The paint reveals the master

In the end, even the most famous painting is just paint on a canvas, says art historian Joris Dik. Studying the paint can expose forgeries, magically conjure up hidden paintings, and allow you to eavesdrop while a Rembrandt or a Picasso practices his craft.

‘Da Vinci did not paint the shadows in the Mona Lisa’s face with a darker hue, but by stacking layers of almost transparent paint,’ explains Joris Dik, professor of materials in art and archaeology at TU Delft. Dik is an art historian, but also a materials scientist. A proponent of the arts in the world of science, but he feels completely at home there. ‘In art, it often revolves around the concept, the image, the idea and the beauty of a painting. In fact, many art enthusiasts actually find technical knowledge disconcerting. That has always surprised me. Because it’s the material that provides us with great insight into the creative process.’

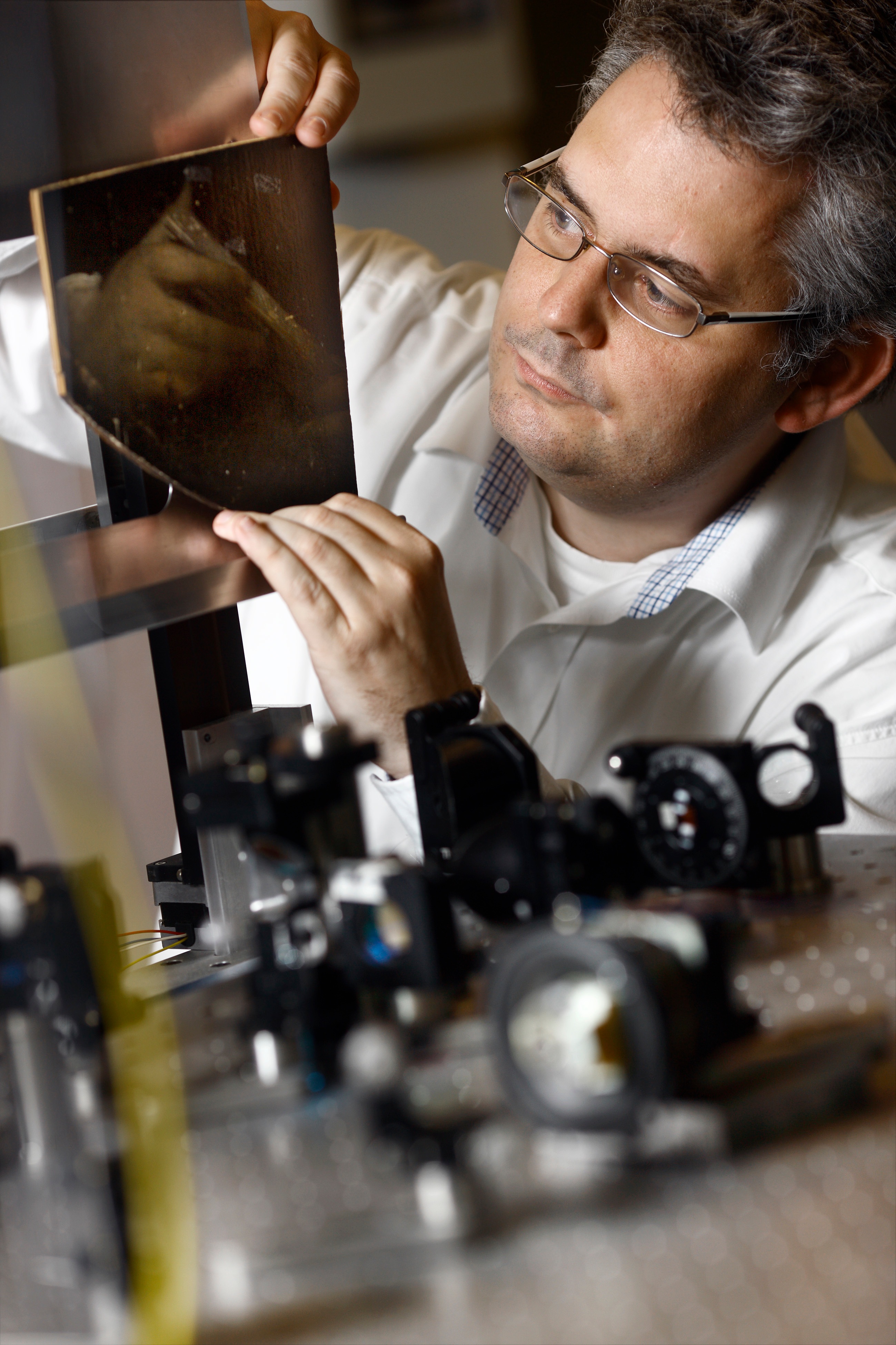

In the past decade, Dik has made a name for himself by introducing the art world to X-ray fluorescence spectroscopy. ‘XRF’ can ‘dissect’ a painting without damaging it. The analysis technique individually reveals different chemical elements in the paint, often pigments.

It turns out there is a woman’s face resembling the potato eaters hidden behind Van Gogh’s painting Pasture in Bloom (1887), for example. Van Gogh painted over it because canvasses were expensive. Rembrandts Saul and David (ca. 1660) appears to have been simply cut in half, Dik reveals. ‘Perhaps the paintings earned more money if sold separately?’ Saul and David were reunited, but XRF research has shown that they probably shifted a few millimetres from their original position vis-à-vis each other.

‘Every major museum has its own scanner now,’ Dik says. Nowadays they are important to confirm the authenticity of old masters. ‘Last year another forged Frans Hals was discovered.’ It concerned the painting Portrait of a Gentleman, sold by Sotheby’s for almost ten million euros in 2011. The canvas had surfaced in 2008 and after many art experts examined the painting, it was attributed to Frans Hals based on the typical brush strokes, the composition and the paint that was used.

Your own synchrotron

Painting research can be conducted with much greater precision with synchrotron radiation, emphasises Dik. ‘It enables you to see exactly where the elements are in a layer of paint. It also provides you with depth, a 3D image. Moreover, you can look at many more elements.’ Dik has already travelled once with a painting to the particle accelerator in Geneva, which generates high-quality synchrotron radiation. ‘But the measuring time is limited, of course. And you don’t want drag around valuable paintings too often.’

In two or three years Dik hopes to have a mobile ‘mini-synchrotron’ at his disposal. Dutch physicists from Eindhoven and Delft are building one, with the support of KNAW in a large research consortium called Smart*Light. The most important applications are in materials science and health care, but Dik is participating as well. ‘Art history is a small field and the world of art a small market. So I have to persuade technologists from completely different scientific disciplines that we’re an interesting niche for the new research technique.’

That’s why he appears regularly on TV. Dik is one of the experts in the popular television series and touring theatre show ‘Het geheim van de meester’ (‘The secret of the master’). And he can be frequently seen on shows such as DWDD, Pauw and RTL Night to talk about the authenticity of paintings. ‘It’s not that I have an urge to be on TV, but as an art historian you’re not building dikes or inventing new medicines, which are things everyone immediately sees the need for. You really have to continue explaining the importance of art history and promoting you work.’

When Smart*Light is ready, Dik would like to study Pablo Picasso’s cubist painting The Old Guitarist. There appear to be several versions beneath it, each possibly more abstract. If you can manage to ‘peel off’ these layers, then you can follow Picasso’s thoughts. ‘Essentially, you’re eavesdropping on one of the greatest innovators of painting,’ Dik says.

Palimpsests are on Dik’s wish list as well. These are written parchments from the early Middle Ages, before the age of paper. The valuable, dried animal skins were scraped off multiple times in order to be written on again. ‘The university library in Leiden has a 32-page-long palimpsest that has visible text underneath it,’ Dik says. ‘But it’s too vague to decipher.’ Dik hopes to make the text visible with the Smart*Light by zooming in on a specific element. ‘Who knows, this may lead to us discovering the oldest Dutch text.’

Strange partners

Dik is always in search of new alliances and new analyse techniques. For example, he is currently studying the use of optical coherence tomography (OCT) with Jeroen Kalkman. OCT is an infrared technique that’s making deviations in the retina visible in increasing detail. ‘An OCT scan enables you to make a kind of cross-section of the retina. We use it to study layers of varnish. For example to monitor with great precision the removal of a layer of varnish during a restoration. More and more, restoration studios are resembling surgery theatres.’

Dik has also discovered common interests with the Netherlands Forensic Institute (NFI). ‘There are important parallels between art history and forensic research. A forensic investigator is often given objects and asked to explain what happened to them.’ The NFI discovered that XRF is a good way to reveal traces of blood or sperm when the usual UV techniques fail, for example on a deep-black background. And XRF can also reveal traces of gunpowder that have been ‘washed out’ or that are hidden behind a fresh layer of paint.

In collaboration with the printing company Océ 3D, Diks’ research group printed a number of old paintings. The Jewish Bride by Rembrandt now graces a wall in the ME building at TU Delft. The copy is much more ‘real’ than a poster. The bottom layer was printed in plastic and provides the copy with relief and thick brush strokes and craquelé. ‘The red of the dress is not deep enough,’ the connoisseur Dik points out. ‘We haven’t managed to imitate the colour well, because that also depends on certain pigments in the bottom layer.’ But it’s the lustre that really betrays the fact that it’s a fake, in Dik’s opinion. ‘The lustre has the same height everywhere, whereas it varies in the real painting. A PhD candidate is currently studying the differences in lustre in layers of varnish, and how they affect paintings.’

What needs to be done to make a more realistic 3D copy? ‘More than anything, we want to learn more. How quickly do layers of varnish discolour? How fast does such a layer wear away and how does the lustre change as time passes? And a print enables you to create an image of the effect of a restoration. Make no mistake, discussions about what is really original and whether it should be restored can be extremely heated in the world of art. So we can contribute by giving an idea of the result.’

Who is Joris Dik?

His grandfather and uncle restored old paintings. The craft, the studio and the smell of oil paint fascinated Joris Dik (1974). He was well on his way to continuing the family tradition while he studied art history. But during an internship at the J. Paul Getty Museum (Los Angeles), Dik discovered that it was especially the preliminary research preceding restoration that captivated him. Which pigments did the painter use? Have they discoloured? Were any changes ever made to the painting? If so, when and why? He followed up his education with PhD research on Naples yellow. ‘The oldest pigment in the history of art. It can be found on all of the tiles in India from four thousand BC.’ Dik took samples from artworks from different times and places and analysed the composition. This created a ‘historical atlas’ of Naples yellow that helps during restorations and investigations to determine authenticity. In 2003 he started working as a materials researcher at TU Delft. He has been Antoni van Leeuwenhoek professor since 2010.

![[Translate to English:] Copyright Geheim van de Meester](https://filelist.tudelft.nl/3mE/Onderzoek/Check%20out%20our%20Science/Headerafb/jo1.jpg)