Women are consciously opting for mechanical engineering

In June 1921, exactly a century ago, Stanny Koopman was the first woman to graduate from the mechanical engineering programme in Delft. It would take another 40 years before Diny Lammens would replicate that feat, becoming the second woman to graduate in 1959. Nowadays, dozens of women graduate every year from the Mechanical Engineering master’s programme, and that number is rising steadily.

In 1915, Stanny Koopman joined what was then called the Technical Institute of Delft to study mechanical engineering. The idea was that she would subsequently work as a technical expert in her brother-in-law’s patent office, but that never happened. She married civil engineer Wim Swaan in 1921 and left with him for the Dutch East Indies. There she worked in journalism and taught mathematics at a secondary school in Semarang. Later, back in the Netherlands, she continued to teach mathematics and mechanics. In 1959, she was invited to present Diny Lammens, the second female mechanical engineer, with her engineering degree.

Flapping apron

Unfortunately, the education superintendent didn’t want to give Koopman the day off for this, because the final exams were about to start. This can be read in a congratulatory letter Koopman wrote to Lammens. In it, she says that ‘I now know more about my husband’s profession, irrigation, than mechanical engineering’. She describes how she had once worked at Stork: ‘which is to say I walked around there, because I wasn’t allowed to touch anything! I also wore a large blue apron so my skirt wouldn’t get stuck in the machine, even though skirts were tight in those days whereas the apron flapped around.’ She also recalls the commemoration song she wrote for the second anniversary of the DVSV, the Delft student association for women, which merged into DSC in 1976.

Fortunately, female graduates are not such a rare sight these days; in recent years, their number has hovered around 15 per cent of the total. This wasn’t the case in the 1980s. Els van Daalen, alumna from 1987 and still affiliated with TU Delft, was one of three female graduates in her year. This male-female ratio sometimes resulted in strange situations. ‘I became the commissioner of education at study association Leeghwater,’ says Van Daalen, ‘which was great, but beforehand there was a meeting about whether it would be any fun to have a girl on the board. The debating society’s room was called the Gentlemen’s room, and they weren’t willing to change that either.’ When Jolien Kroon graduated 25 years later, the percentage was still below 10 per cent, so she received a special welcome at the student association’s intro weekend: ‘I was fresh out of high school and arrived in Delft by train and bicycle and walked down Mekelweg. There was an endless queue of boys. Then someone shouted through the loudspeaker: that must be Jolien, come up to the front.’

She never saw any of this as a problem. ‘It’s just the way it was, and I was aware of the fact beforehand. It’s because the faculty at Delft was bigger than the one in Enschede and there would be more women that I went there. And I lived in a student house with nine other girls. But it wasn’t long before I met a group of friendly boys with whom I could study well.’

| Diploma year | Men | Women | % Women |

| 2002 | 142 | 5 | 3% |

| 2003 | 186 | 11 | 6% |

| 2004 | 170 | 10 | 6% |

| 2005 | 305 | 20 | 6% |

| 2006 | 179 | 11 | 6% |

| 2007 | 320 | 29 | 8% |

| 2008 | 366 | 24 | 6% |

| 2009 | 347 | 20 | 5% |

| 2010 | 446 | 28 | 6% |

| 2011 | 557 | 50 | 8% |

| 2012 | 537 | 61 | 10% |

| 2013 | 612 | 56 | 8% |

| 2014 | 491 | 51 | 9% |

| 2015 | 391 | 42 | 10% |

| 2016 | 288 | 32 | 10% |

| 2017 | 389 | 64 | 14% |

| 2018 | 346 | 50 | 13% |

| 2019 | 341 | 53 | 13% |

Number of Mechanical Engineering BSc diplomas awarded by diploma year and gender

Monique van der Hoeven, who graduated in 1989, even saw it as an advantage. ‘I liked studying among men because they’re uncomplicated. Working a lot with men during your studies makes it easier to hold your own in what is still a male-dominated society,’ she says. ‘I didn’t have any negative experiences at the time either. Once, all the ladies walked out of a lecture because the lecturer kept saying “gentlemen”. But you can encounter these kinds of situations at work as well.’

At the interface of medicine and technology

Van der Hoeven is still happy with her choice of study. ‘I had my doubts about medicine, but as soon as I saw that you could work on things like prosthetic hands for children at mechanical engineering, I thought: ‘That’s what I want to make.’ For my graduation, I did measurements on the muscles in the shoulder girdle, as part of a large study on dislocations.’ She has always continued to work at the interface of medicine and technology, as a product manager, innovation advisor and currently at the research financing institute ZonMw. She recommends it. ‘Socially speaking, women are often service-oriented, and the combination of service and technology creates many opportunities to do appealing work, whereas the humanities side probably has less to offer in terms of future prospects.’

In Angela Janus’s case, it was her father who inspired her to go to TU Delft in 1991. ‘Children have a clear perception of women’s professions, such as teaching. My father went to work at Shell Pernis, which I found very exciting and a bit mysterious. I wanted to study something technical so I could work in the industry,’ she says. ‘After I graduated, there was a shortage in the labour market, just like now, so there were a lot of different opportunities open to me.’ She became a trainee at Stork and is currently an independent project and change manager. ‘A lot of subjects that are touched on during your studies come in handy later on. For example, you may not do much technical drawing yourself, but it’s good to have some knowledge of it.’

Once, all the ladies walked out of a lecture because the lecturer kept saying “gentlemen”.

Learning to think analytically

Kroon, who works as a continuous improvement specialist at FrieslandCampina, is also pleased with the breadth of the programme. ‘You learn to think analytically and you can apply that everywhere in the business world. That may also apply to other engineering programmes, but you can’t go wrong with mechanical engineering.’ She also sees mechanical engineering as having a positive reputation. ‘I took on a difficult engineering study and showed that I could master the material. So there’s never any doubt about whether I can handle a certain job intellectually.’ Is it really that difficult? ‘You must have an affinity with it, plus a dose of perseverance,’ says Kroon.

Van Daalen also has good advice for prospective students: ‘My advice to girls is: don’t think that you’re not good enough. Don’t be discouraged by men who seem to know more. You’re just as capable,’ she says. ‘Choose your specialisation carefully, so you can prepare yourself for it in your choice of subjects,’ Janus adds.

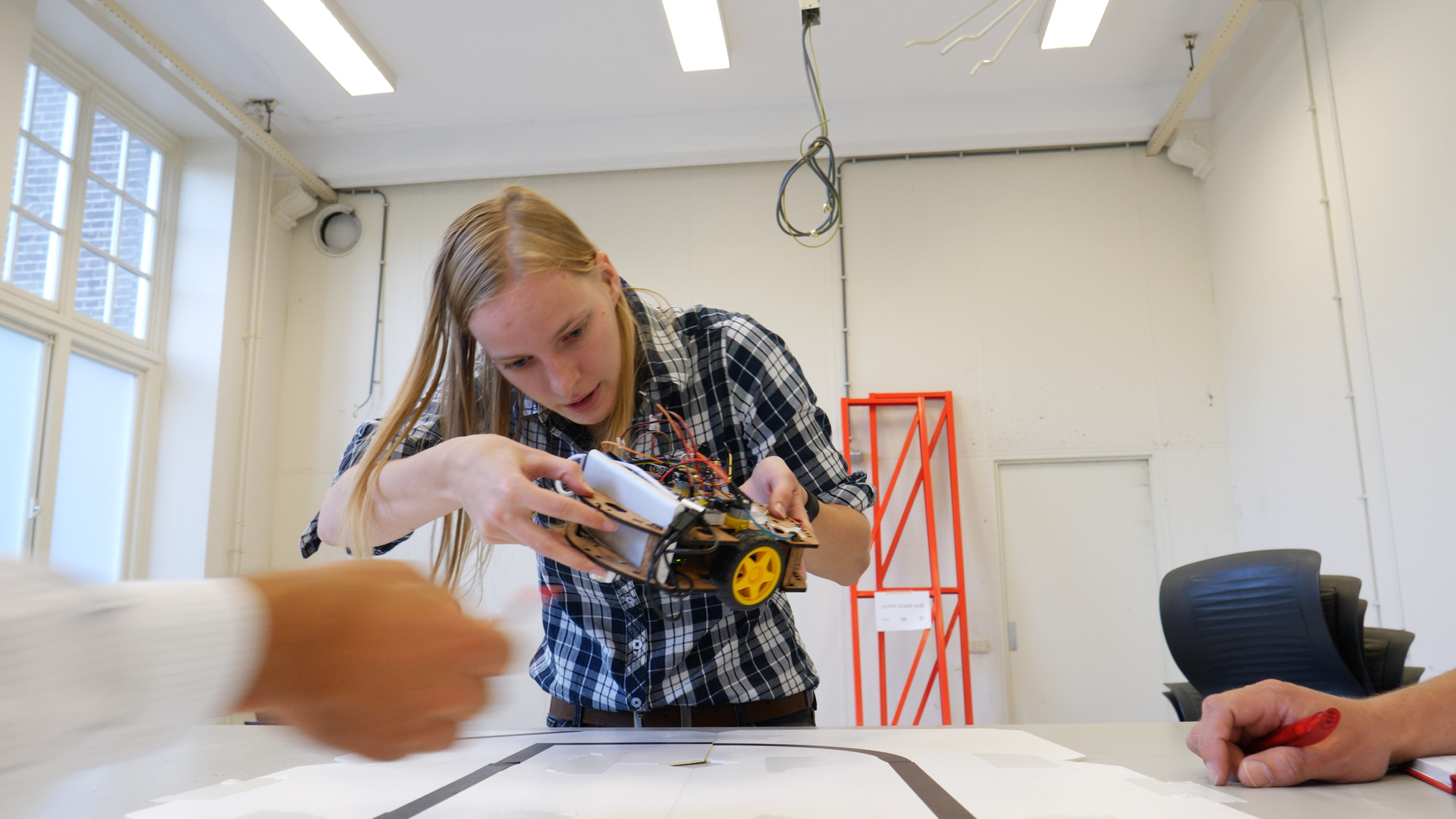

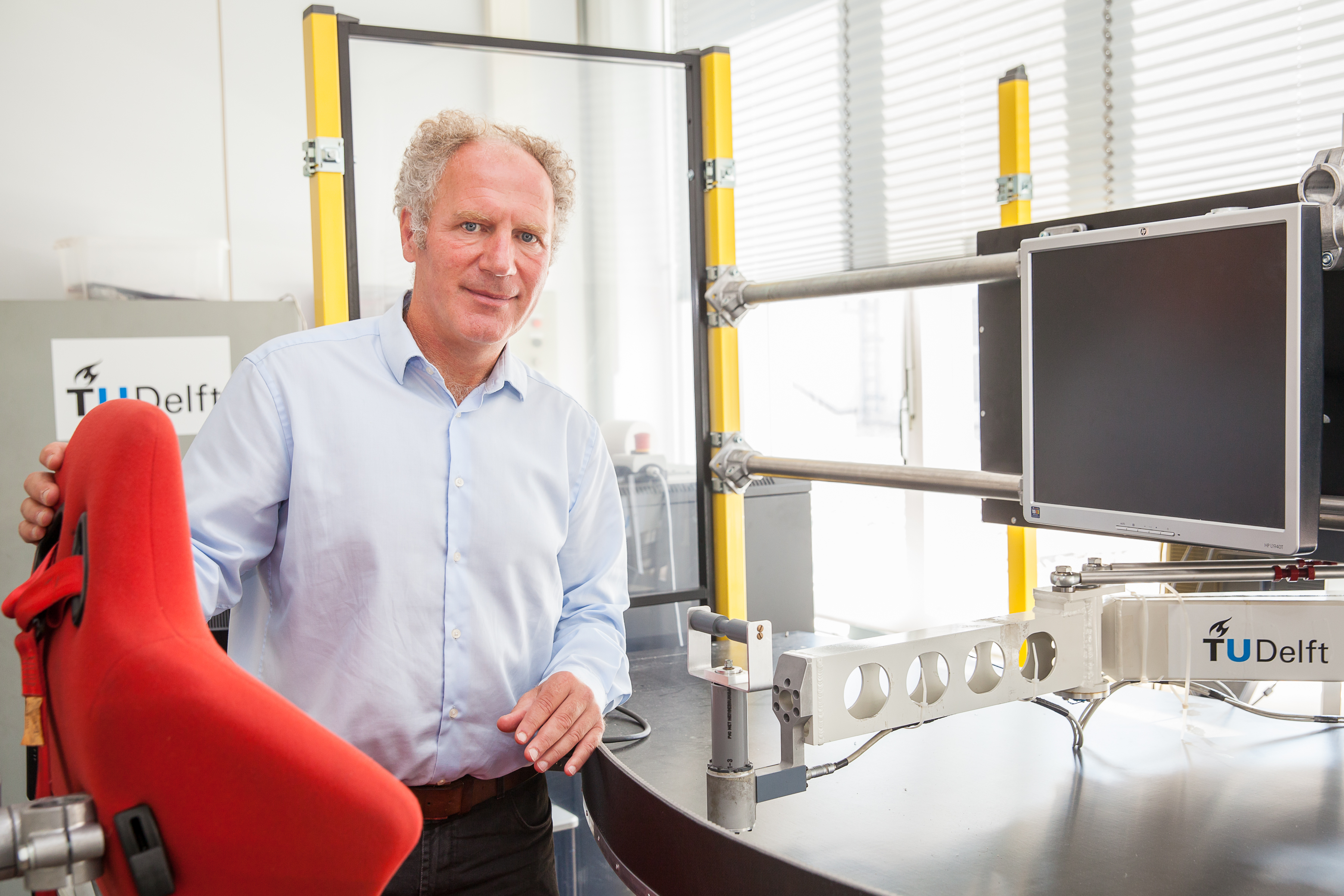

‘Our female students are generally better than the male ones. They’ve already gone through so much self-selection,’ says Frans van der Helm, professor of biomechatronics and human-machine control. His colleague Jenny Dankelman, professor of minimally invasive surgery and interventional techniques, agrees: ‘I think the fact that we have a smaller number of female students is because mechanical engineering is a very conscious choice by women. That’s why they’re highly motivated and work really hard. They also bring a different atmosphere to the faculty, which is positive.’

On a pedestal

Kroon would like to see more women in engineering, particularly in mechanical engineering. ‘Most boys and men are a lot nicer in an environment where there’s a bit more of a healthy ratio. I was put on a pedestal at the time and everyone knew who I was, but there were a lot of boys who were too shy to talk to girls because they didn’t encounter them very much. These extreme ratios don’t do anyone any good. We don’t necessarily have to make it 50/50 right away, but let’s aim for 30-70 to start with.’ That shouldn’t be a problem according to Dankelman: ‘There’s plenty of female talent out there.’