Who decides what the heritage value of a neighbourhood is? If it was up to Lidwine Spoormans, that would include not only heritage experts, but anyone who lives, works, or runs a business there. For her thesis, Spoormans examined houses built between 1965-1985, and asked what makes them valuable. “Opinions differ; residents, visitors, municipalities and architects all have a different perspective.”

“We often think of heritage as protected heritage, such as national monuments. But I think everything we have inherited from previous generations has a certain value,” says Lidwine Spoormans. In her thesis Everyday Heritage: Identifying attributes of 1965-1985 residential neighbourhoods by involved stakeholders, she examined Dutch housing environments built between 1965 and 1985. “If we do not see the value of these neighbourhoods today, that is due to our own limitations.” For her thesis, Spoormans wanted to know which attributes of these neighbourhoods were considered valuable, and by whom. Because, she says, if we do not identify what is the heritage significance of these neighbourhoods, it may diminish or even be lost. “The built environment will undergo major changes in the coming years. Houses will have to be adapted to meet sustainability targets, while densification and climate adaptation measures will put additional pressure on neighbourhoods dating from the 1970s and 1980s. We may end up losing many of their typical elements,” she warns. Of course, exactly what constitutes heritage significance is up for argument. “Traditionally, architectural historians have often based their judgments on aesthetic and historical qualities, for example whether a building is old, unique or intact,” continues Spoormans. “But I wanted to include a broader group of stakeholders, and ask them what they thought was important.”

Livability and variety

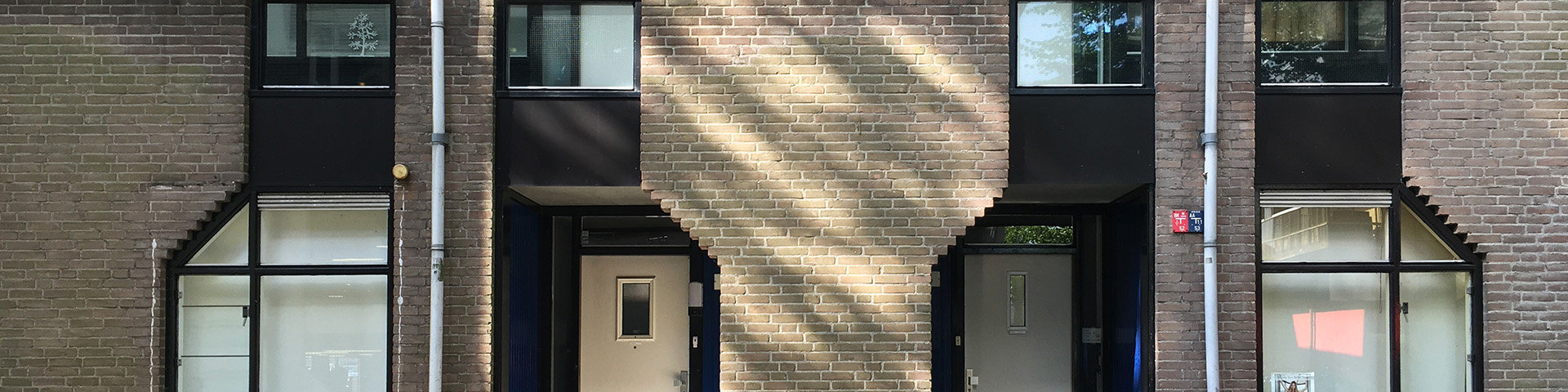

For her thesis, Spoormans chose two case studies: the neighbourhoods of Almere Haven and Amsterdam Zuidoost. These neighbourhoods are very representative for the country and contain many typical 1970s and 1980s features, such as courtyards, pitched roofs and alcoves. For the survey, residents, local professionals, and municipal and housing corporation staff were shown a picture of a house or street, for example, and given variants of open-ended questions that boiled down to: ‘What do you think is valuable?’ “The respondents were given complete freedom to decide for themselves what they thought was important,” says Spoormans. “This produced a wide variety of both tangible and intangible attributes. They described typical features of that period, such as the use of bricks and the neighbourhood structure with courtyards, also known as the ‘new triteness’. But the mix of single-family homes and apartments, owner-occupied and rental homes, and dwellings and shops in one area was also much appreciated.” More generic attributes also emerged that are not specific for the construction period. “People like to see a lot of greenery in a neighbourhood, but that is probably not unique to that period. Social cohesion and events such as neighbourhood parties were also mentioned. And many residents appreciate that their homes are ‘their own’; people like having a place of their own, with their own personal memories. With these attributes, heritage significance overlap the quality of the living environment in general.”

Many people are happy to live and work in these neighbourhoods.

Lidwine Spoormans

Emancipation of heritage

With her thesis, Spoormans has tried to bridge the gap between protected heritage and ‘everyday’ heritage. “The Environment and Planning Act will be introduced next year. Under this Act, governments are required to draw up an ‘Environmental Vision’ that describes their primary planning responsibilities and the qualities in their area. This means knowledge will be required not only about old neighbourhoods and listed buildings, but also about other areas that do not have a heritage status. That will require broad participation. I hope my research will encourage people to take a new, unbiased look at everyday heritage. Instead of always striving for newer and ‘better’, it is important to look more closely at what heritage we already have and what its qualities are. This is all the more important in the context of sustainability and circularity: the most sustainable option is often not to demolish and rebuild, but rather to leave a building standing. But it is also important for emancipation: many professionals tend to look down on 1970s and 1980s architecture, but 30% of the Netherlands was built in that period, and many people are happy to live and work in these neighbourhoods.”

Published: December 2023

More information

On 13 December, Lidwine Spoormans defends her thesis 'Everyday Heritage: Identifying attributes of 1965-1985 residential neighbourhoods by involved stakeholders’. The thesis can be downloaded here.