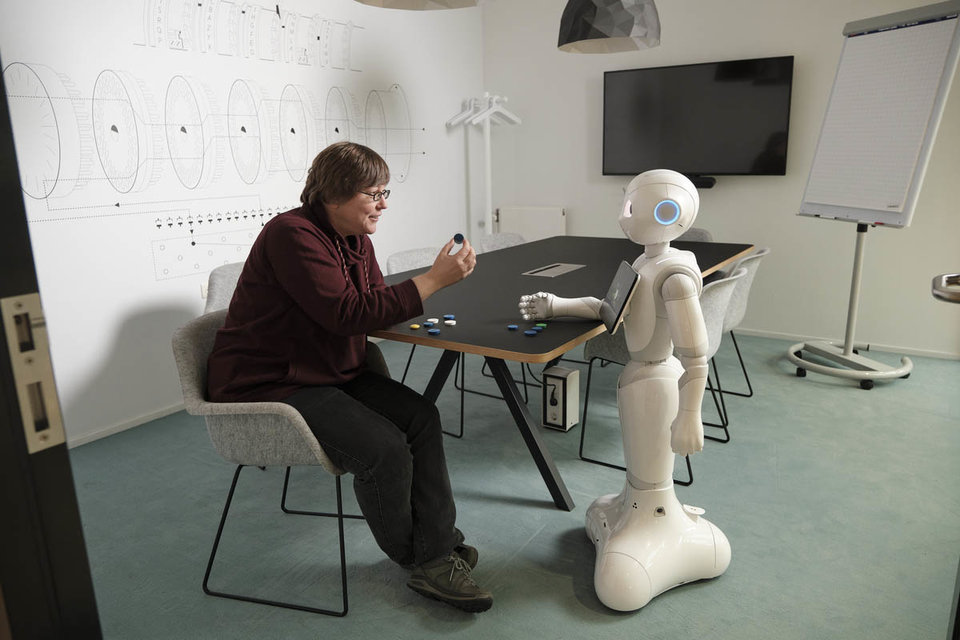

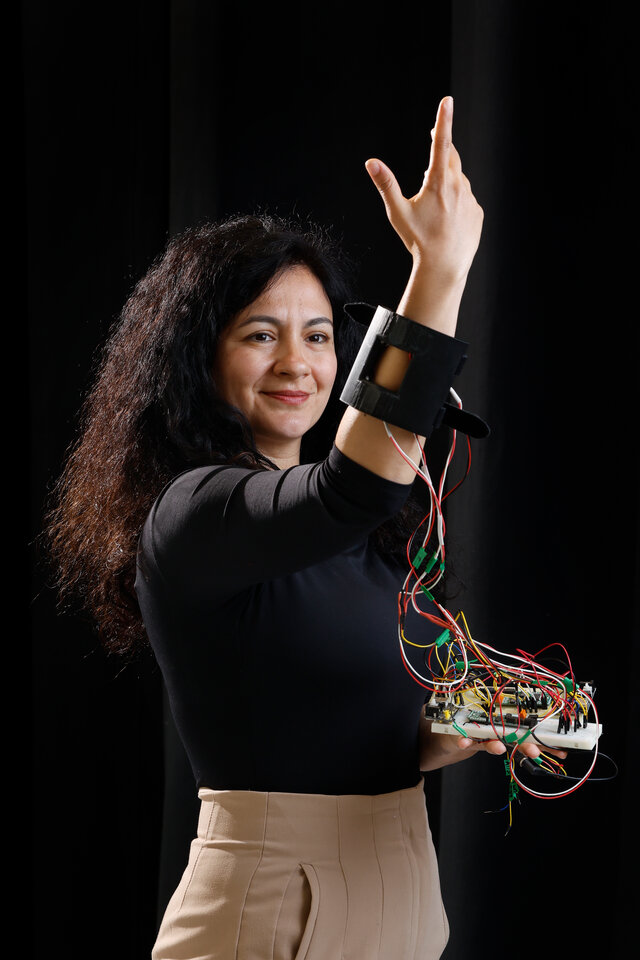

The process of wastewater treatment has been the subject of research and optimisation for decades, as we seek how to remove as many harmful substances as possible from the waste stream while recovering as many valuable materials as possible. “At the scale of the treatment plant, in some places phosphates are already being recovered in the form of struvite, a solid fertiliser”, explains Van Timmeren. “For a European research project that the Faculty of Architecture and the Built Environment is participating in, I asked microbiologist Monica Conthe to help design a smaller-scale modular treatment and recycling process that can also be moved from place to place.” The result is a mobile mini-lab in a shipping container that literally shows very clearly how you can also take measures at the source to recycle nutrients.

Two to three carrots

Manufacturer Laufen supplied two special toilets that separate the urine from the flushing water and the faeces. Conthe coupled these together with a waterless urinal to a bioreactor and a vacuum evaporator to recover various valuable nutrients plus high-quality water using a process of nitrification and distillation. Besides phosphorus, the plant also recovers nitrogen and small amounts of potassium and boron. Harmful substances such as drug residues and hormones are in principle removed during the process. “The plant can handle 30 litres of urine a day”, she explains, “that's enough to deliver around 10g of phosphorus. Next to the container we have a small greenhouse where we use the recovered nutrients to feed various crops. This enables us to also study what effects different proportions of fertilisers have on different food crops.”

In this way the urine of city dwellers can be used right away and on location to grow fruit and vegetables that the same city dwellers eat and then re-excrete.... and with the least possible burden on the environment. The result: a safe, small-scale recycling system that helps make cities circular. According to Conthe's calculations, one pee provides enough nutrients to grow two to three carrots. “Scaling up this demonstrated process will enable us to go some way to meeting urban food needs. For example using forms of urban farming.”

Showcase

The specially decorated shipping container is a real eye-catcher. And you can clearly see what is going on in the ‘P-lab’ thanks to the sliding glass panels on two sides, that can be completely opened, enabling the plant to serve as a showcase for applied science. Conthe: “It is our express intention to demonstrate how you can extract valuable materials before they enter a waste stream and need to be recovered at a later stage, or they become lost in the environment entirely where they may also form a threat to the natural balance. In this way we hope that everyone who visits us will stop to consider processes that remain unseen by the majority of people.”

Bulk user

Creating awareness is one of the goals of this European project that started in 2018, says Van Timmeren. “CINDERELA, that stands for New Circular Economy Business Model for More Sustainable Urban Construction, uses demonstrations and test plants to show just what is possible. And that it works. Our mobile lab is one of six demo plants.” Other examples are located in Spain, Slovenia and Croatia, where materials recovered from waste streams are being used as building and construction materials, for example for road surfacing and to make street furniture. Even the slurry that remains after the wastewater treatment process is being trialled as a raw material for the building industry. According to Van Timmeren, that makes it even more important that all important substances such as phosphorus – which the EU has designated a critical raw material – are recovered before they become trapped in building materials. In addition: “The building industry is a bulk user of raw materials and produces a relatively large amount of waste. Without a circular building economy it is impossible to have a circular economy. What we need now are good practices that can be scaled up.”

Amsterdam and Delft

The sea container has spent well over one and a half years (2019-2020) on the 'Marineterrein' site of the AMS Institute in Amsterdam. The Amsterdam Institute for Advanced Metropolitan Solutions (AMS Institute) is the knowledge institute shared by TU Delft, Wageningen University & Research and MIT in Amsterdam where, in close cooperation with the Municipality of Amsterdam, urban challenges are being tackled with experiment-driven scientific research, education and entrepreneurship. The idea was that visitors to the Marineterrein would be able to participate in the experiment by using the toilets. Unfortunately, this was only partially successful due to Covid and the lockdowns. “We did manage to test the facility to our satisfaction, including with visitors in the periods between the lockdowns”, Monica Conthe explains.

The sea container is now located in Delft. Visitors to the Science Centre will soon be able to go to the toilet there for a scientifically responsible wee. We are also assessing whether the sea container can be taken to various festivals this summer. As Monica Conthe explains, “We are curious to see the extent to which festival-goers would voluntarily use it and how many nutrients this would generate.” A facility of this size can also easily be installed in building basements. “The yield can be used right on site, for example in an adjacent vegetable plot.”

![[Translate to English:] [Translate to English:]](https://filelist.tudelft.nl/_processed_/0/b/csm_Header%20afbeelding%20InDetail%20-%20Stefan%20Buijsman%20-%202_01_8b72583971.jpg)