Bubble Games: can we design for empathy?

Building a better society is no solo endeavour. It needs people to join forces and tackle problems together. But this can only happen if there is a foundation of trust and understanding. In an increasingly polarised world, a group of Dutch designers, including TU Delft’s Froukje Sleeswijk Visser, asked whether it possible to create this strong foundation? Can we design for empathy? And what role might digital technologies such as Virtual Reality play in helping us understand what it means to walk in one another’s shoes? Welcome to Bubble Games…

Picture this. A drone-mounted camera hovers towards a new build area on the outskirts of the Dutch city of Eindhoven. Beyond the green fields and water ways lies a cluster of neat red brick flats which make up the neighbourhood of Meerhoven. The camera cuts to street level, panning along the shopping street. It’s clean and calm. An occasional bike cycles whizzes past: a typical Dutch neighbourhood scene. Or so it seems…

A narrator informs you that beneath the harmonious surface, runs an undercurrent of tension. Irritations regularly reach boiling point around the shopping centre with daily confrontations between the neighbourhood’s youths and other residents.

At this point you might shrug your shoulders and write off Meerhoven as another one of those problem areas: somebody else’s problem but you don’t get off the hook that easily because this isn’t any old documentary. This is a virtual reality film, created by the Bubble Games consortium and you’re about to experience how it feels to live somebody else’s life

Representing the “youths” and the “other residents” are Bram (19), Andy (19), Tjitske (44) and Pierre (62). These four individuals were recruited as representatives of their neighbourhood for what they were told was a research project on Virtual Reality and empathy.

The resulting 3D film, “As if I knew you…” works on multiple levels. Firstly, it allows the viewer to feel the emotional and physical effects of VR (VR), which Bram, Andy, Tjitske and Pierre experienced as part of the project. For example, when you find yourself in Tjistke’s daughter’s bedroom, as she tidies her daughters pyjamas and duvet, all the while telling you about their life in the neighbourhood. The result is an uncanny sense of intimacy. The same when you enter and take a look round the pristine white living room of Pierre, a man who wants to focus on his hobby of quietly creating music. As you can sense, he’s a considerate sort of man. He plays electric guitar with headphones in and would naturally prefer not to be disturbed by a ruckus when he opens his windows in summer. Meanwhile when you arrive at the picnic table on the edge of Meerhoven, where Andy and Bram huddle smoking roll-ups and chatting, the perspectives of these two young men, who crave respect and a space where they won’t be negatively judged, become infinitely more relatable.

After donning the VR goggles and immersing themselves in the lives of their neighbours, all four of participants professed to identifying more strongly with each other due to the exposure to the perspective of another. “The VR video, it’s as if you’re actually stepping into their world, sitting on their sofa...” comments Tjistke. But as the film goes on to document, the project’s ambitions go beyond experimenting with the out-of-body experience offered by VR. The Bubble Games Consortium, funded by CLICKNL, brings together TU Delft’s Faculty of Industrial Design Engineering with Fabrique, the City of Eindhoven, Fontys Hogescholen, VR Gorilla, Fonkeling, Liesbeth Bonekamp and ASML. Together they set out to explore the wider question of whether design interventions can combat polarisation before it takes root, ultimately building greater social cohesion.

That’s why some weeks after the VR viewing, the project participants are reunited in a co-design workshop, facilitated by Fabrique’s innovation strategist and IDE alumnus, Jeroen van Erp. Presented with a scale model of the neighbourhood, they are challenged to consider each other’s experiences of the neighbourhood. What ideas do they have for improving their own community? What potential do they see in the spaces? The film concludes with Jeroen van Erp introducing Bram, Pierre and Tjitske to representatives from the municipality. They discuss their ideas for improvements, including using a competition as a means encouraging locals to come up with ideas for better places where young people can hang out.

The ripple effect of this project, which has been nominated for the Hein Roethofprijs aimed at increasing social safety, has the potential to be significant. But what can the design intervention itself – which includes the process of making the documentary, the VR viewing and the co-creation workshop to discuss the scale model of the neighbourhood - tell us about the possibility and scalability of designing for empathy? Can we, through good design, increase the innate ability of people to understand one another? And is it possible to amplify this potential effect, taking empathy beyond a one-on-one relationship, to influence how we see different groups in society?

“Our theory from the get go was that the empathy of the residents with each other would be increased by participating in this small project. The very fact that they were prepared to take part was already indicative of their openness to alternative perspectives,” explains Associate Professor Froukje Sleeswijk Visser, a young researcher who herself features in the documentary, interviewing and observing the residents. “But the big questions for me as a design researcher were how we could measure that empathic effect and how their increase in empathy with the others occurs.”

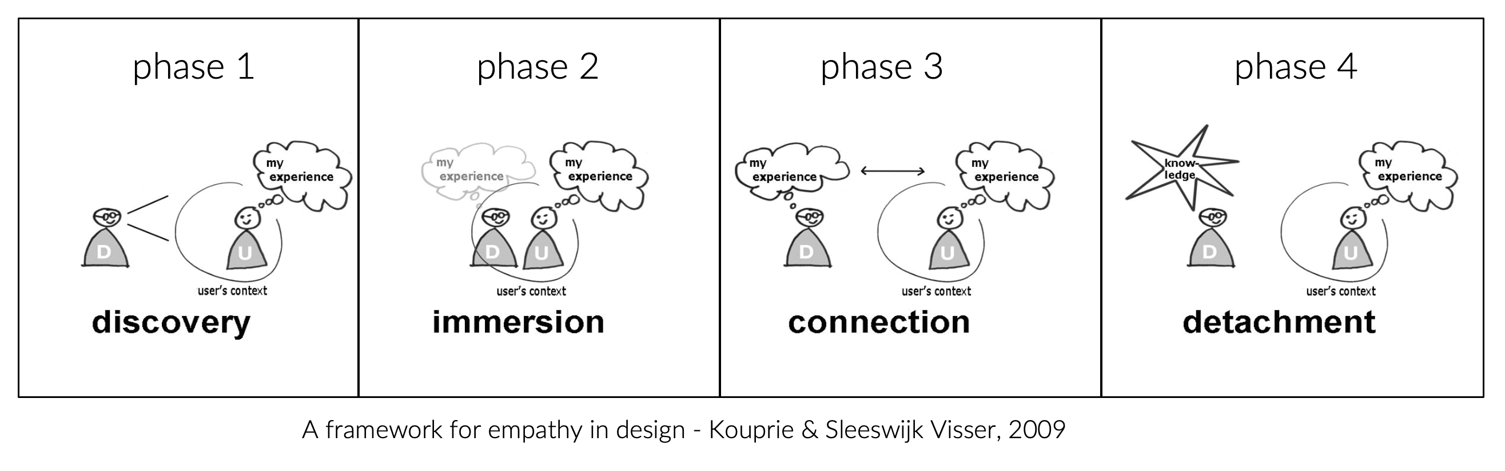

In approaching these questions, Sleeswijk Visser went back to a model she developed as a PhD candidate. Her “Framework for Empathy in Design” (2009) describes four stages of user-centered design: discovery – when your curiosity about another person is sparked, immersion – when you spend time in the context of another, connection – when you start to feel something about how it might be that person and detachment – when you step out of that context with the knowledge which will empower you to go on to design the product, service or system suited that particular user.

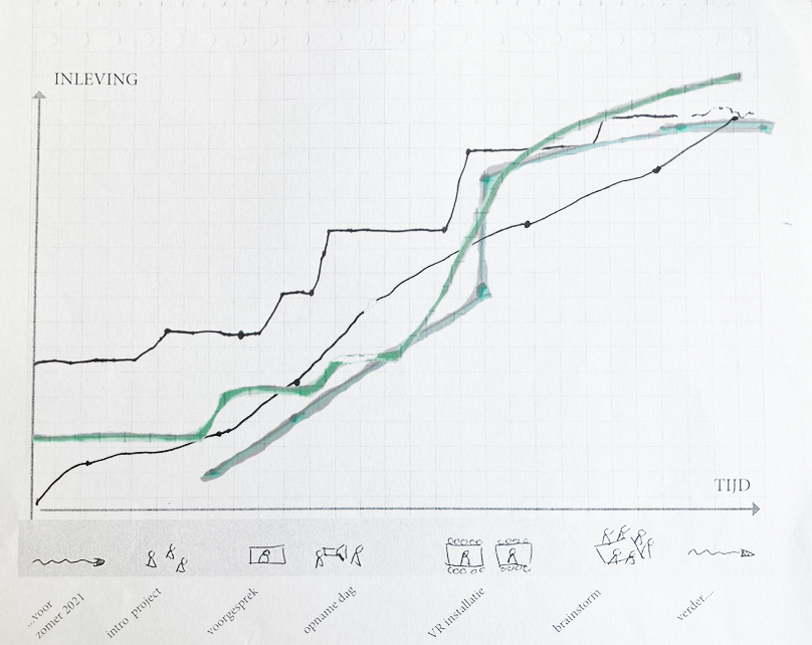

With this model as a point of reference, Associate Professor Sleeswijk Visser steered the Bubble Games project away from standard empathy questionnaires, typically used in clinical mental health settings, instead developing a more qualitative approach. Her holistic measurement method included interviews and researcher observations and researcher assessments of participant empathy level at key milestones. Empathy was broken down into four aspects, namely the willingness to participate in the project, the level of curiosity, the extent to which the perspective changed and the degree to which language use softened.

Plotted on a graph, the Bubble Games experiment shows an impressive upwards trend. The key phases of the design intervention (the initial interviews, VR viewings and the co-design workshop), which correlated with the immersion and connection phases in Sleeswijk Visser’s framework, helped increase (and sustain) levels of empathy over time.

And what does Sleeswijk Visser see as the specific role of VR in this? She explains that not only is it personal and intimate, like the scenes of Tjiske tidying her daughter’s bed, it surrounds you as a viewer and traps you. Short of removing the goggles, there is nothing that you can do but watch and feel the other’s perspective.

“Even though we usually think of empathy as something that happens in a one-on-one relationship” reflects Sleeswijk Visser, “it was surprising to observe how after the VR viewings, the participants didn’t just refer to the other individuals but to the groups that they represented. This might indicate that the design for empathy framework can have a larger application in helping combat polarisation.”

Froukje Sleeswijk Visser

- +31 (0)15 27 83537

- F.SleeswijkVisser@tudelft.nl

- Publications

-

Room B-2-140 StudioMingle

"Bringing the everyday life of people into design."