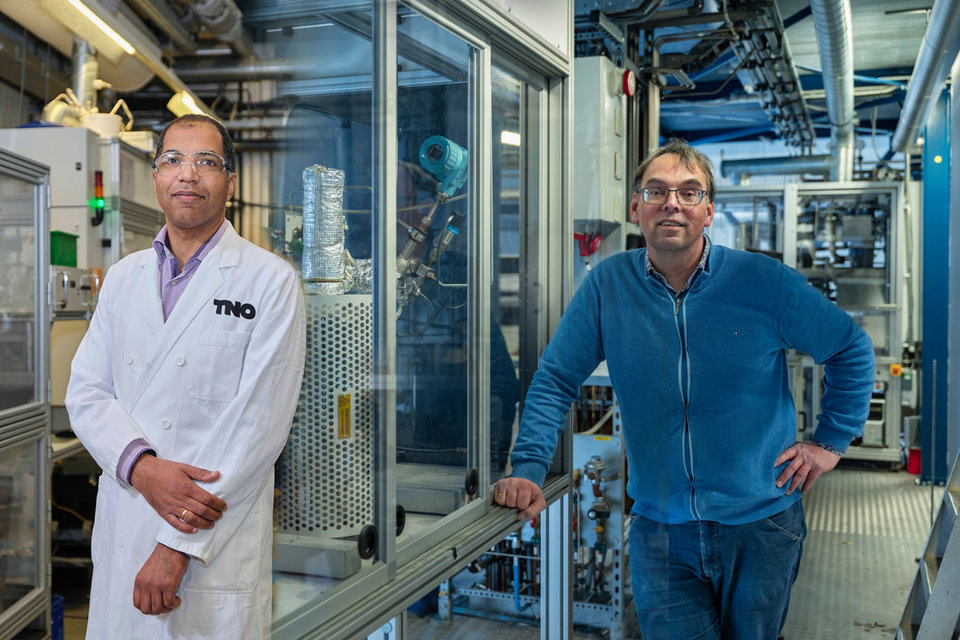

Any kind of sensing, human or not, unveils similarities. Ice and metal may both feel cold. The sun and an apple may both appear to be red. For Francesco Fioranelli, specialised in using radar technology for the classification of objects, there is little difference between a fighter jet manoeuvring at tens of kilometres distance, or an elderly person staggering through a room.

Francesco Fioranelli is fascinated by perceiving the environment beyond the senses available to us as a human being. ‘Radar is an ideal technology for distinguishing objects and their movements, without touching them,’ he says. ‘By bouncing electromagnetic waves of the surface of an object, we can measure its location and speed, when near or far, in rain, fog and darkness.’ As an assistant professor in the Microwave Sensing, Signals and Systems group, Francesco mostly focusses on increasing the intelligence of radar – creating algorithms that use Machine Learning classification to make sense of the patterns of the radar data. Originally, he applied his knowledge for the more traditional surveillance purposes, such as ensuring safe routing for aircraft and vessels. But he was quick in realising that the continued miniaturization and cost reduction in radar technology has opened up many new opportunities.

Not such a big step

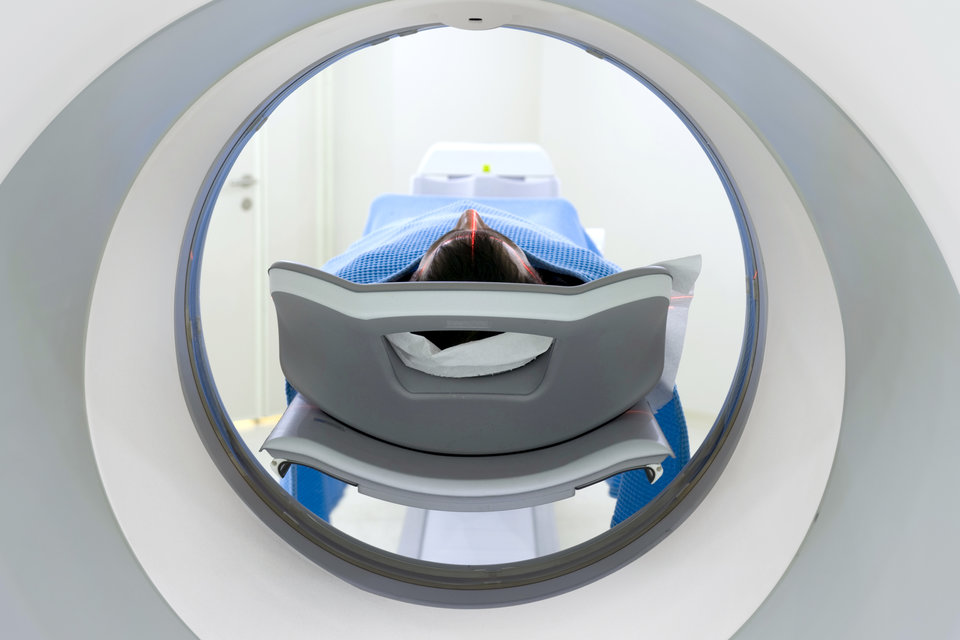

One of these opportunities is the application of radar for tracking your health in your home environment, raising the alarm before you are so unwell that you need highly specialised and expensive care. It is not such a big step from airspace surveillance as you may think. ‘With some tweaking, the algorithms I used for processing radar data to identify drones at several kilometres distance are just as applicable to tracking the motion of a person in a room,’ Francesco says. ‘By looking at radar data, we can infer a lot of useful information about the wellbeing of a person. How that person moves and walks, for example, and in what activities he or she (no longer) engages.’ This is very useful information from a medical perspective, as research has shown that walking speed, step size and general level of activity are strong indicators of your state of health. The idea is for such a radar system to be embedded into a corner of a room, or even an armchair, rather than having people carry around some measurement device that they may find cumbersome or even forget about entirely. ‘In our group, we develop the tools to prove these applications in a laboratory setting,’ Francesco says. ‘After that, other parties are needed to continue development for real-world applications.’

Using radar to track your health in your home environment is about raising the alarm before you need highly specialised and expensive care.

A new way of looking, even for radar

Having only arrived in the Netherlands about a year ago, Francesco already wrote, and was recently awarded, an NWO Klein grant (“RAD-ART”) for investigating a very novel methodology for processing radar data. ‘The majority of methods in the literature try to interpret radar data as images,’ he says. ‘They therefore use algorithms that are based on, or at least similar to, those used for image processing. But that is not necessarily how radar works. Radar is a stream of pulses being send and received in a constant sequence.’ In his RAD-ART project, Francesco will therefore look at Artificial Intelligence techniques that are inspired by the study of sound, speech and music. The primary focus of this research is the analysis of human motion in a domestic setting – to see if with some tweaks, these techniques will help in training a radar system to understand the large variety in human movements. But the same algorithms can also be used for other applications such as surveillance – think of a drone hovering somewhere and then suddenly accelerating towards an airport. Francesco: ‘We are venturing into very new territory. It could well be that in four years we conclude that it doesn’t work.’

By analysing radar data of human motion as if it were music or speech, rather than images, we are venturing into very new territory.

A tree won’t cross the road

A perhaps somewhat better-known, but still quite new application of radar is its use in autonomous cars. By integrating and fusing multiple types of sensors – such as optical cameras, laser ranging (lidar) and radar – autonomous cars can operate safely under any weather circumstances and darkness. Francesco and his colleagues work on the interpretation of these radar signals to get an awareness of the surroundings. Again, it is about object recognition. ‘These radar data look like blobs,’ Francesco says. ‘We want to, for example, be able to say if these blobs represent a big truck in the opposite lane or perhaps a car using your lane to overtake another car. Likewise, the car needs to be able to distinguish a tree or lamppost next to the road from a person, as the latter may decide to cross the road at any moment.’ One way the researchers try to improve this situational awareness is by training a radar system using data obtained with optical cameras. ‘We are working towards a laboratory setup where we have a camera and various radar boards looking at the same scene, collecting data simultaneously,’ Francesco says. ‘The department is also considering buying some target simulators. Rather than having to go through the cumbersome process of building real-life scenarios, these devices can simulate how radar echoes will look for a given radar and several targets, speeding up data-acquisition tremendously.’

We want to raise the situational awareness of car radar by training these systems using data obtained with optical cameras.

Radar to the rescue

Francesco is convinced that his research can have a positive impact on the world, but also clear about radar not being the answer to everything. ‘Radar may never be able to beat high-quality medical devices,’ he says, ‘but it may offer a cheaper and less invasive solution, allowing a person’s health to be monitored outside of a hospital setting.’ It will take some years for radar to make it into our homes and cars, and those of our ageing parents. Until then, when in traffic, you may at times still have to rely on your fighter jet-inspired evasive manoeuvres.

Text: Merel Engelsman | photography: Frank Auperlé