By Heather Montague

Unexpected events in the cockpit can provoke a startle and surprise response in pilots, sometimes resulting in fatal crashes. So, can pilots be given more effective tools to respond to these situations? Dr Annemarie Landman set out to investigate this topic in her recent doctoral thesis.

Better training needed for crisis management

Statistics show loss of control in-flight is the leading category of fatal accidents in commercial aviation. After several recent incidents, investigators concluded that startle and surprise can have a significant impact on a pilot’s response to unexpected events. Aviation authorities recognise that preparing pilots for situations like this requires specific crisis management skills.

Since last year, airlines and simulator training companies in Europe are required to incorporate startle and surprise training in their curriculum. While the need for more effective training is clear, how to design appropriate methods is less clear as there is insufficient data on the topic of how pilots respond to startle and surprise. Landman’s research focused on finding more effective training methods. “What does it really mean if you say that someone is startled or surprised,” said Landman. “And can you use that understanding of the problem to point towards certain better ways of training?”

Focusing research on surprise and stress

In common language, the words startle and surprise are often used interchangeably. But in scientific literature, Landman says that the two terms have very different causes and effects. A startle response is actually a very narrow concept. “It’s really this reflex, a sudden flinch. It’s very fast and it can also quickly subside again,” she said. “It’s a response to something that’s really intense, like a loud noise or a sudden movement, or something that is quite quickly determined as threatening.”

In contrast, Landman wrote that the concept of surprise is a slower emotional and cognitive response to unexpected events that are difficult to explain. “It’s much deeper, not just a reflex,” she said. “It’s really how you think about the world, what are your assumptions, what is your understanding of it, what logic are you using.”

During her research, Landman arrived at the conclusion that the combination of surprise and the associated stress was more relevant to crisis management than the startle response. “People often use the word startle to also mean surprise, but that has led to a lot of confusion because then people were looking at the reflex response and saying that must be the cause of accidents. But I don’t think any plane has ever crashed due to a flinch response. It’s what happens after that, being highly stressed and having to solve this mismatch between what you see and what you expect.”

A conceptual model of behaviours and frames

In order to gain a better understanding of the startle and surprise response, Landman created a conceptual model. It first considers that a person perceives and interprets stimuli which then leads them to assess the situation. This is followed by the selection and execution of an action, which may give new feedback. The model also uses frames to explain the causes and effects of surprise. A frame, as defined in the thesis, is an explanatory structure such as a scheme or model, which links perceived individual data points together and gives them meaning. The previously mentioned perception, interpretation and actions are strongly dependent on the activated frame. So, when there is a mismatch between the incoming information and the frame, the person needs to make sense out of the situation. This eventually leads to reframing (changing the frame), after which a new understanding is reached.

New information can cause a complete change in perspective, said Landman. “You encounter a piece of information that doesn’t make sense with your understanding of the world. You want to go to where everything makes sense so that you have a grip on things, but it takes effort to get there. And if you’re stressed, that process of getting there may be blocked. In that case, you remain in this situation where everything is chaos. Without having the correct frame, you may not be able to interpret information correctly anymore.”

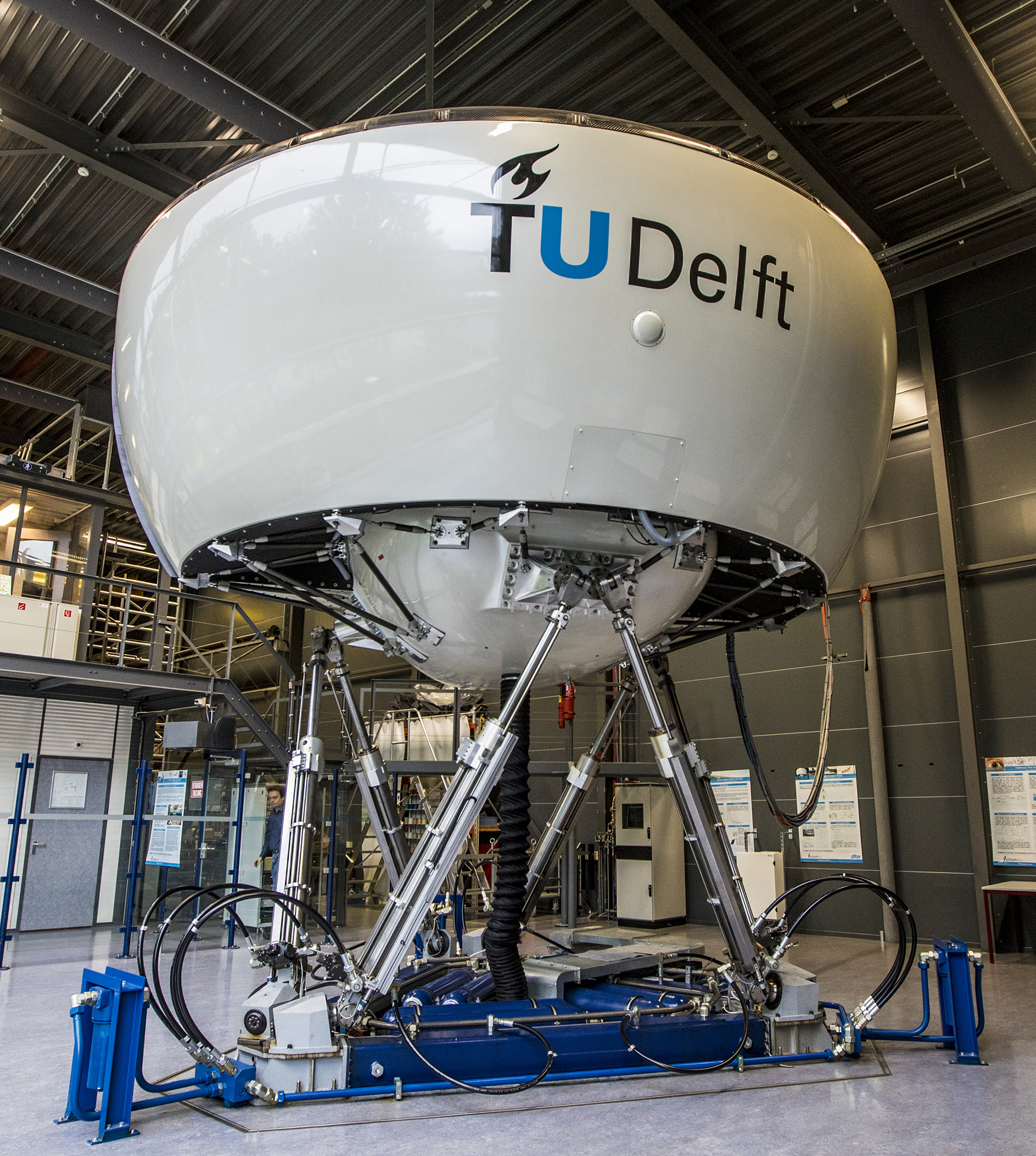

Experimenting in the simulator

Landman conducted several experiments with a simulator to better understand the effects of fear and surprise in the cockpit. For example, to test the surprise effect, she asked a group of pilots to perform the same tasks under conditions of surprise and anticipation. The results confirmed that procedures are indeed much more difficult to execute correctly when surprised.

The simulator experiments also looked at the effectiveness of potential training interventions. The first of these investigated the possible advantage of variable and unpredictable training scenarios. While one group of pilots practised responses to varied and unexpected circumstances, a control group practised the same responses under constant, orderly and known circumstances. The outcome of this experiment confirmed that pilot training designs are more effective and support the practise of reframing when they include varied and unpredictable circumstances. Landman also noted that even in the safe environment of a flight simulator, it is possible to train more effectively to deal with startle and surprise.

Lessons learned

Although her thesis is completed, Landman is clear that the research on startle and surprise is not. “It’s nice to clear your mind and think about something else at the end of your thesis. There’s probably still plenty to learn on this topic, but I kind of formulated my opinion and now I can let other people take over.”

As for what Landman takes away from this project she said: “Your frame, your mental model or assumptions really determine what you see. Not only in these perceptual tasks, but I would say in life in general. We have a certain resistance against changing our assumptions because we don’t like it. It’s chaotic and we want to keep control, maintain our grip on the situation. It’s interesting to reflect on whether a different perspective is really just nonsense, or whether it only seems that way because you are resisting a change of frames.”