Alex de Rijke appointed Professor of Timber Architecture

A Way With Wood

As a child he loved making treehouses. As an architecture student he admired structures in timber most of all. He started out as a practitioner by redesigning and rebuilding his mother’s house, using discarded plywood. “That made sense because I needed material, didn’t have any money and couldn’t bear waste.” As of November 2023, Alex de Rijke is professor of Timber Architecture at TU Delft Faculty of Architecture and the Built Environment. “I’ve always liked making and I see direct connections between making and thinking, practice and theory.”

As founding director of the London based firm dRMM Studio (1995) and as a teacher at some of the best schools for architecture De Rijke (1960) has pioneered the development and application of engineered timber in public structures, cross-laminated timber (CLT) in particular. His appointment ensues from the faculty’s ambition to further the worldwide utilisation of timber and other bio-based as well as recycled building materials. “I am delighted to be offered this role and to contribute to research and teaching as member of a Bio-based Design Team. Many students here are already interested in bio-based design and are eager to learn more.”

Bigger picture

An obvious reason to use timber on a grander scale is that, if re-used rather than incinerated, it continues to hoard carbon. Furthermore, bio-based resources are regenerative, not extracted from limited natural resources. Processing and applying them offers considerable environmental advantages when compared with the production and application of steel and concrete.

Wooden buildings support their occupants’ well-being, physically and psychologically.

De Rijke has a bigger picture in mind, though. Apart from storing carbon and creating a great construction material, trees stabilise soil, prevent erosion, benefit natural water cycles, provide shade, food and habitat for diverse species, produce oxygen and even reduce air pollution. Wooden buildings support their occupants’ well-being, physically and psychologically. And then there is the tactility and warmth of wood… there‘s so much to like.” By pursuing the large-scale mixed forestry required to meet a massive timber demand, the world can reap all kinds of global and local benefits. “But for every tree cut, we should be planting at least four. It’s all about upping the ante.”

Discovering timber products

De Rijke has Dutch roots. His parents emigrated to the UK before he was born. “They grew up during the Second World War and were incredibly resourceful people. My mother was a farm girl. My father could make and repair anything, using only what was lying around. I guess we were raised on that mentality combined with my mother’s understanding of nature, trees in particular.”

When he was studying architecture in the early 1980’s concrete and Le Corbusier were all the rage. “Whilst I loved his plans I didn’t like concrete, and thought his manifesto, although provocative, was all rhetoric and style-based. After I graduated I discovered Swiss and German timber products and techniques, applied them in our first projects in the UK and developed the practice from there. I’ve come to look at the history of architecture not as a series of styles, but as a series of typology and material choices.”

Serious option

dRMM’s radical redesign of Kingsdale School, London, dating from 2002, included the first large-scale use of cross-laminated timber in the UK. His team had to overcome much prejudice against this innovative building material, De Rijke recalls. “We had to persuade the government, the local authorities and the insurance company of its qualities and benefits in order to gain permission. This included translating German DIN-standards into English.” The design subsequently gained praise for its positive effects on pupils’ well-being and has served as an exemplar. “Many schools, in the UK and in Europe, have since been built in timber, positioning CLT as a serious option next to steel and concrete.”

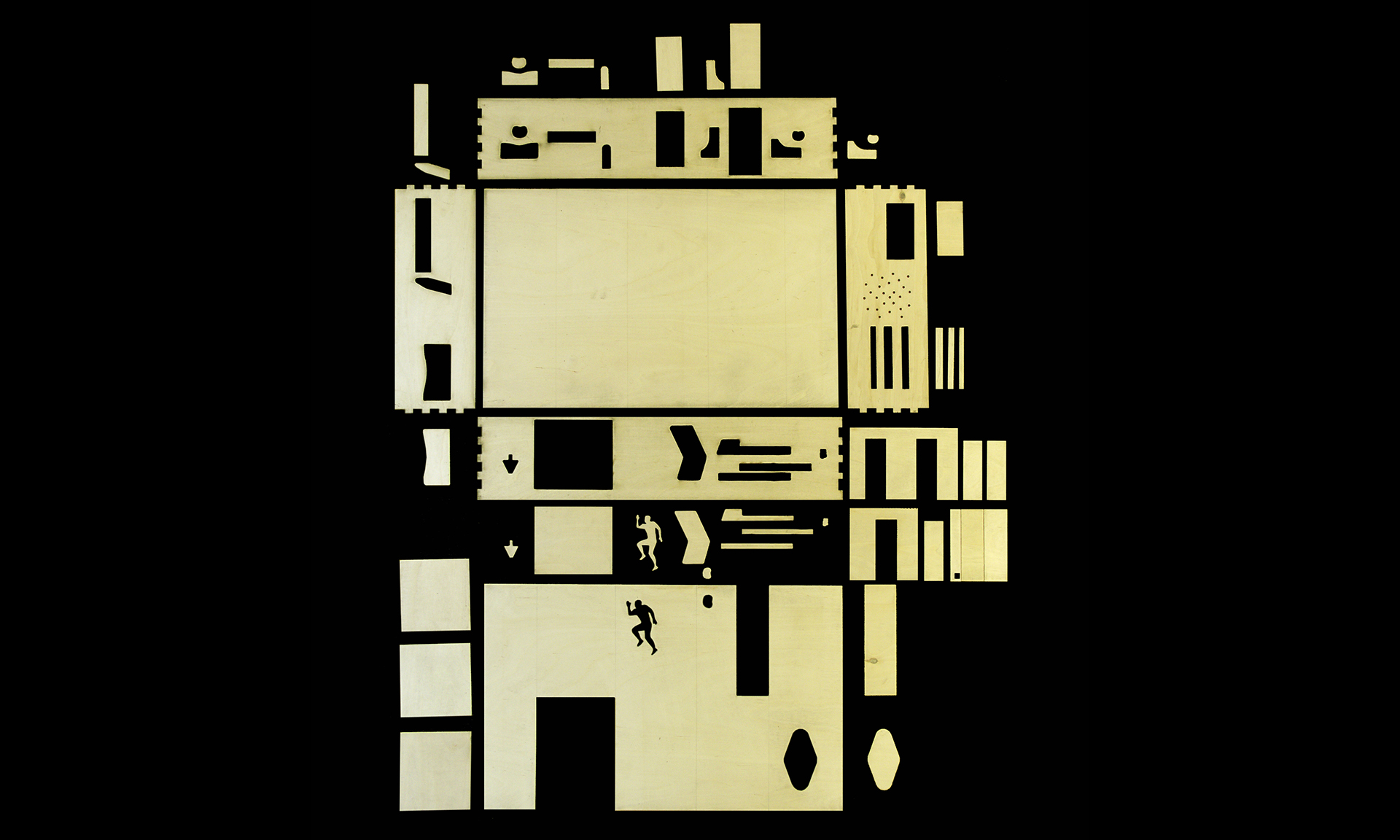

Another early project involving the use of CLT was the Naked House (2006). It was constructed in six days for an exhibition in Oslo entitled Industry, demonstrating the material’s potential for fast, prefabricated and modular high quality building. “It captured the imagination of many developers and architects.”

Skills

Almost twenty years later De Rijke observes that people are beginning to expect and even demand that buildings are made of wood. Timber, the oldest building material in the world, has become on trend. “Skills have been passed on in some places, but in many countries they were forgotten about in the wake of the industrial revolution.” The present generation of students holds the keys to a more resilient future, he says. Wood as a resource for urban development is one of them.

Many students here are already interested in bio-based design and are eager to learn more.

“They need to be taught how to conceive, design and detail timber architecture. If wood is applied only as a substitute material, buildings may not perform properly.” Wooden structures, he explains, can get wet but have to dry out. In a damp climate, how do you take regular rain into account? “By creating overhangs, following the example of the temples at Nara, Japan. These cleverly jointed and well-ventilated timber structures have lasted for more than a thousand years.”

Less mass

Almost all new timber structures are hybrid structures, says De Rijke, combining timber with steel connectors, concrete foundations and glass. “In Delft, I’d like to explore with master’s students and PhD-candidates how to increase the utility of bio-based materials, striving for all-timber structures with less mass.” This will involve experimenting with weight-strength ratios and jointing techniques. “Steel is incredibly strong but very heavy, so is concrete. Steel and concrete buildings consequently require significant foundations. These are invariably concrete.” What if structures were much lighter? “Could we then also switch from concrete to bio-based foundations? And are we able to increase the performance of wood in tension by innovating or rediscovering jointing techniques so that longer spans may be achieved?”

BioBuild Lab

De Rijke also intends to assess thermal qualities of bio-based materials in relation to wood. “How do we make buildings from natural materials that remain cool on the inside while hot on the outside? It’s an increasingly pressing question and I’ve seen examples that may inspire new designs.” Students and postgraduate researchers will be tackling such issues in a designated BioBuild lab, focused on hands-on experience and testing of prototypes of scale structures as well as components. “As a part-time professor I will be involved with lab activities but also act as a kind of consultant to various graduation studios.”

Expecting to spend on average two days a week in Delft, he says he is keen to establish a base in the Netherlands and improve his Dutch. “I own a 62 meter long Dutch barge, a Kempenaar, that used to ship cargo on the Rhine. I imagined having a floating studio in London, but dRMM grew too large. So now it might serve as a satellite studio and a facility for architecture postgrads wanting to conduct research. It’s a serious plan, I just need to find a mooring.”

More information

Alex de Rijke is Professor Timber Architecture in the AE&T department of the Faculty of Architecture and the Built Environment at the TU Delft. He has his own practice dRMM Studio.

See his professor page here.

Thanks in part to the support of PME and Achmea Real Estate, a team of scientists, including a prospective professor, at TU Delft's A+BE Faculty will be able to start honing their knowledge and expertise of designing buildings made from wood and other biobased materials. The Biobased Design Team will study these materials and teach students about the potential applications. The goal is to drive the transition to biobased construction and reduce carbon emissions throughout the design and build chain.