Geodata can provide a better match between the supply of construction waste and the demand for building materials, according to doctoral research by Tanya Tsui. Material exchanges could improve if we have more accurate knowledge on where buildings are going to be demolished and where new construction projects are coming up. “If that is clear, you have a good starting point.”

Closing the materials cycle is a major sustainability challenge for the construction industry, but also a difficult one. The reason is that demolition and construction projects in a certain area do not happen at the same time, creating a mismatch in supply and demand. Material exchanges could improve if we have more accurate knowledge on where buildings are going to be demolished and where new construction projects are coming up. “Existing research regarding the circular economy ignores these kinds of spatial aspects, while they are very important,” Tsui says. “We need to know which locations could play a role in it and we have to determine what is the maximum distance materials can travel.”

Sources of geodata

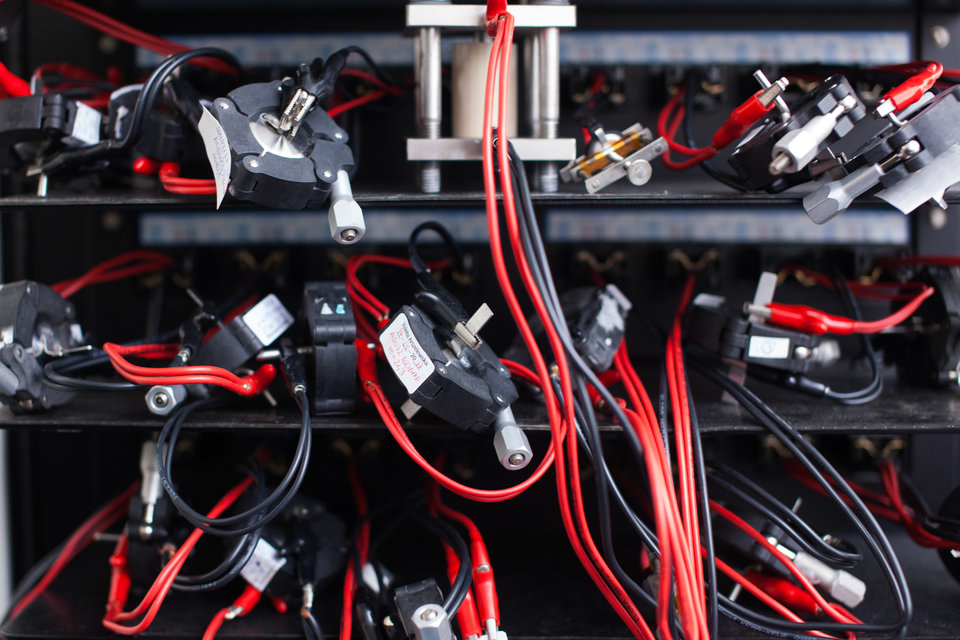

To make that happen, she built a model for which she used two important new sources of geodata. Statistics from the Landelijk Meldpunt Afvalstoffen (LMA) - the Dutch National Waste Registry - show the locations where reusable construction waste goes. Forecast data from the PlanBureau voor de Leefomgeving (PBL) – the Netherlands Environmental Assessment Agency – show on a map where future construction materials will be released and where they will be needed: future construction sites.

Based on the data, Tsui could calculate the ideal ‘cell size’ within which materials should circulate. For building materials, such as channel boards, beams and roof tiles, she arrives at a cell size of about 7 kilometers. For materials such as plastics and metals, that distance is greater: 20 to 25 kilometers. It shows that the ideal scale of the circular economy is fairly compact, and dependent on industry.

We have to determine what is the maximum distance materials can travel.

Wooden buildings

Will the materials cycle ever be completely closed? “No,” Tsui says. “Even if we were to reuse all demolition materials, it's not nearly enough to meet new construction demand.”

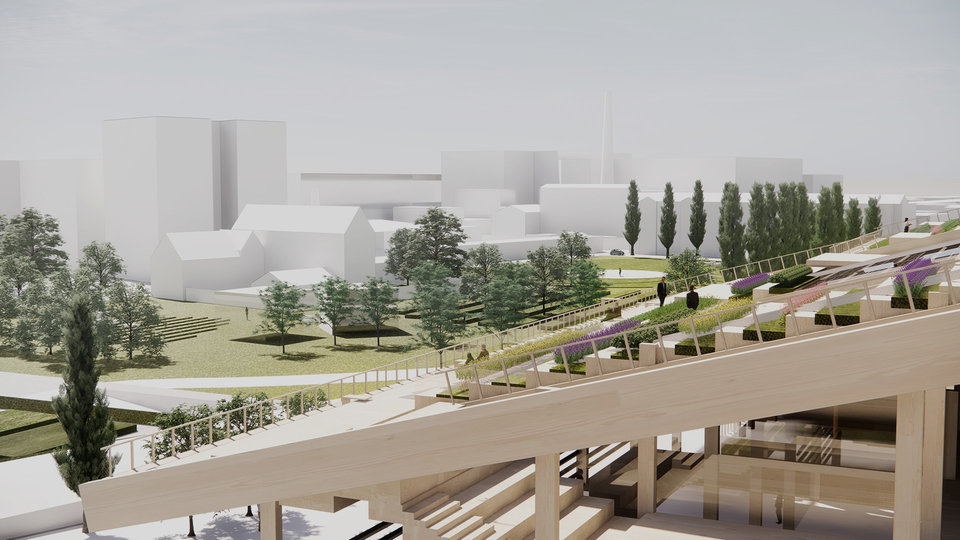

This is especially true for reusing wood from construction, according to a case study she did. In it, she zoomed in on timber recycling in the Amsterdam region. The capital's ambition to build large numbers of sustainable timber homes clashes with another ambition: the large-scale reuse of waste materials. The explanation is simple: there are too few demolition-ready timber buildings in the region to meet the demand for wooden beams, floors and paneling.

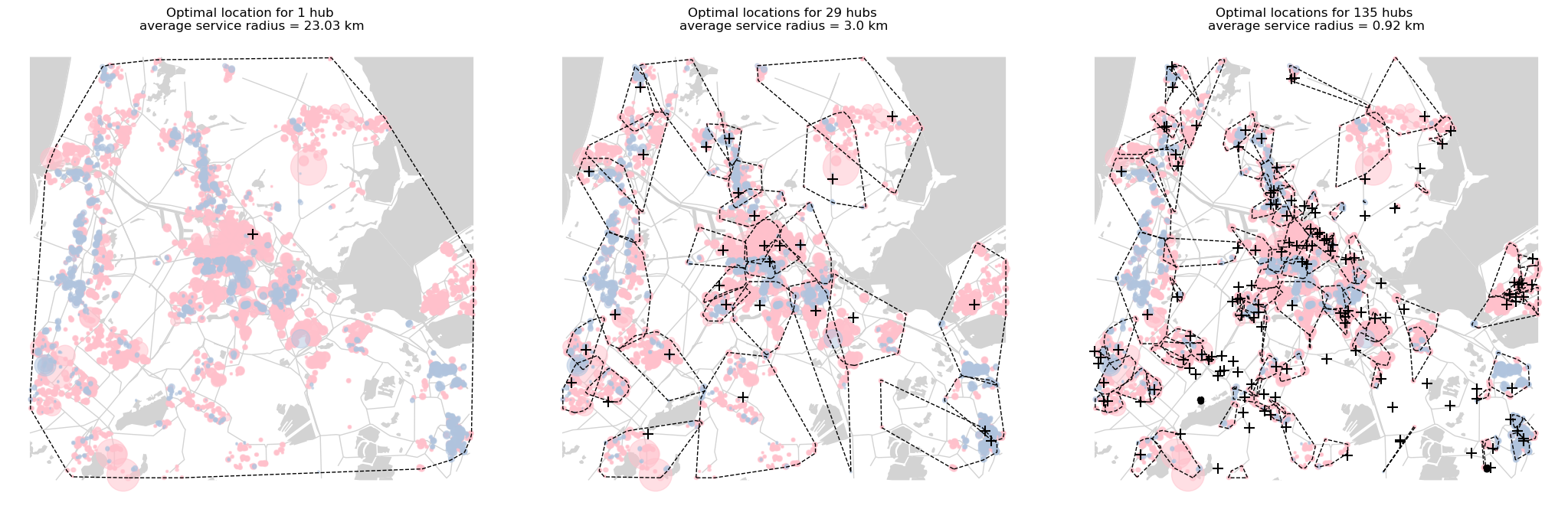

The case study also shows that the service area for collection, storage and distribution of reusable wooden building components should be at most three kilometers. According to the same calculations, that would mean that 29 timber hubs would be needed in Amsterdam alone. Such a finely-meshed network would also be ideal from a cost perspective.

Currently, the number of hubs for receiving, storing, processing and distributing building materials is still limited. Establishing a covering network of hubs geared to future construction and demolition developments is best organized at the provincial or national level, according to Tsui. “Based on data analysis, you could make a comparison between locations: where will new houses be built, which industrial sites should stay or disappear and where should material hubs be located? If that is clear, you have a good starting point.”

This story is published: March 2024

More information

On 5 December 2023 Tanya Tsui defended her PhD thesis ‘Spatial approaches to a circular economy: Determining locations and scales of closing material loops using geographic data’.