How sustainable are smart devices?

You might think that smart devices – something that can connect to the internet or another device – would be more sustainable. After all, if the lights and the thermostat only turn on when a person is present, they should use less energy. ‘But’ says Emilia Ingemarsdotter, ‘every technology has a hype phase’. For her PhD research, she wanted to look beyond the hype and critically examine the role internet-enabled devices play in the circular economy.

At the start of her PhD-research, Ingemarsdotter, who is originally from Sweden, quickly discovered there was not much academic research into what role the Internet of Things – the network of these devices – would play in sustainability and specifically in the system of minimising waste and continually reusing resources in the economy, known as the circular economy. Her Ph.D. thesis references more than 40 case studies, ranging from the installation of supermarket lighting systems to the manufacture of forklifts.

‘There were a lot of people and publications talking about what was possible with the Internet of Things in circular strategies but very little on implementation, she says. Ingemarsdotter wanted to look at what companies were actually doing and the research in her thesis focused on the commercial use of internet-enabled devices.

Rather than using papers in academic journals, she turned to other sources. ‘I used a lot of grey reports,’ she says, finding sources in white papers, annual reports, and other sources outside of academic publishing.

Costs and privacy

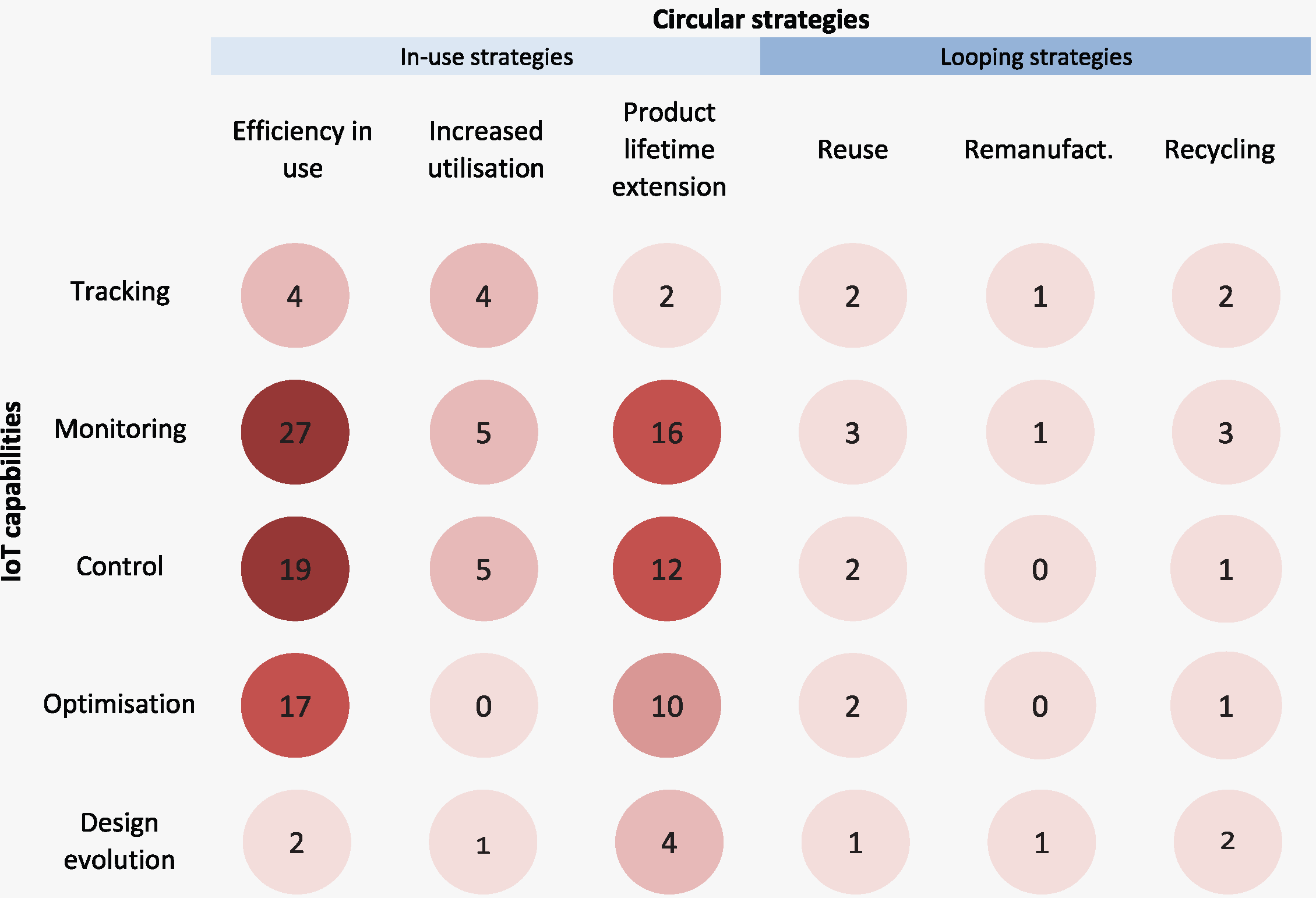

With little of a foundation to build on, Ingemarsdotter started by creating a categorisation framework for how the Internet of Things was supporting circular strategies in practice. ‘The idea needed a language,’ she says. In the end, she came up with five: tracking, monitoring, control, optimisation, and design evolution. ‘The categorization allows for easy mapping of diverse cases,’ she writes in her thesis.

In her thesis research, she discovered that the use of internet-enabled devices in a sustainable way converges on two topics: optimising energy and maintenance. ‘It’s not that surprising,’ Ingemarsdotter says. For businesses, energy use is a major cost factor, so companies are willing to invest in technology that clearly reduces that expense. Maintenance is related to uptime, how often systems are functioning correctly, another expense that is easy to quantify and demonstrate the benefit of, according to Ingemarsdotter.

‘Ultimately, it’s difficult to get circular business models in place,’ she says. Companies want to know there will be a benefit to their bottom line before investing in new technology.

Beyond costs, there are other concerns about internet-devices as well. For consumers, these concerns might cover privacy or whether they will be able to unlock their front door or turn on the heating if their internet goes down. Ingemarsdotter points out there is another issue as well: being less green by replacing your old devices with new ones.

All the moving parts

Ingemarsdotter herself lives a fairly minimalistic lifestyle. The only smart device she owns, other than her laptop and phone, is a smartwatch.

‘The impact of things like electronic waste is not always critically discussed,’ she says. One of the case studies in her thesis looks at monitoring heavy-duty truck tires in Sweden. If tire manufacturers incorporated a device that monitored tire wear and pressure, the usage of the tires could be better optimised. Properly pressured tires, for example, are more fuel-efficient. However, before incorporating such a device, you would need to consider the added environmental impact of producing the electronic components. “I want to see a holistic viewpoint,” she says.

She is now working on a research project looking at safety in repairability. One big component of the circular economy is making consumer goods, like vacuum cleaners or blenders, repairable. But there are very real safety concerns about having the average person tear open their refrigerator to replace a part.

Going forward, Ingemarsdotter wants to continue to focus on this holistic view. ‘There are a lot of different ways to understand the sustainability of a product or system,’ she says. And she wants to continue working with numbers, something she is always known she enjoys. ‘I like quantifying things.’