Dr. Birgit Jürgenhake from the Faculty of Architecture and the Built Environment asks the master students in her graduation studio to spend a day riding around Delft in a wheelchair. On another day, they wear special glasses that limit their vision. Students even spend a week living in a care home, where they participate in daily activities. For Birgit, these experiences are essential: "Only through interaction with the elderly do we learn what they need from their place of residence."

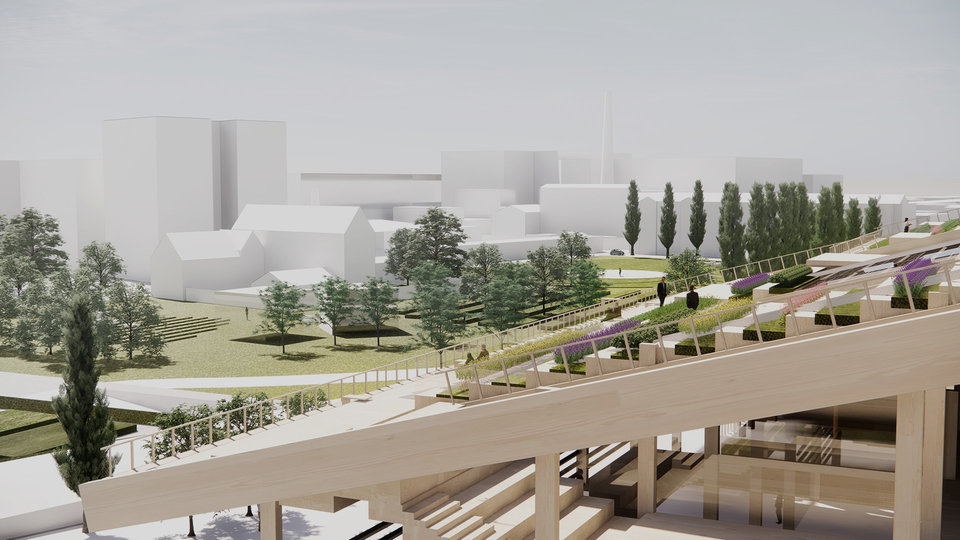

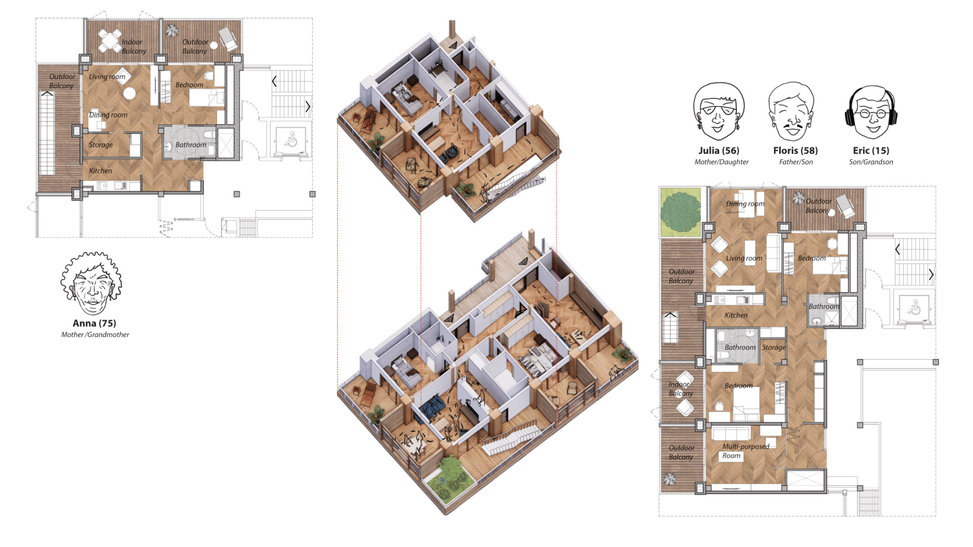

According to Birgit, architects and designers are the foremost practitioners of preventative healthcare. Her graduation studio ‘Designing for Care’ challenges students to design housing which contributes to the physical and mental well-being of elderly residents. A great example is the thesis project of Chu Yu Liang, who created a hypothetical design for a multigenerational housing complex in Binkhorst, The Hague.

Finding the balance between two cultures

Chu Yu: “I learned that the Dutch state no longer builds nursing homes, and encourages the elderly to stay in their houses as long as possible, even though these might not be suited for that purpose. At the same time, the housing crisis means that more and more young people are forced to keep living with their parents. With these developments in mind, why shouldn’t we try to redesign houses to make living together an acceptable solution?”

Chu Yu was raised in Taiwan, which traditionally has a very different approach to the concept of housing the elderly. “You are generally expected to live with your parents. For the past decades, the trend was: young workers migrate into cities to get a job, and their parents move in with them for the convenience of nearby facilities.” Shortly after finishing her studies, Chu Yu actually helped to design a ‘senior daycare centre’, which is exactly what it sounds like: a place where working-age Taiwanese bring their parents during the day to prevent accidents at home. After a few years of work experience, she decided to move to Delft to continue her education.

How to make housing suitable for all generations?

That is how Chu Yu ended up in Birgit’s graduation studio, which involved spending three days in a Dutch elderly residential complex. “I found that these elderly really loved being near others, even if there was no interaction involved. During meet-ups, many would join just to watch and listen.” She spotted several design flaws. “One resident could not enter the garden because a single raised threshold blocked her way. Also, I noticed that, due to lack of storage space, the staff were forced to leave assistive equipment in the corridor. It gave the residents a depressing sense of living in a hospital.”

Partly based on this experience, and partly on further research, Chu Yu created a set of essential guidelines for multigenerational housing. Examples for indoor spaces include: having two entrances, shrinking the distance between bedroom and toilet, installing sliding doors, and clearly indicating the location of the bathroom. And for the communal area: intersecting routes, constructing an atrium, making walking paths continuous, and providing ample green space. In this way, Chu Yu hopes to find a middle ground between the traditional Taiwanese and Dutch models: between total independence and total dependence. “I personally believe there is much potential in the concept of multigenerational housing.

This story is published in February 2024.

Meer informatie

You can read more about Chu Yu and her work at her website.

Or read the entire thesis and see all the designs by going to the repository.

Dr.ir. Birgit Jürgenhake