Marlies Goorden

What exactly do you do at the cutting edge of technology and healthcare?

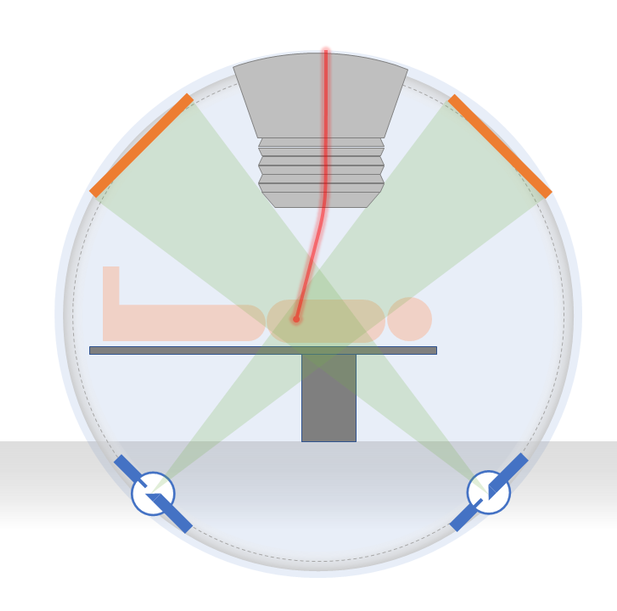

Proton therapy is a high-tech therapy for treating cancer. The protons are accelerated to more than half the speed of light in a large installation and aimed very precisely at the tumour. But if you are just a few millimeters off-target, the treatment is substantially less effective. That is why we are using additional technology to ensure maximum precision. We do this, for example, by taking a CT scan of the patient immediately before they receive radiotherapy and by adjusting the treatment plan accordingly, if necessary.

My health mentor is developing new hardware - the detectors - that allow you to extract as much information as possible from the CT scan, with the amount of radiation directed at the patient being kept to a minimum. I myself have extensive experience in developing algorithms, models, and geometries for all kinds of medical imaging. In the past, I used this knowledge mainly for improved diagnostics, and I am now doing the same for therapy. My goal is to reconstruct the patient's geometry, as shown in the scans, as precisely as possible, and to come up with suggestions to further adapt the hardware for even better imaging. Therefore we complement each other very well.

It’s worth noting in this context that the Holland Protonentherapiecentrum (HollandPTC) is located on the TU Delft Campus. This ensures very short lines of communication with both the medical staff - the radiotherapists, clinical physicists, and lab technicians - and the equipment supplier. You run into each other at the coffee machine, so to speak. This results in rapid and relevant developments that can be quickly adopted by the clinic. I really like the fact that my research is so directly applicable.

What is your impression of the medical world?

It’s great fun and highly motivating to work with all these people from different backgrounds. What I have noticed is that it is difficult to actually get new technology into the clinic. That is certainly not due to any lack of interest on the part of healthcare specialists, but is more the consequence of all the rules governing the medical field. This is not something you can just force, as a technician: it requires large projects on which you work with people from the medical field.

In the process, each of the parties is strengthened by the others. Clinicians do not automatically accept that something is better just because a technician says it is. And that’s just as well, because what is better in theory does not necessarily translate into an improvement in clinical practice. You really have to convince them.

Image: EEN SPECIALE CT SCANNER INGEBOUWD IN DE PROTONENTHERAPIE GANTRY (DE CONSTRUCTIE WAARUIT DE PROTONEN OP DE PATIËNT WORDEN AFGEVUURD) KAN WORDEN GEBRUIKT OM NET VOOR OF ZELFS TIJDENS PROTONENTHERAPIE DE PATIËNT TE SCANNEN.

CREDITS: DAVID LEIBOLD

Do you have a top tip for engineers who work in the medical field, or who would like to do so?

As well as taking a long-term approach, collaborating is also very important, so take advantage of the networking meetings TU Delft has to offer. Medical Delta, the Convergence with Erasmus MC, the Delft Health Initiative. Get out there and make sure you know people from both sides of the cutting edge.