In the derelict public spaces of St. Louis, USA

In the deprived neighbourhoods of Belfast, Northern Ireland

In the bustling streets of Chennai, India

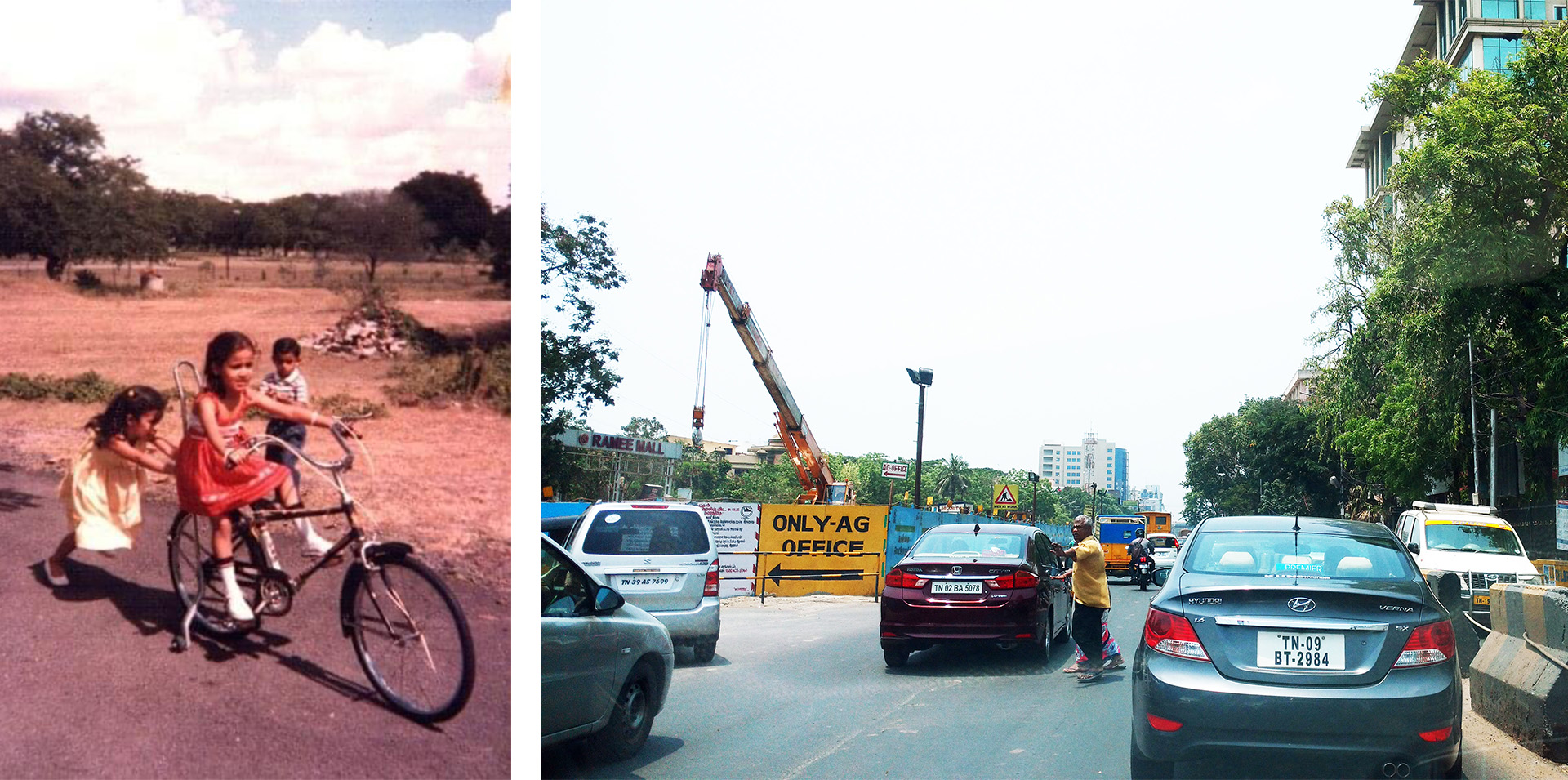

Everywhere she looks, Associate Professor Dr Deepti Adlakha finds connections between urban design and health. She has spent her life not just studying these connections, but experiencing them first-hand. “I remember biking to school when I was very young. Now, when I visit my home city, the cyclists appear to be risking their lives.”

Deepti joined the Faculty of Architecture and the Built Environment in the summer of 2023. Professionally, she aims to channel the faculty’s expertise in engineering and design into public health research. But the move to the Netherlands is more than just a career transition, it is a chance to practise what she has been preaching for years. Deepti: “I was drawn by the successful public transport system and the cycling and walking infrastructure. Now, for the first time in my life, I can consider going car-free.”

I had to be driven to school, strapped in for my safety. But during the holiday, I experienced the abundance of nature.

She grew up in Chennai, a dense megacity in southern India, and navigated its streets every day to go to school. But as the years passed, the roads became increasingly congested. Eventually, she had to be driven to school: “being strapped in for my safety”. In contrast, during the summer holidays Deepti escaped to her grandparents’ home in a rural region where, as she put it, she “experienced the abundance of nature”. In short, she noticed how surroundings could either promote or hinder independence and mobility.

Who is hit the hardest when the monsoon strikes

Deepti recalls an experience that made her acutely aware of the power of urban design. While pursuing her bachelor’s degree, she did a six-month internship in the city of Mumbai. She was working at the office on a stormy day at the height of the monsoon season when the entire staff was suddenly sent home. It was only 2 PM. “I remember waiting by the bus stop for an hour, and then I just started walking.” Before long, she was wading through waist-high water, with cars floating by down the street. She still had 8 kilometres to go.

I waited for an hour and then just started walking. Before long, I was wading through waist-high water.

Mumbai is built on reclaimed marshlands and has lost much of its original green spaces, making the city particularly vulnerable to floods. The experience led Deepti to broaden her scope to the scale of neighbourhoods, cities, and regions. “I became more aware of the connections between sites and their surroundings, and the impact of inequity: those with the least, face the greatest risks. They often live in places that are more prone to disasters and have fewer resources to recover.” These lessons would guide her throughout her career.

Urban health around the globe

Deepti pursued her master’s in urban design on a Fulbright Fellowship at Washington University in St. Louis, USA. She had read about St. Louis as the site of a failed building scheme, infamous for its derelict buildings and racial segregation. But “visiting these neighbourhoods and actively engaging with local communities truly revealed the profound impact that design can have.” Deepti studied parks and green spaces by organising focus groups with residents. The accompanying literature research revealed further proof of the powerful link between living environment and health. “In St. Louis, life expectancy between north and south neighbourhoods might differ as much as twelve years.”

Next, Deepti took her growing skills and expertise on the connections between cities and health and applied it in Chennai. Her PhD research was the first of its kind to extend the field of healthy cities in India. “During fieldwork, I studied informal settlements and their access to daily necessities such as work, education, transportation, shopping, and healthcare.” The outcome was a walkability scale adapted for the Indian context, now freely available online. By answering a range of questions about a neighbourhood, you can rank the area on its walkability and spot areas of improvement. The tool is used by civic organisations, public health researchers, physiotherapists, and urban planners in cities across India.

As a postdoctoral researcher, Deepti moved to Belfast, Northern Ireland, which was constructing a major greenway. She studied its impact on the health and social well-being of vulnerable populations. Deepti employed techniques like Go-Pro’s and GPS technology to track people’s activity. What resonated with her is how much visible and invisible change was sparked by the greenway. It not only resulted in more outdoor activities, but also gave rise to numerous festivals and community-led projects such as volunteer clean-up initiatives, community gardening, and art workshops. Deepti: “The greenway is now listed in tourist maps as a destination. More proof of the power of urban design.”

Deepti used technologies like Go-Pros on bikes (left) to study how the residents of Belfast made use of the newly constructed greenway (right).

Everyone deserves a healthy place to live

In recent years, Deepti spent much of her time researching the escalating issue of lifestyle-related diseases, such as obesity, diabetes, and heart disease, and the growing epidemic of loneliness and social isolation. She led parallel studies in Colombia, USA, Saudi Arabia, and India. While the analysis of the results is still ongoing, an alarming trend is already emerging: children are spending more time indoors and watching screens instead of playing outside. And the COVID-19 pandemic only exacerbated this trend. Deepti: “The lack of parks and playgrounds, especially in dense urbanising regions of the world, is a critical concern.”

Many useful findings are not being applied… Everyone in a position of power has the ability to advocate for and defend the rights of the vulnerable.

Currently, Deepti leads the Global South initiative of the ‘Global Observatory of Healthy and Sustainable Cities’, where she is developing evidence-based urban planning policies. “Many useful findings are not being applied. I want to change that, especially in the Global South.” Recognising the climate crisis as the foremost threat to health and well-being, Deepti underscores the urgency to implement healthy city initiatives and policies to effectively tackle associated complex challenges. “It is not just researchers who can make a difference. Everyone in a position of power has the ability to advocate for and defend the rights of the vulnerable—particularly our fundamental right to live, learn, work, and play in an environment that is healthy by design.”

This story is published in February 2024.

More information

Read about Deepti’s research and findings on walkability in Chennai in this paper, titled ‘"Can we walk?" Environmental supports for physical activity in India’.

Or read about the methods used in Belfast and the impact of its greenway in ‘Assessing the Impact of a New Urban Greenway Using Mobile, Wearable Technology-Elicited Walk-and Bike-Along Interviews’.

You can find more information about the Global Observatory of Healthy and Sustainable Cities by visiting their website.