From 2027, various products in the EU must have a Digital Product Passport (DPP). This passport contains information about the origins of raw materials, among other things, and the degree to which materials can be reused in a circular manner. TU Delft scientist Jolien Ubacht is conducting research on where companies can obtain this data and how they can incorporate it into the passport. Despite the significant administrative work involved, she also sees opportunities for both companies and consumers to contribute to increased reuse of materials.

With the Green Deal, the EU has taken an important step towards a sustainable and circular future. A key component of this is the Digital Product Passport (DPP). With this passport, companies within the EU are obliged to report on aspects such as product composition, the origin of raw materials, and the recyclability of components at the end of their lifespan. Initially, the passport will apply to products such as cars, electronics, and textiles, with more products to follow later.

Sustainability of the supply chain

The aim is to create a more sustainable supply chain, explains researcher Jolien Ubacht. "The passport will, for example, indicate the conditions under which a raw material, such as a metal, was produced or mined. But also, which parts can be recycled. Increased circularity is not only good for the environment, it is also necessary for the recovery of scarce resources. When you manage to reuse more materials, you need to import fewer new ones, making the EU less dependent on critical raw materials from other countries." My personal motivation to contribute to this? The images I have seen of dumped materials in nature and open landfills in countries where discarded materials are shipped to. There has to be another way."

Collecting data from every component

One of the projects Ubacht is working on from the faculty of TPM focuses on collecting data in the supply chain of cars. "A car consists of a large number of components, such as electronics, an engine, seats, a battery. These components are in turn made up of individual materials such as plastics, textiles, and metals. An automobile recycling company needs to know exactly where all these materials come from, what raw materials they consist of, and to what extent they are circular. With a passport, the materials can then be prepared for reuse at the end of a car's lifecycle. In our research, we are looking into what data companies must make legally available for the passport and which parties in the chain can provide this data."

Design choices for the digital environment

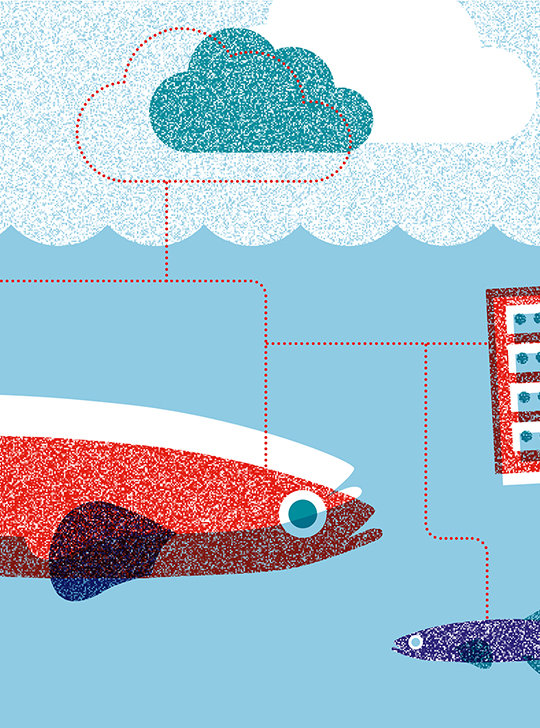

Another important aspect of the passport is the ICT issue. In which digital environment do you collect all the data and how do you present it? Ubacht: "You can make various design choices for this. A central database and website for all products would of course be great, but in practice, it is not feasible due to the large amount of data that needs to be collected. It is better to look at a digital platform per sector or product, where parties exchange their product-specific data. Companies then maintain their own data, which is linked via this platform with standardized protocols (APIs). This requires data standardization and collaboration throughout the supply chain. In Delft, we are mapping out the design choices for sharing data for the digital product passport."

Educating consumers

Consumers can also gain access to the digital passport to make sustainable choices. So you also have to think about communication to the outside world. Ubacht: "As a company, in addition to the mandatory reporting to authorities, you can also give your customers access to information. This can include information about the origin, but also about locations where a device can be disposed of or repaired. To make this communication effective, you have to make it as accessible as possible. With a QR code or RFID label, a kind of chip in the product, you ensure that consumers can easily access product information with their phones."

Monitoring and control of implementation

According to Ubacht, the Digital Product Passport is pre-eminently a TPM subject. In addition to a technical and management aspect, there is also a governance component. Who, for example, is responsible for monitoring and overseeing implementation? Ubacht: "This is something individual countries will have to arrange themselves. The big question is how to do so. One option is to leave control to market parties. For the import of products, you already have customs. You could also give organisations involved in recycling an additional oversight task."

In the design phase, much more consideration should be given to the reusability of parts or materials at the end of their lifespan. A lot of research is already being done on this within the Delft Circularity lab of TU Delft, where knowledge from various disciplines comes together.

Significant administrative burden

Although sustainability and circularity are increasingly important to many companies, not every company is equally enthusiastic about the introduction of the passport, according to Ubacht. "This is mainly due to the enormous administrative burden it brings. You have to go through the entire chain and then also make all the data suitable for sharing. Additionally, some companies are hesitant because of the commercial sensitivity of information. Furthermore, you depend on the willingness of parties in the supply chain to share data, which really is a challenge."

Scrutinizing the supply chain

At the same time, unlocking information also offers opportunities for companies, Ubacht continues. "For example, to show the outside world that you have nothing to hide and attach great value to a 'clean' product. Nowadays, consumers who want to buy sustainable products really appreciate this kind of information. It also provides an opportunity to thoroughly examine the partners you work with in the chain. If a supplier pays little attention to sustainability or is unwilling to share data, you can choose to switch to a party that does. This can also bring other benefits, such as smoother import rules or lower import taxes."

New way of designing

According to Ubacht, the introduction of the Digital Product Passport could also lead to a revolution in product design. "In the design phase, much more consideration should be given to the reusability of parts or materials at the end of their lifespan. A lot of research is already being done on this within the Delft Circularity lab of TU Delft, where knowledge from various disciplines comes together."

Vehicle to connect disciplines

Ubacht finds the combination of sustainability and ICT particularly interesting. "You need knowledge of digital techniques for data sharing, of product composition, and the conditions under which parties are willing to share their data. The Digital Product Passport is truly a wonderful vehicle to connect these disciplines. What product data do you need, where do you get it from, how do you process everything, and how do you ultimately present it to the outside world? ‘It's a puzzle, but that's what makes it so enjoyable for me as a researcher. Even after the introduction of the passport, there are still plenty of questions to answer. How do you monitor materials once they are recycled, how do you measure the effect of the Digital Product Passport, and will it actually change our consumer behaviour? Plenty of subjects to delve into!’

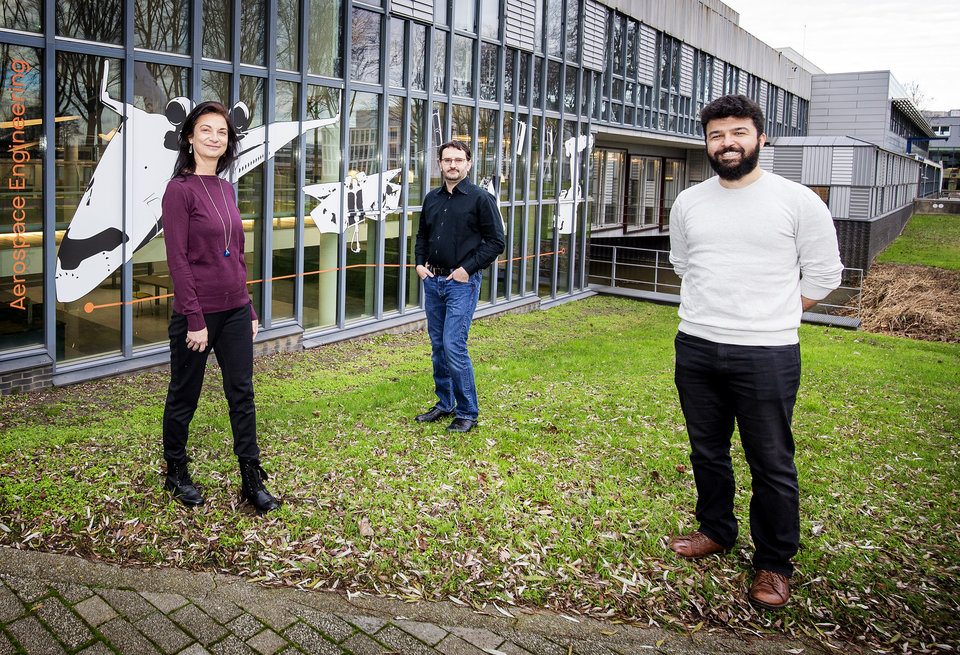

About Jolien Ubacht

Jolien Ubacht is an assistant professor at the faculty of TPM at TU Delft. She is fascinated by digital innovations that support societal challenges such as the UN Sustainable Development Goals. She takes a comprehensive systems engineering perspective, which entails looking at the stakeholders involved, the technical design choices to be made, and the governance of the digital innovation upon implementation. She is involved in the CIRPASS project, a collaborative initiative to prepare the ground for the gradual piloting and deployment of a standards-based Digital Product Passport (DPP). Another circularity project she is involved in is DATAPIPE. It aims to help the Customs Administration of the Netherlands and the Ministry of Infrastructure and Water Management of the Netherlands to be better equipped to meet their responsibilities in the context of the circular economy by having access to relevant data for monitoring.