‘You first have to understand why people are equal before you can understand why they’re different.’

Paul Hekkert conducted research for years on the underlying principles of aesthetics and experience. As a ‘scientific figurehead’, these past two years he has mainly focused on creating the knowledge and innovation agenda for the Creative Industry top sector.

Paul Hekkert became interested in dance and aesthetics while studying human movement sciences at the VU Amsterdam. With temporary co-funding from the Ministry of Education, Culture and Science, he managed to set up a PhD study on how art and cultural grants were awarded in The Netherlands in the 1990s: a committee of ‘wise men’ who determined behind closed doors who should and should not be given a grant. Is that a legitimate way of distributing public funds?

‘In those days, only high-quality artists received funding. Less talented artists were discouraged to persuade them to go and do something else,’ Hekkert says. ‘But to justify that the government had to be absolutely sure that they had a reliable way of assessing quality. There are no objective criteria, so you’re forced to rely on “peer review”, a committee of experts in other words. I examined how to best accomplish that, and how people come to assess beauty. The world of art didn’t want to know about it at all. It had no interest in whether something is scientifically objectifiable. That only stood to undermine their position.’

Hekkert’s work did strike a chord at the faculty of IDE, however, and he was given the opportunity to finish his dissertation on the indicators of aesthetics. He switched from the visual arts to design. ‘Everyone in the world of design was extremely interested in this. After all, a designer has to be able to explain to his customers and clients why something is visually appealing. He will want to have certain principles at his disposal, a kind of “vernacular”. I want to give designers this vernacular. I delved pretty deeply into the human psyche in search of it.’

A lot of designers are obsessed by the many differences between people, for example what they consider beautiful, Hekkert says. ‘These differences exist, but there are similarities within these differences too. You first have to understand how people are the same before you can understand why and when differences arise. I’m less interested in what person A likes and what person B likes, and much more interested in why we find something beautiful at all. Why do we attribute character traits to products, for example? What are the underlying principles there? To figure that out, you need to return to the roots of human existence, evolution in other words.’

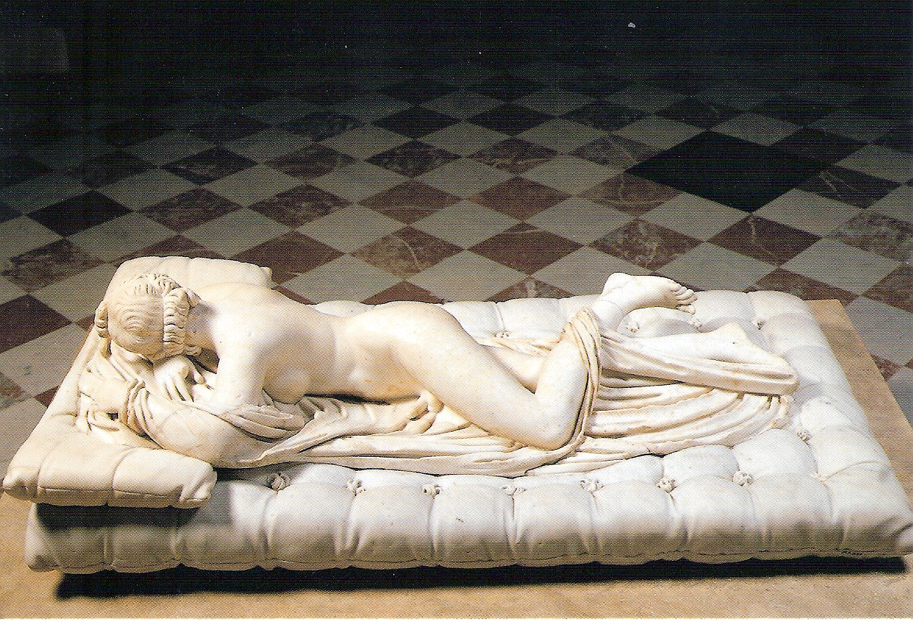

‘Essentially what people find beautiful, attractive or tasteful are the things that help us survive,’ Hekkert explains. ‘Two things in particular are key to survival. First, safety and security. A cave provides security, but anyone sitting in a cave all day long will never go out to gather food and learn new things. To survive people therefore also need to explore and be challenged. That’s a dilemma, because these two principles – being safe and being challenged – are opposites of each other. Beauty arises when we succeed in reconciling these two seemingly incompatible dimensions after all. I often use the statues of the seventeenth-century Italian artist Bernini as an example. Most of these sculptures exude a kind of softness, security and warmth, but at the same time they’re made of rock-hard, cold and white marble. Two contrasting dimensions, that’s precisely where the beauty comes from.’

Designers can play with a product at different levels to reconcile these two principles. Hekkert studied this for a long time at the IDE faculty, with Dirk Snelders for example. ‘At the time we showed that the product people found most appealing was always the one that was both the most familiar and the most original. Of course, what people find familiar and what they find new will differ according to culture, time and place. It depends on what you have seen previously, for example. That explains why Africans and Asians consider different things to be beautiful than we in West. But that doesn’t detract from the universal validity of the principle.’

‘If designers would like to have meaningful discussions about the choices they make, then it’s important that they understand these kinds of universal principles and that they have a vernacular they can use to talk about it. So they can go beyond the superficial differences between people. But design research is increasingly becoming applied design, and that concerns me. More and more, researchers are making practical designs themselves. That’s partly the consequence of the popular notion of “research through design”. As a result, we’re losing sight of our knowledge base at a deeper level. I have therefore tried to translate into my work, as a scientific figurehead in the Creative Industry Top Sector, the question of what kind of knowledge designers will need in the future. You can view the recently completed 2018-2021 knowledge and innovation agenda, a recommendation about how we think that available public funds should be used, as an attempt to put the knowledge base back on the agenda.’