Is the robe in that painting velvet or satin?

Staring at one of the richly drawn paintings in Amsterdam’s famous Rijksmuseum, you might recognise that the robe worn by the subject of the painting is made of velvet and the cup on the table is made of silver. Your eyes only see swirls of paint but your brain understands what the artist was depicting. As part of his thesis research, Mitchell van Zuijlen wanted to understand how this is possible.

Before starting his PhD, van Zuijlen studied psychology at Utrecht University. To many, the field often focuses on the negative experiences that people have with their brains, such as diseases or mental health problems. But van Zuijlen is more interested in typical human experiences. “Humans can do very complicated tasks extremely easily, often from birth,” he says. It is these aspects of the brain that he finds fascinating.

His research was funded as part of a VIDI grant from The Dutch Research Council (NWO). The project sought to better understand how artists depict material properties in paintings. When you look at a still life from a Dutch Golden Age painter like Rembrandt, how does your brain see the objects in that painting as a cup made of silver or a robe made of velvet, rather than simply seeing blobs of paint?

“Human beings can look at an object and understand a lot of its material properties: how heavy it is, what the texture is like, etc.,” says van Zuijlen. Scientists don’t totally understand how the brain processes this information, but artists like Rembrandt clearly understood how to relay that information through their work. The fact that painters can do something researchers can’t explain highlights van Zuijlen’s approach to his work. He stresses it's important for researchers to work in multidisciplinary teams. “Otherwise you end up reinventing the wheel.”

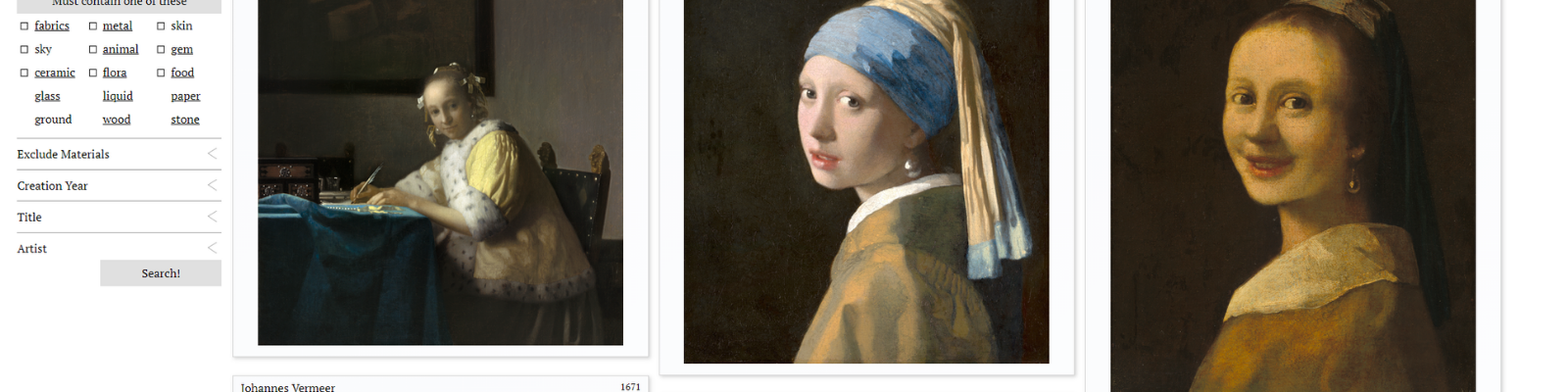

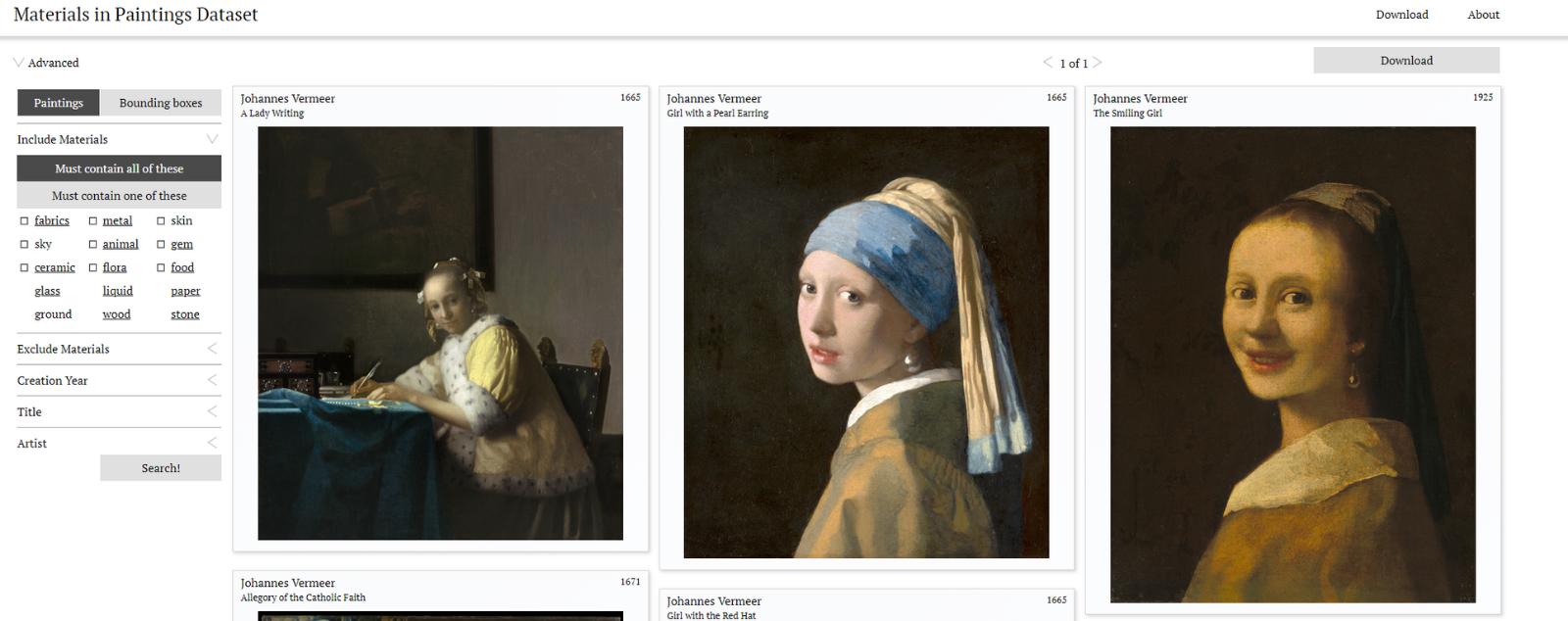

Van Zuijlen’s own research contribution was less about answering the specific question about brain function and more about giving other researchers the opportunities to do so. He ultimately created the Materials in Paintings Dataset, a repository of 20,000 paintings collected from museums all around the world, including Amsterdam’s Rijksmuseum, the Metropolitan Museum of Art in New York City, and The Prado Museum in Madrid.

When van Zuijlen first set out to compile his dataset four years ago, the number of museums providing high-resolution photos of their collections online was small. The Rijksmuseum was a forerunner. It first made high-quality photos, taken in studio-settings by professional photographers, of some 125,000 objects in its collection available in 2013. Today, all of the more than 700,000 works of art can be seen on the museum’s website. “Once the big museums like the Rijksmuseum and the Metropolitan Museum of Art began to digitise, other museums followed suit,” says van Zuijlen. He ultimately catalogued works from ten museums into his dataset.

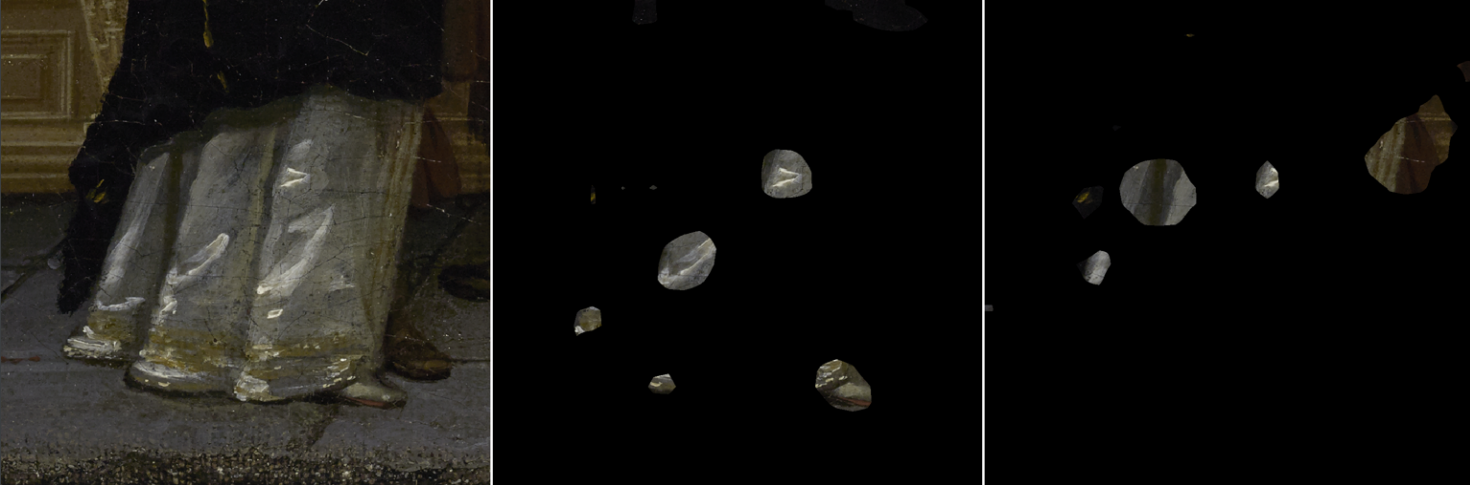

Merely having the images, however, wasn’t very useful. “We needed to know what was in those images, specifically, what materials were depicted and what properties those materials had,” van Zuijlen says. So he turned to an online platform that allows businesses and researchers to crowdsource information for digital tasks. In van Zuijlen’s case, he used the platform to get thousands of people to look at the paintings in his database and tell him what objects were shown in those paintings. Then he crowdsourced what materials the objects were made out of and a number of qualities about them. For example, whether an object appeared shiny or soft. He got millions of responses.

With this information available, other researchers can study what makes objects in a painting appear realistic. Van Zuijlen’s colleague, Dr. Francesca Di Cicco was working on just such a project and lamented that her life would have been much easier had his dataset been complete at the time.

Van Zuijlen has now accepted a position as a researcher at Kyoto University in Japan where he will continue to work on better understanding how humans perceive the world. He’s now moving on from static images to how moving objects are depicted and how materials and motion interact.

Mitchell van Zuijlen

Maarten Wijntjes

- +31 15 27 81835

- m.w.a.wijntjes@tudelft.nl

- Github

-

Room C-3-260

Present on: Mon-Tue-Thu-Fri